Asian dementia on the rise in Singapore

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

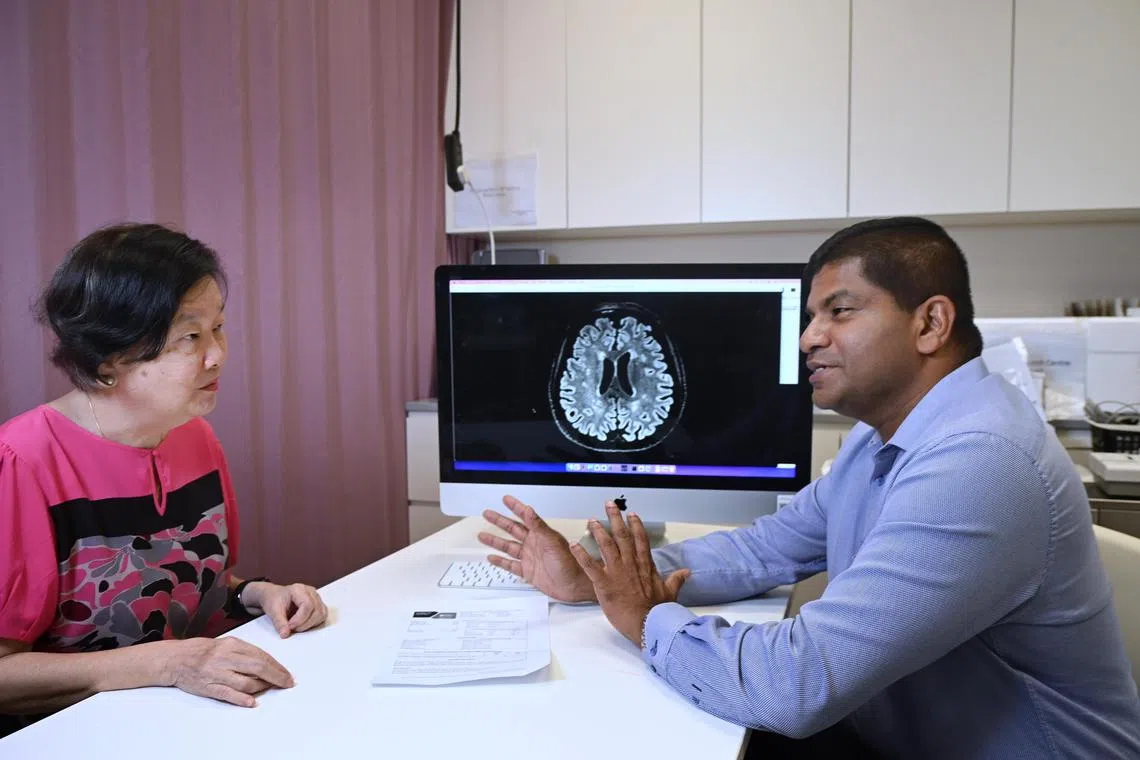

Professor Nagaendran Kandiah with research participant Connie Wong, whose MRI scans revealed white matter in her brain, indicating potential risk factors that may require medical attention.

ST PHOTO: DESMOND WEE

SINGAPORE – In an ongoing research study

This is the latest sobering data uncovered by a team of scientists at the Dementia Research Centre (Singapore) (DRCS), which was launched in April 2022 at the Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine at Nanyang Technological University, led by its director, Professor Nagaendran Kandiah.

MCI is a collection of symptoms that fall somewhere between age-related cognitive changes and abnormal mental decline that may stem from a serious illness of the brain such as Alzheimer’s disease.

Dementia is an irreversible brain disorder that interferes with one’s ability to go about daily activities, and refers to a range of dysfunctions such as severe memory loss, as well as mood and behavioural changes.

About one in 10 people aged 60 and above in Singapore has dementia, according to a 2015 study by the Institute of Mental Health.

In 2017, Singapore was classified as an “aged society”, and it is set to attain “super-aged” status in 2026. According to the United Nations, a country is super-aged when 21 per cent of its population are aged 65 and older.

By 2030, one in four here will be aged 65 and above, up from one in six currently.

Singapore’s average life expectancy in 2022, according to the Department of Statistics, was 80.7 years for men and 85.2 years for women.

For its primary Biocis study, abbreviated from Biomarker and Cognition Study, Singapore, DRCS is working with local hospitals and community partners such as Khoo Teck Puat Hospital and National University Hospital to recruit 2,000 participants with memory concerns to study “Asian dementia” at its prodromal, or earliest, stages.

Its aim: To detect diseases that cause dementia at the earliest possible stage through cutting-edge blood-based biomarkers and state-of-the-art neuroimaging tests such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to prevent and delay the development of dementia.

The Biocis study on the 2,000 participants is expected to conclude in 2027. Those who signed up voluntarily were aged from 30 to 95 and had expressed concerns with their memory and forgetfulness to their friends, family or social workers but had not sought medical attention prior to the study.

About 94 per cent of them were Singaporean. Ethnic Chinese participants comprised 90 per cent, with the remainder made up of Malays, Indians and other races to form a close representation of the Singapore population.

Prof Kandiah says this is a pivotal study in the more-than-100-year history of dementia studies worldwide, as this is the first time intensive studies are being conducted entirely on South-east Asians to draw up a more accurate picture of the unique biological factors of the Asian brain that causes dementia.

Out of the first 818 patients studied, 597 – or 72 per cent – had some form of cognitive impairment. Of this group, 389 had MCI, while the other 208 had subjective cognitive impairment, a form of self-reported memory decline.

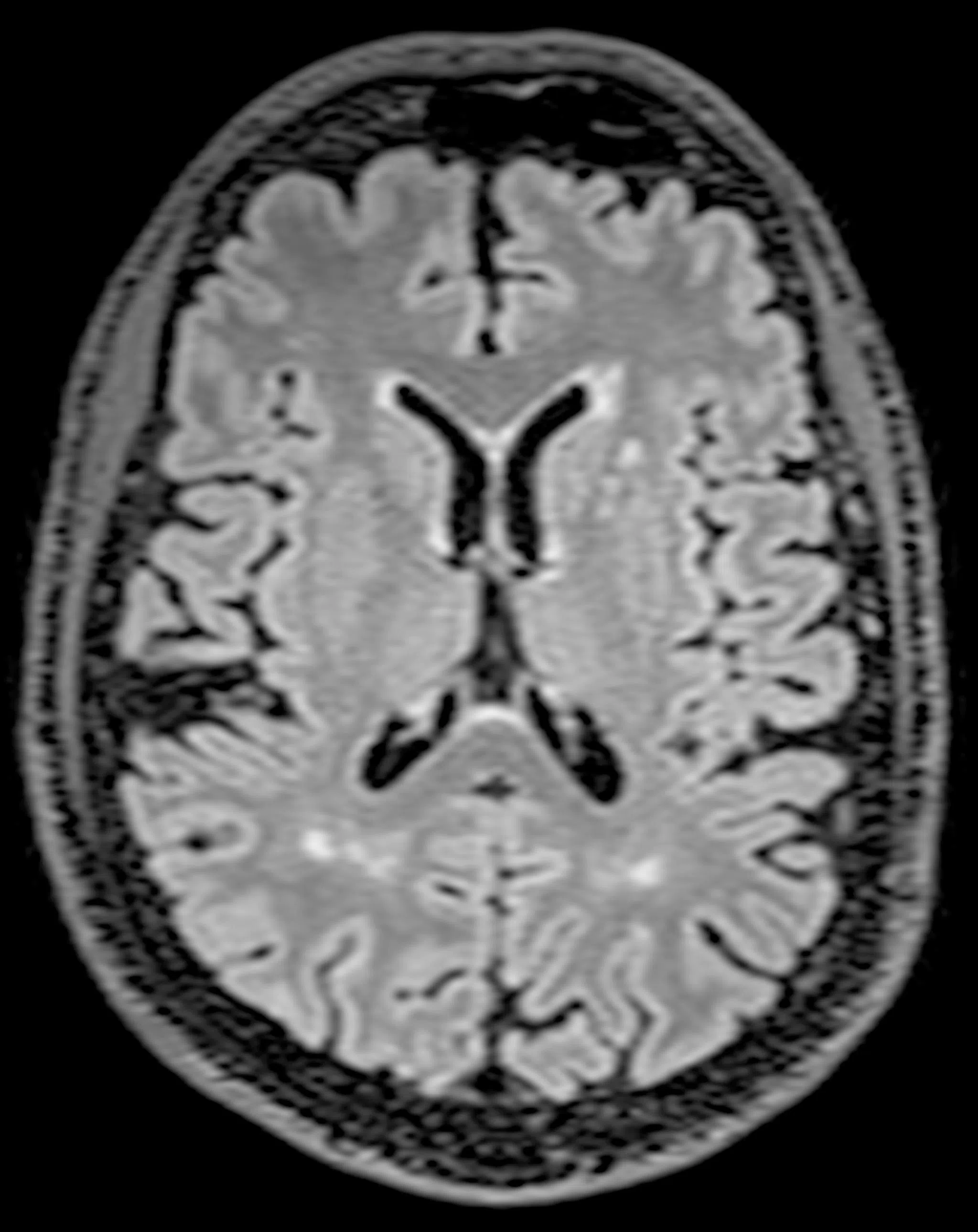

Preliminary findings, as well as emerging studies conducted in Asia, have found that Asian patients are three times more likely than Caucasians to suffer from silent strokes as a result of a condition of the narrowing of the small blood vessels which appear as lesions or “white matter hyperintensity” in brain scans.

The bad news? This is an early sign of increased risk of dementia. The somewhat good news? The prevalence of two elements usually associated with Alzheimer’s disease – the APOE4 gene and abnormal levels of amyloid-beta protein – is much lower in Asian patients, observes Prof Kandiah.

But in many global clinical trials, thus far conducted mainly on Caucasians, the APOE4 gene is typically included as a factor in testing for cerebral disease.

Research done by DRCS further showed that in Asians, small vessel disease results in more brain shrinkage among those who do not have the APOE4 gene, which calls for personalised strategies – “not cookie-cutter methods” – to manage Asian patients with dementia, says Prof Kandiah.

Another global risk for dementia is the “tau protein”, which one in three DRCS study participants were found to have in their brain, although in many of these cases, there was no evidence of any amyloid-beta protein.

“When you talk about Alzheimer’s disease, the main culprit is the amyloid-beta protein,” says Prof Kandiah, who was previously senior consultant and Dementia Programme Director at National Neuroscience Institute’s (NNI) Department of Neurology. Although DRCS started about a year ago, its work is based on Prof Kandiah’s more than 15 years of clinical experience at his dementia clinics at NNI and other tertiary hospitals.

“We use a special blood test to detect abnormal proteins and have found that out of the total cohort of 818 participants, 11 per cent have abnormal levels of amyloid-beta protein in the brain. This is very different from what we know in Western literature,” he says.

“In the West, this can be as high as 45 per cent. This is why we are calling this ‘Asian dementia’, which is different from all the Western studies that have been done so far.”

Another key observation from the Biocis programme is that in the Asian context, dementia affects planning ability and executive function, unlike in the West, where dementia is usually linked to memory loss.

Executive function refers to one’s ability to plan, organise and complete tasks independently. It also includes problem-solving, setting goals and making decisions.

“Planning ability and other executive roles belong to a higher brain function, which affects day-to-day living,” says Prof Kandiah. “In Asian dementia, this is different because it affects a person’s ability to make judgments about what is right and wrong.”

“There have been many cases in Asia where people who are impaired in these areas have become victims of financial fraud. When we opened about a year ago, we did not have this hard data, which was available only early last month,” he adds.

“We focus on individuals who have some form of early-stage cognitive impairment, not those who have already been diagnosed with dementia, and the studies are done on both healthy, as well as impacted, individuals so that we have a basis for comparison.”

The challenge, he says, in treating dementia is that it has to be identified as early as possible, because once brain cells are lost, there is very little that can be done.

“What is also worrying is that about one-third of our participants belong to the young onset dementia group, which is not a trivial number,” he says. “The youngest patient we recently diagnosed is 45 years old.”

Young onset dementia affects those below the age of 65 years, and he notes that Asians are more susceptible to it.

“Lifestyle is a contributing factor as those who are young and have early-onset dementia do not sleep enough, have no cognitive stimulation such as engaging in mental exercises and do not have an active lifestyle,” he observes.

There is an association between lack of exercise and dementia. People with comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes and high cholesterol are also more likely to develop brain damage.

“We have seen that if we can get the patient to adopt a healthier lifestyle, we can control the worsening of the risk factors that lead to dementia,” he says.

One of the research participants for the Biocis programme is Madam Connie Wong, 69, a retired finance and human resources administrator. She lives in an executive maisonette in Jurong with her husband, who is in his 80s.

She visited DRCS in Mandalay Road in 2022 for a battery of tests, including blood tests, brain MRI scans, neuropsychological assessments and a session which tested her ability to recall details from a short passage.

All her tests were provided free, but participants are encouraged to consult a specialist on their own if they want a detailed clinical assessment of their cognition or if there are any abnormal findings.

Her MRI scans revealed white matter in her brain, indicating potential risk factors that may require medical attention.

“I feel that I am slowing down in the last two months, and I am getting more forgetful,” says Madam Wong, who is in good health apart from diabetes, which she keeps under control through medication and diet.

She wanted to be part of the study because of first-hand experience of the ravages of dementia. Her mother, who died in March 2021 at the age of 104, was diagnosed with the condition after living with the disease for seven years.

She was not aware of her mother’s dementia until 2015, when a social worker at the senior activity centre near her mother’s rental flat in Bukit Merah told her that her mother was behaving erratically and could be suffering from dementia. She advised Madam Wong to seek medical help.

After waiting for about 10 months, her mother was finally examined by a gerontologist at Singapore General Hospital. She went through an MRI brain scan and sat a series of tests, including an oral competency test.

“She got all her answers wrong except for one question on whether she knew who was sitting beside her. She answered, ‘Yes, I know that this is my daughter’,” she recounts.

“Towards the last few years of her life, my mother’s personality changed drastically,” recalls Madam Wong. “The same woman who let me ride piggyback in Primary 1 from school to our home became violent and even used her walking stick to attack my Myanmar helper at home.”

But things are looking up for those who have pre-dementia.

One of the biggest breakthroughs in the last two years are two drugs that show promise in halting the progression of dementia. Aducanumab was approved in 2022 by the American Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and lecanemab was just given the green light in 2023.

“These are both very exciting developments in dementia treatment,” says Prof Kandiah.

He has seen the efficacy of these drugs in clinical trials carried out in Singapore. “The drugs were able to slow down the accumulation of amyloid and greater cognitive decline in patients,” he notes.

Next in the pipeline are new yet-to-be-named apps, which gamify cognitive assessments, and can be used by both the public and the medical practitioner to test for cognitive decline.

“We are developing personalised assessments through the upcoming DRCS app to help our patients assess their cognitive functions,” says Prof Kandiah, who expects the app to be rolled out in about a year.

“These apps will be clinically sensitive, affordable and easy to use from the comfort of one’s home and take about five to 10 minutes to complete. They will give a person a good idea of whether he or she has cognitive impairment and if he or she should seek immediate medical attention,” he adds.

If anything, the Biocis study showed that many people go undetected for cognitive impairment, so DRCS wants to reach out to more people by making these apps affordable.

“Very often, clinicians are not able to perform validated cognitive tests on patients due to time constraints,” adds Prof Kandiah. “We have specially designed these apps to make it easier for clinicians in diagnosing cognitive impairment.”

An MRI scan showing higher presence of white spots or “white matter hyperintensity”, a risk factor for mild cognitive impairment in early stages of dementia.

PHOTO: DEMENTIA RESEARCH CENTRE (SINGAPORE)

The Dementia Research Centre (Singapore) is looking for volunteers aged 30 to 95 for its research studies, which comprise a range of free neuropsychological assessments, blood tests and brain scans. To sign up, go to www.drcs.sg

How to spot the early warning signs

Recognising the early symptoms of dementia and getting medical attention quickly can make a big difference in the lives of those affected by cognitive decline, as well as their families. A neurologist is able to draw up a list of treatments such as medication and cognitive improvement interventions at the early stages, but not when the condition has been left undiagnosed for a long period of time.

The following are examples of mild cognitive impairment (MCI), which can worsen and advance into dementia.

Mood and behavioural changes

Emotional dysregulation: When a person is not able to control his or her emotional responses to outside stimulation. This can be seen when a person develops sadness or becomes more anxious.

Impulse dyscontrol: When a person is not able to maintain self-control when faced with a challenging situation. This can manifest in a person becoming more irritable or acting without considering the consequences of his or her actions.

Social inappropriateness: This happens when a person loses inhibitions and becomes insensitive to the feelings of those around him or her and says rude things to others.

Decreased motivation: This can be seen when a person appears to have no goals in life and shows an unwillingness to work. He or she loses interest in previously enjoyed activities or no longer cares about things that used to be important.

Physical changes

Slowness of gait: The speed of walking and overall balance decreases with age, typically for those aged from 60 to 69. This can be seen in the slowing down of a person’s gait in which the stride length is markedly reduced and there is less arm swing.

Reduced grip strength: Research has shown that a weak hand grip is a clear indicator of cognitive decline. This also causes a person to drop everyday items such as mugs or tumblers.

Cautious gait: An inability to walk steadily, as well as being unsure about obstacles along the path, are early indicators of cognitive decline and may lead to a greater frequency of falls.

Cognitive changes

Decline in cognition at an intra-individual level: Clinical tests for intra-individual, which refers to “within a person”, can include reaction tests that gauge how fast the brain is able to solve puzzles or process simple mathematical challenges. Reaction time to stimuli gives an idea of brain activity and health.

Minor errors at work: In the early stages of dementia, a person may make frequent errors at work, find difficulty in planning his or her schedule and forget important dates for office meetings. He or she may also frequently misplace keys and his or her mobile phone and become agitated when he or she is unable to find them.

Changes in vocabulary, grammar and word finding: One of the most obvious signs of cognitive decline is the inability to remember names or find the correct word to complete a sentence when interacting with others. Grammar can also be affected in both verbal and written communications.

Moderate- to severe-stage dementia

Severe forgetfulness: When a person is unable to remember the day of the week, this is when his or her condition has deteriorated rapidly. Introducing interventions such as medication or rehabilitative therapies may be ineffective at this stage.

Inability to manage finances: In the moderate stage, a person will display difficulties counting money, dealing with cash or withdrawing money from an ATM. In the severe stage of dementia, he or she will need constant assistance as he or she will not be able to manage day-to-day functions.

Delusions and hallucinations: In the severe stage of dementia, a person may become violent as he or she may see or hear things that are not there. He or she may also develop thoughts that someone, such as a helper or neighbour, is constantly trying to cause him or her harm.

Frequent falls: As the cognitive functions that govern mobility, balance and strength deteriorate in those with severe-stage dementia, there will be frequent falls. This is the time when round-the-clock medical care needs to be set up to prevent life-threatening accidents.

How to reduce dementia risk and boost brain health

There is no cure for dementia but early detection, maintaining regular contact with a dementia specialist such as a neurologist, as well as improving overall health, can help in reducing one’s risk of suffering from neurodegenerative diseases.

Here are some tips for a “brain-healthy” lifestyle.

1. Phospholipids and phytonutrients for brain nutrition

Prof Kandiah says phospholipids are crucial for brain cells and phospholipid supplementation can help in preventing brain shrinkage, which begins in persons with pre-dementia. Phospholipids are the basic structural component of cell membranes in the brain. Brain lipids comprise about 50 per cent phospholipids.

“A clinical trial with a phospholipid-containing supplement has demonstrated that it is able to slow brain atrophy and reduce cognitive decline if taken at the pre-dementia stage,” says Prof Kandiah.

Souvenaid, which is made by Nutricia, a therapeutic foods and infant formula company, contains a combination of nutrients designed for persons in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease. The daily medical nutrition drink, priced at $20 for four bottles, is available in 125ml bottles at Guardian pharmacies islandwide.

“Phytonutrients, such as ginkgo biloba extract, have also shown in clinical trials to benefit patients with pre-dementia in improving cognition and regulating behaviour,” says Prof Kandiah.

2. Multivitamins

A new study published in late May in the American Journal Of Clinical Nutrition has found that taking a daily multivitamin tablet – which can be bought from supermarkets and pharmacies – helps to improve memory and slow down cognitive decline associated with ageing.

A group of scientists from Harvard Medical School and Columbia University confirmed that data collected from monitoring 3,500 people over the age of 60 who took a multivitamin for seniors called Centrum Silver over a period of three years showed they had better memory than those who received a placebo.

The seniors showed an improvement in their ability to recall items on a cognitive test by 12 per cent compared with their baseline performance three years prior to the testing.

Those with heart disease who took multivitamins also showed the biggest improvements in memory compared with those without heart issues.

3. Regular exercise and Mediterranean diet

Prof Kandiah says those above the age of 60 who include a daily regimen of walking and light exercise, together with a Mediterranean diet rich in plant-based oils such as olive oil, fruit, nuts, brown rice and greens, showed better results than those who maintained a sedentary lifestyle with no controls in their caloric intake.

“Daily walking has a range of benefits for the elderly, especially improving balance and coordination, thus delaying frailty,” he says. “It also strengthens muscles, improves stamina and can help to reduce blood pressure.”

4. Brain stimulation

One of the most important adjustments to the daily routine of those above 60 should involve activities that provide stimulation to the brain.

Prof Kandiah says moving from passive watching of programmes or movies on television and streaming platforms to active participation in recalling the details of the segments is important.

“It’s vital to remember what you just watched on TV,” says Prof Kandiah. “This is how you can stimulate the brain’s ability to create and retrieve memories. Persons with severe dementia often grapple with memory loss caused by gradual damage to the brain cells over time.”

He advises writing down details about a movie, TV show or social media reel immediately after it has ended to strengthen the ability to recall memories such as the plot and names of key actors, and critique the way it was directed or produced.

“Other brain stimulation activities that can be done weekly include journaling, where you describe what happened earlier in the day; and sketchbooking, where you put together newspaper clippings, photos or mementoes to describe the main events for a particular day or week. Strengthening memory both descriptively and visually gives a workout to the brain and keeps one alert.”

5. Tech wearables

Another way to monitor overall health is through technology-enabled wearable gadgets available in stores such as Apple and Fitbit.

The latest Apple watches are able to alert a caregiver if someone has fallen and is motionless. They also have an electrical heart rate sensor that, along with an app, allows one to take an electrocardiogram. The watches can also monitor the quality and duration of sleep, which are crucial in maintaining a healthy lifestyle.

Fitbit, which is popular with young and health-conscious people, is also a good wearable for seniors who opt for active ageing. It has features that allow those over 60 to keep track of their overall health, including to keep moving, reduce stress and enjoy better sleep.

6. Dementia help

For dementia-related issues and community care options, check out these helplines:

Agency for Integrated Care Hotline: 1800-650-6060

Dementia Helpline: 6377-0700

DementiaHub.SG: Go to DementiaHub’s website

Institute of Mental Health’s Mental Health Helpline: 6389-2222 (24 hours)

Samaritans of Singapore: 1800-221-4444 (24 hours) /1-767 (24 hours)

Care Corner Counselling Centre: 1800-353-5800

ComCare Hotline: 1800-222-0000 (24 hours)

Information provided by Dementia Singapore and the Agency for Integrated Care