Is Asia ready for... fragmented societies?

The splintering of a shrinking world

In Asia, societal fault lines new and old are being weaponised through social media

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Japan’s population struggles are a harbinger of what lies ahead for other East Asian societies such as China and South Korea.

PHOTO: REUTERS

Looked at in some ways, the world has never been closer or had so much to celebrate.

People are living longer lives. Families and friendships around the world are secured and sustained by exchanges on Facebook posts, WhatsApp chat groups and Zoom calls. Communities of interest – whether of those who love cycling, golf, collecting stamps or playing bridge remotely – link people across continents.

A shooting in a Texas school

Disappointingly, prejudices and biases, too, can be distributed just as promptly, magnified even more as a frighteningly large number of people seek out the comfort of echo chambers that conform to their own predilections and prejudices.

Meanwhile, in country after country, the middle ground in democratic politics appears to be shrinking. Fiery rhetoric, fuelled by social media, can set off political conflagrations. The resentments and prejudices generated by existing societal fissures used to be more easily contained, smouldering beneath the surface. No longer.

Kindling and accelerant

Social media has served as both kindling and accelerant – first by stoking anger and grievances among like-minded people and then propelling these outwards. The causes may be different, but given the rapid amplification of messaging, the risk of igniting a wildfire is always there, especially if borne on winds of disinformation and misinformation.

In a fragmented society, words are dangerous weapons in the hands of charismatic politicians. They can whip up a mob, as in Donald Trump’s America where people who would not accept his election defeat by Mr Joe Biden in 2020 stormed the Capitol,

More recently, in Pakistan, thousands of former premier Imran Khan’s followers took to the streets in Islamabad, Karachi, Lahore, Peshawar and other cities in May in protest against his eviction from power.

In his bitter test of wills with the mighty military establishment, the former cricket star turned politician had a handy weapon of his own: YouTube. Through it, he exhorted his followers to rally wherever they may be, even in remote villages. “Freedom does not come easily. You have to snatch it. You have to sacrifice for it,” he urged.

Asia, home to some of the fastest expanding economies, rising wealth, ageing societies as well as widening digital networks, sits in the vortex of the cross currents of a variety of conflicting impulses. They are manifesting at a time when societal fault lines new and old are easily weaponised through digital technology, be it viral memes on social media, the rapid relaying of disinformation through closed messaging groups, or the propagation of deliberate falsehoods and deep fakes.

Is Asia able to deal with such treacherous currents even as it seeks to exploit the benefits of digital connections?

“Digital technology is a tool, rather like a knife or fire,” Dr Carol Soon, who heads the society and culture department at the Institute of Policy Studies, told The Straits Times. “It can be used for both good and bad. For most of us, digital technology magnifies who we are and what we do. For instance, some cyber bullies tend to be bullies in real life, too.”

SPH Media will be holding a two-day conference on the future of Asia on Oct 4 and Oct 5.

The by-invitation Asia Future Summit 2023 will bring together 300 delegates, thought leaders, policymakers and diplomats, and feature more than 20 speakers. They include Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong, former prime minister of Australia John Howard, former United States ambassador to Singapore Jon Huntsman and Mr Narayana Murthy, founder of Infosys.

The event at The Ritz-Carlton, Millenia Singapore, will also discuss the world views of Mr Lee Kuan Yew, Singapore’s founding prime minister who died in 2015 and who would have turned 100 this year.

OCBC is the presenting sponsor of the event.

Gender politics

South Korean politics offers an interesting case study on how deeply embedded social norms can be called into question and weaponised by opposing camps. For South Korean women, 2018 was a watershed year for the #MeToo movement.

Once the taboo was broken, similar accusations were levelled by others against a presidential hopeful, an award-winning movie director and an acclaimed poet. As the #MeToo movement surged in numbers with the help of social media, particularly Twitter (now known as X), calls for better pay for women followed. But this was not the end of it.

The backlash came in the presidential election of 2022. What was unusual was that in addition to the usual appeals along regional and conservative-progressive lines, gender politics played a part. The conservative camp made a targeted appeal to South Korean men, fanning their fears of “a female-dominated society” and calling for an end to “reverse discrimination against men” and the abolition of the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family. Exit polls on election day showed 59 per cent of male respondents in their 20s voted for Mr Yoon Suk-yeol, the conservative candidate, compared with just 34 per cent of women in the same age group.

The power of social media first enabled South Korean women to air their grievances and connect in a collective push for action. The same tech-enabled messaging deepened the gender divide by spurring pushback by young men who resent women getting the upper hand via gender equality policies, not to mention their exemption from compulsory military service.

Social splinters

The deepening contradictions in Asian society show up in myriad other ways.

Demographics? Well, Japanese department stores are reporting that adult diapers are outselling children’s nappies as the society ages. Japan’s population struggles

Class divide and income disparities? In India, the waiting list for high-end cars such as Tesla and Mercedes can be months long, while vehicles that the middle class can afford sit unsold in showrooms.

Religion? Malaysia’s overlapping “green waves” triggered by fundamentalist groups and mainstream parties struggling to meet the challenge by making their own political adjustments are being closely monitored by Asean neighbours, particularly those grappling with the challenges of operating multi-ethnic, multi-religious societies.

Sexual preferences? It wasn’t long ago that Singapore saw the birth of a “wear white” movement, meant to take on the annual Pink Dot rally championing the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender community.

Quite frequently, some of these fault lines, such as race and inequality, overlap.

Take for example the United States, where Trump rose to power by stoking the dissatisfaction of malcontents, especially in middle America, who felt left out of the benefits of globalisation that so fuelled prosperity in America’s coastal states. He also tuned up ethnic issues, playing on the anxieties of those white voters who feared being swamped by non-whites.

Dr Soon of IPS noted that as Trump’s chances of retaining the presidency began to slip, leading up to the storming of the US Capitol in January 2021, social media platforms such as Telegram saw heightened discussions among pro-Trump groups.

But Trump is hardly alone in playing the race card twinned with the inequality card.

Malaysia’s former prime minister Mahathir Mohamad, for example, owes much of his career to his astute use of the race card

Three years ago, Tun Dr Mahathir outdid himself by claiming that Malaysian Chinese have become “extremely rich and own practically all the towns in Malaysia”.

Closer examination of Malaysia’s household income data reveals the level of exaggeration Dr Mahathir had deployed in his attempt to score political points.

What’s the truth? Nationally, Malaysian Chinese households did receive 36.4 per cent more income than bumiputera households, but this was partly because of the much larger share of bumiputeras residing in rural Malaysia versus Chinese who tend to live more around the cities, where the high-paying jobs are generally found.

In urban Malaysia, which would have been the more accurate comparison, Chinese households received a narrower 23.1 per cent more income than bumiputera ones.

Income divide

Across Asia, as Dr Mahathir’s gambit implicitly suggests, class is emerging as a major fault line, even in societies such as India, long thought to be principally stratified along caste and religious lines, or Sri Lanka, where ethnicity has been a key issue.

In crucial elections to fill the state assembly in southern India’s Karnataka this year, the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) received a drubbing despite sustained campaigning by its Hindu nationalist prime minister, Mr Narendra Modi.

While the top 16 per cent income group voted overwhelmingly for the BJP, the remaining 84 per cent largely voted for the opposition Congress. The poorer the voter, the higher the vote share for Congress.

Mr Modi’s vaunted charisma and powerful oratory notwithstanding, voters in the teeming middle and lower income levels found their sense of deprivation or relative misfortune a more compelling instinct to respond to than the majority religion-based campaign themes of the BJP.

The gap between the haves and have-nots has also emerged as an issue in Singapore: A 2018 study commissioned by OnePeople.sg revealed that about half of the 1,036 surveyed felt that income inequality is the factor most likely to cause a social divide here.

Interestingly, only one in five respondents felt that race was the most likely to cause a social divide, and an almost similar proportion felt that way about religion. Dr Janil Puthucheary, chairman of OnePeople.sg – the national body promoting harmony – has described the survey results that called attention to the class divide as “unsettling”.

“Today, it’s the divide between the haves and the have-nots that’s creating the most tension,” he was quoted by CNA as saying. “This is going to be an explosive issue because it challenges some of the values that we hold so firmly and dearly.”

Age divide

And thus, new social fissures grow even as old ones remain. One that Asia needs to watch out for is the age divide.

Rising longevity, falling fertility levels and a shrinking workforce will put increasing pressure on state coffers while accentuating intergenerational tensions between retirees and working adults. The latter face a double whammy – more seniors to support at home with fewer siblings to share the burden, and higher taxes.

Stunningly, senior Japanese politician Taro Aso – then finance minister – grabbed global headlines a decade ago by urging older folk in his country, where the life expectancy just topped 85 years, to “hurry up and die” in order to avoid straining the country’s finances.

The occasional newspaper story suggests that ubasute, the age-old Japanese tradition of “granny dumping” or abandoning an elderly relative in a remote spot, may have found new life.

Some countries like Singapore have passed legislation to function as a last-gasp measure in case counselling fails to convince the young to provide a measure of care for needy parents.

More and more Asian societies will need such top-down measures as life expectancy advances and the young find filial duties competing with their own private yearnings for self-fulfilment.

Holding it together

To be sure, it is not that everything is a slide to the bottom. Indeed, there have been standout cases of complex societies finding reasonable space for all these competing pulls to co-exist. Indonesia has done a fair job maintaining a pluralistic, multifaith democracy, even as majoritarian tendencies have got more accentuated in some of its neighbours.

Asian societies – minus some big-population states like India and Pakistan perhaps – have also done a fair job of holding societies together as they emerge from Covid-19.

In August 2022, as the world slowly emerged from the pandemic, a median of 61 per cent of people surveyed across 19 countries by Pew Research Centre thought their country was more divided than before the coronavirus outbreak.

Interestingly, three of the four Asian nations in the survey – Japan, Malaysia and Singapore – stood out as places where only four in 10 or fewer believe they are now more divided. Singapore was the lowest – a mere 22 per cent felt society was more divided.

One reason for Singapore’s encouraging score could be the redistributive effect of government transfers during the pandemic to staunch the fallout on the economy and society.

But Covid-19 also brought fresh divisions. According to the United Nations, the digital divide became the fresh face of inequality in the Covid-19 era because digitally connected and well-prepared countries, industries, companies and individuals fared well, while the poorest and those most vulnerable were hit the hardest.

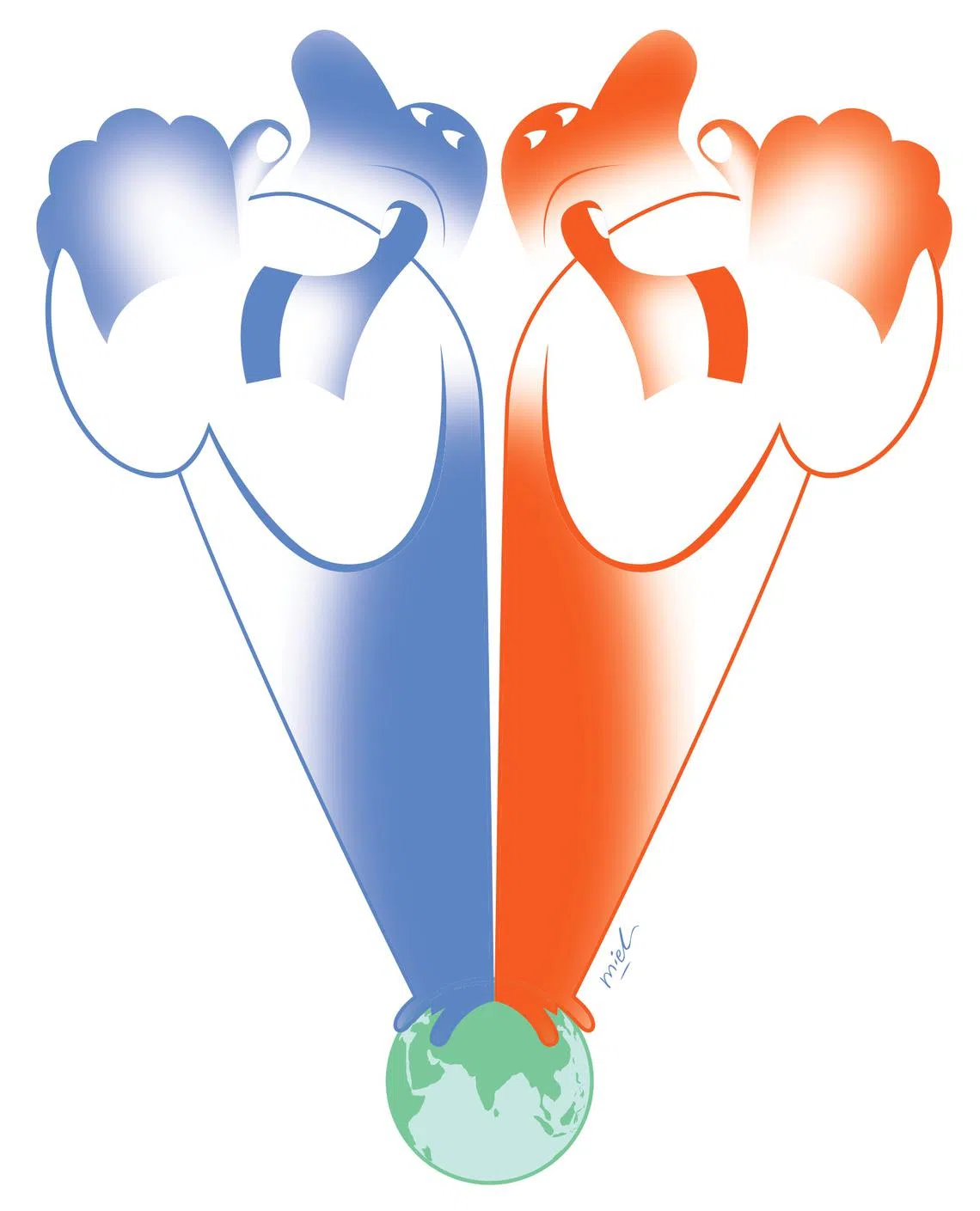

ST ILLUSTRATION: MIEL

Digital dilemma

The Asia-Pacific fared the worst among five regions of the world surveyed by the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific for its 2022 digital transformation report. While Singapore and Japan were outliers, half of the people in the region do not even have access to the Internet, it said.

But what this also means is that half of those who are connected face the danger of disinformation warfare.

And even those who are fortunate to get connected can face firewalls – see how China has clamped down on sharing of sensitive information deemed inconvenient to the state.

In other cases, there has been deliberate disruption of networks – the prolonged Internet shutdowns in Myanmar,

Still, on balance, Asia is probably better off than many other parts of the world. America’s many contradictions are in overflow mode and new ones are poised to emerge as the racial mix of society changes; white Americans will soon become a minority, and that will produce its own issues. Right-wing, racist elements are on the rise in key parts of Europe.

What’s more, the faintest hints are emerging that the excesses of social media are leading to a loss of credibility for the medium that could potentially limit its pernicious effects.

Dr Sanjaya Baru, media adviser to India’s then Prime Minister Manmohan Singh between 2004 and 2008, remembers raising eyebrows in the government when he opened a Facebook account.

“Many thought it wasn’t correct on my part to do that,” he recalled. “Today, the prime minister of India has a Facebook account, just as he has an active Twitter handle.”

Dr Baru, a renowned expert in geo-economics, said the Arab Spring protests and Mr Modi’s rise to national leadership partly on the back of astute social messaging represent the heyday of social media’s impact.

“The relevance of social media is petering out,” he said.

“Trust in both mainstream and social media is dwindling because both are being misused. For politicians, therefore, direct contact with people is again getting important.”

The jury is still out on whether Asia has what it takes to meet the intertwined challenges of social fragmentation and social media mayhem, but if Dr Baru is right, it would mean politics is poised to shift back to the “see me, hear me, touch me” style of the old school. Maybe, in this age of deep fakes, that isn’t such a bad thing.

• OCBC is the presenting sponsor for the Asia Future Summit 2023. The event is also supported by Guocoland and Kingsford Group.