10-year-old jungle bridge over BKE proves a lifeline for pangolins, mousedeer and other wildlife

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

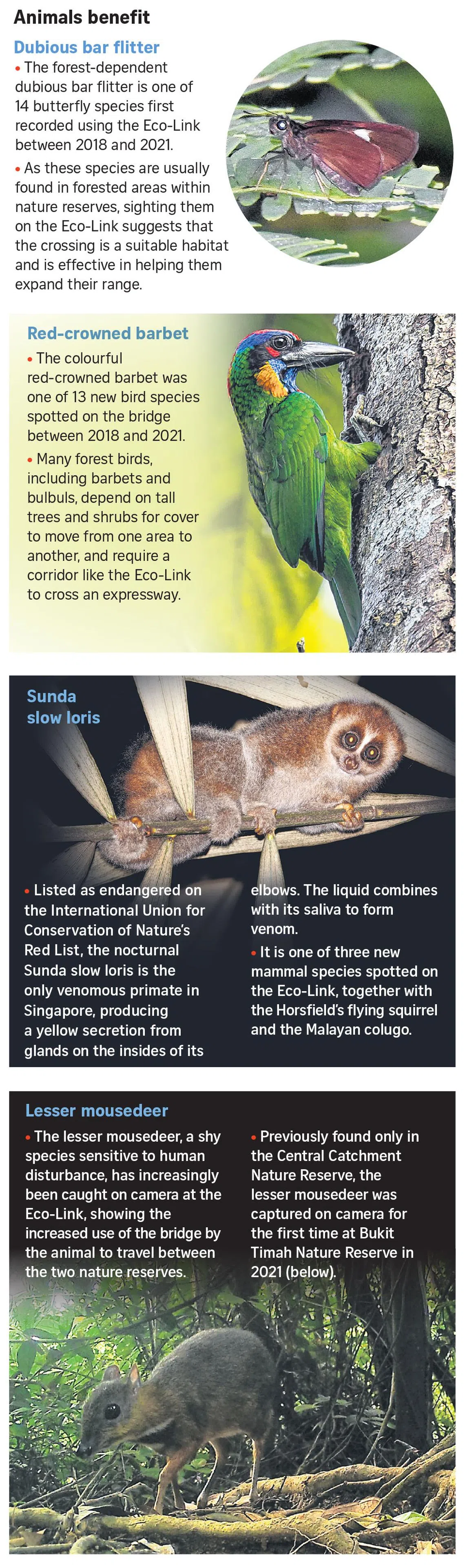

Species seen at the Eco-Link@BKE include (clockwise from top left) the Sunda slow loris, lesser mousedeer, dubious bar flitter and Horsfield’s flying squirrel.

PHOTOS: NORMAN LIM, NPARKS, SEBASTIAN OW, NICK BAKER

SINGAPORE – An overhead bridge linking two of the Republic’s critical green spaces has saved many native creatures from ending up as roadkill, and provided a safe passage for them between their habitats in the Bukit Timah and Central Catchment nature reserves.

The plight of pangolins and other threatened animals in the two largest nature reserves in Singapore has eased over the past decade, with less roadkill recorded along the Bukit Timah Expressway (BKE). Since the bridge started taking shape in April 2014, there has been a reduction of more than 90 per cent in the number of pangolins killed on roads in the area.

Between 1994 and March 2014, an average of two critically endangered Sunda pangolins were hit by vehicles in the BKE area each year. Others killed on the roads included the common palm civet, long-tailed macaque, wild boar and a number of reptile species. Between April 2014 and April 2023, however, only one pangolin was killed by road traffic, said Mr Lim Liang Jim, group director of conservation at the National Parks Board (NParks), which commemorated the 10th anniversary of the Eco-Link@BKE bridge

Between 2015 and 2022, NParks also recorded about one roadkill incident per year involving other wildlife in the area, such as macaques and wild boars, added Mr Lim.

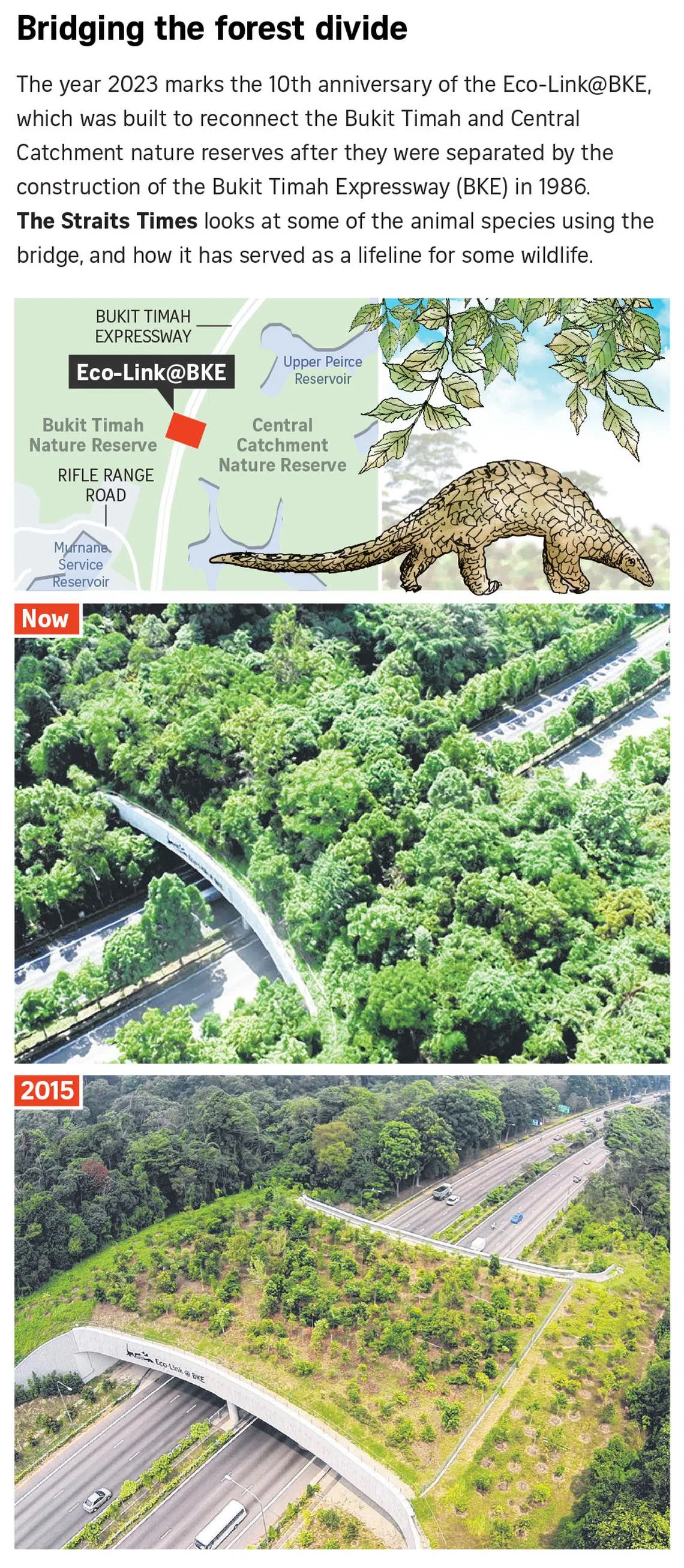

The Eco-Link@BKE bridge, which began construction in 2013, connects the two nature reserves across the expressway. More than 3,000 native plants formed the foundation of the 50m-wide bridge; by 2015, it started looking like a suspended forest.

A first of its kind in South-east Asia, the 62m-long bridge for animals was built to alleviate a major problem for native wildlife in urbanised Singapore – the fragmentation of habitats. The BKE was a physical barrier separating the two nature reserves, isolating habitats and populations of forest-dwelling animals that cannot adapt to the urban environment.

As groups of these animals were divided by the six-lane BKE, there was a risk of the biological fitness of each population weakening as a result of inbreeding among genetically related individuals within a species. This could lead to the species’ local extinction, states NParks’ Handbook on Habitat Restoration, which was released on Thursday.

The solution was to let the wildlife at both nature reserves mix, and the forest-like Eco-Link@BKE enabled that.

As at 2021, about 100 species of fauna crossing the bridge have been recorded by motion-sensor cameras. The more common ones are macaques and the common palm civet. Researchers were thrilled to also spy the rarely sighted and shy lesser mousedeer, one of the world’s smallest hoofed animals.

Over the years, the lesser mousedeer has been captured on camera traps on the bridge more often: In 2021, there was at least one recorded sighting every month over eight months, compared with 2018, when the species appeared only about four times, said NParks.

While the mousedeer was known to reside only in the Central Catchment Nature Reserve, it was sighted in Bukit Timah Nature Reserve in 2021 for the first time, suggesting that the bridge allowed the species range – an area where an animal can be found – to expand.

The red-crowned barbet has made appearances at the Eco-Link@BKE.

PHOTO: FRANCIS YAP

Between 2018 and 2021, 31 unexpected butterfly, bird and mammal species also made appearances at the Eco-Link@BKE. These included the Horsfield’s flying squirrel, Malayan colugo – recognisable by its wide, round eyes – the Sunda slow loris and the red-crowned barbet bird.

The bridge was initially targeted at forest-dwelling mammals with restricted movements and species that tend to be roadkill victims, such as the pangolin, civet and mousedeer.

The Malayan colugo spotted at the Eco-Link@BKE.

PHOTO: CAI YIXIONG

“The discovery of additional species using the bridge reflects the effectiveness of the Eco-Link@BKE and provides insights for ongoing efforts to strengthen ecological connectivity between our green spaces,” said NParks.

In 2024, NParks will embark on its next round of camera trap surveys on the bridge to continue monitoring wildlife movements there, said National Development Minister Desmond Lee in a Facebook post on Thursday.

While the bridge has softened the BKE’s impact on the primary and secondary forests of both nature reserves, it cannot alone fully eliminate fragmented habitats and roadkill.

A 140m-long wildlife bridge across Mandai Lake Road

Other wildlife crossing aids have been set up alongside the Eco-Link@BKE to help native animals better move between the two nature reserves and parks surrounding them.

Those include aerial rope bridges for macaques, poles for colugos and underground culverts.

By 2026, another bridge – for both people and animals – will be built to connect the Bukit Timah Nature Reserve and the Western Water Catchment area via Bukit Batok Nature Park.

Dr Anuj Jain, founding director of bioSEA, a company that specialises in ecological design, noted that sound pollution from the expressway could limit the effectiveness of Eco-Link@BKE.

“A long-term solution could be covering the BKE near both sides of the Eco-Link with a shell-like roof structure that could soundproof the nature reserves and Eco-Link better. If budget allows, the roof structure could be greened with plants to allow for wider connectivity,” he said.