How this pangolin sperm bank in S’pore is giving the world’s most trafficked mammal a lifeline

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

(Left) Mandai Wildlife Group assistant vice-president for veterinary healthcare Heng Yirui, veterinary nurse Maxine Ng and senior veterinary nurse Clara Yeo conduct a full heath check on a male Sunda pangolin.

ST PHOTO: GAVIN FOO

Follow topic:

SINGAPORE – As the clock ticked towards the awakening of the sedated Sunda pangolin, veterinarians scanned its vitals before nimbly collecting semen from the critically endangered animal.

The adult male pangolin had been rescued hours earlier on Feb 13 by the Animal Concerns Research and Education Society (Acres) after a resident found it stranded on a gate in a housing estate in northern Singapore.

Not a drop of semen was spilt by staff from Mandai Wildlife Group, as they took pains to study and store the sample in a sperm bank that could give the world’s most trafficked mammal a lifeline in the future.

This comes as pangolin populations are declining across the globe, despite legal protection to shield eight of its species from extinction.

In the last decade alone, an estimated one million pangolins were poached to feed the illegal appetite for the species’ meat, skin and scales, according to the World Wide Fund for Nature.

While poaching remains low in Singapore, conservationists said motor vehicles have become the greatest threat to their survival here, following a dramatic increase over the past three years in the number of pangolins killed in road accidents.

In conjunction with World Pangolin Day on Feb 17, The Straits Times takes stock of national efforts to save the native mammal, which plays an important role in the ecosystem by controlling populations of ants and termites.

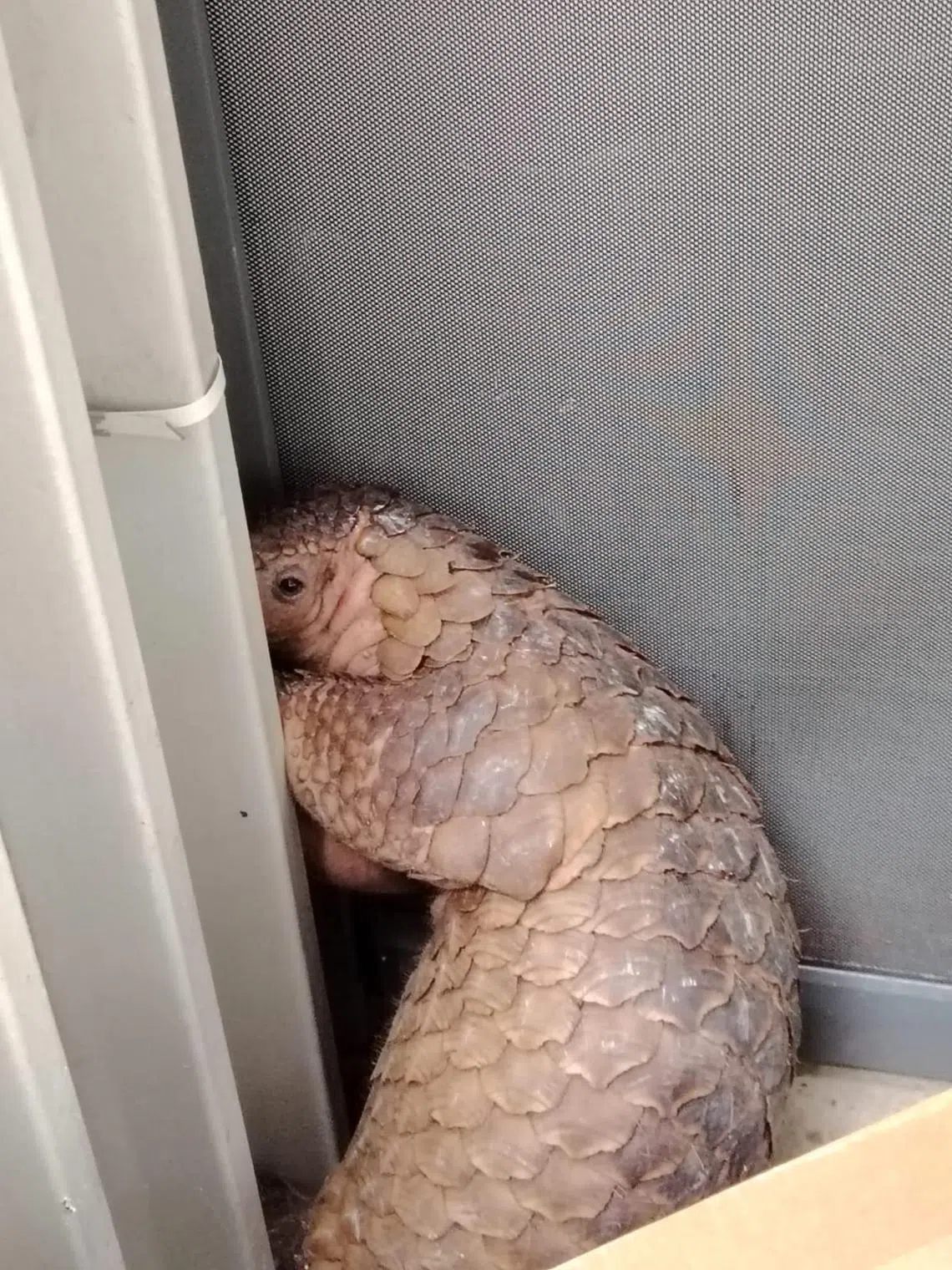

A resident found a male Sunda pangolin stuck in a gate on Feb 13 in a private housing estate in northern Singapore. It was rescued by Acres.

PHOTO: ACRES

Dr Charlene Yeong, a veterinarian at Mandai Wildlife Group and its conservation arm, said Singapore enjoys the privilege of being home to healthy wild pangolins.

She said: “Most of the ones seen by humans are those that go through the wildlife trade, many of which are in very poor health.”

The nocturnal creatures are so elusive that little is known about them, including how many there are in Singapore.

The pangolin undergoes a full health check at the Wildlife Healthcare and Research Centre on Feb 13.

ST PHOTO: GAVIN FOO

The number of pangolins left here has been hard to pin down, even after the Singapore Pangolin Working Group launched a national conservation plan for the mammals in 2018 to gather information on the species’ status in the wild and safeguard its future over half a century.

Mr Lim Liang Jim, group director for conservation at the National Parks Board (NParks), said the agency remains optimistic about the pangolins’ fate even though a reliable estimate cannot be given for its population.

There was an increase in sightings of pangolins and their babies on camera traps at the Central Catchment Nature Reserve between 2020 and 2023, he said.

Breakthroughs

More pangolins have also been detected overall in recent years.

As part of the concerted effort to crack the many mysteries surrounding the Sunda pangolin, all reported cases of dead or injured pangolins found in urban spaces are taken to Mandai Wildlife Group’s Wildlife Healthcare and Research Centre.

Between 2021 and 2023, an average of more than 40 pangolins, both dead and alive, were admitted annually.

This is up from an average of about 20 annually between 2015 and 2020.

Each pangolin examined is an opportunity for vets to learn everything they can about the creature, said Dr Yeong, who is a senior manager of wildlife health and rehabilitation at Mandai Nature.

The co-chair of the Singapore Pangolin Working Group said: “In general, to know what’s abnormal, we need to identify what’s normal first.

“This allows us to better treat animals in a bespoke manner.”

Treating and rehabilitating injured pangolins, which are creatures that can be complicated to operate on because of their scaly armour, have paved the way for several breakthroughs.

An intubated male Sunda pangolin lies on a table at the Wildlife Healthcare and Research Centre on Feb 13.

ST PHOTO: GAVIN FOO

For instance, Mandai Wildlife Group’s vets have discovered how to place a tube into the mammal’s narrow snout that can help it breathe under sedation, a task once considered near impossible.

On a grim note, conservationists said more pangolins have been turning up dead in recent years due to road accidents.

Between 2021 and 2023, NParks received an average of about 20 reported cases of pangolins being killed on roads annually, up from a yearly average of around four cases in the previous three years.

Dr Yeong and Mr Lim said the increase can be attributed to multiple factors, including greater public awareness about pangolins and how to report such cases.

The loss of vegetated habitat in recent years could be another reason for the growing trend of pangolins dying on roads, said Mandai Wildlife Group animal care officer Ade Kurniawan, who has looked after pangolins for nearly a decade.

A pangolin released in the Central Catchment Nature Reserve by NParks climbing a tree on Oct 2, 2023.

PHOTO: NPARKS

Sunda pangolins live in forested land, and climb trees to feed on ant nests or rest during the day. They also shelter in burrows.

Said Mr Kurniawan: “In recent years, we’ve lost Tengah forest to development, and that was a key connection point between the Western Catchment forest and the Central Catchment Nature Reserve. So we might be seeing more pangolin deaths because their habitat is decreasing.”

Acres’ co-executive Kalaivanan Balakrishnan said pangolins may also venture out of forests as a result of the weather and in search of mates, but they have to be rescued as the mammals have not adapted to living in urban areas, unlike civets and otters.

In 2023, the charity rescued about 20 pangolins.

Responding to concerns about the rise in roadkill, Mr Lim said NParks has been creating safe crossings for both terrestrial and tree-dwelling fauna by building underground passages and establishing nature corridors, among other measures.

Acting now before it’s too late

Fortunately, a fraction of pangolins that wind up getting hit by motor vehicles do survive and when found, the animals can get a second home at the Mandai Wildlife Reserve.

Berani, a male pangolin that received the world’s first known pangolin bone surgery in 2018.

PHOTO: MANDAI WILDLIFE GROUP

Among these animals is Berani, a male pangolin that underwent the world’s first known pangolin musculoskeletal surgery in 2018, after he suffered a fractured thigh bone linked to a motor accident.

Despite Berani’s injury healing well, he has been kept at the Night Safari to monitor his health for any long-term consequences of his injury, said Dr Yeong.

The park houses another three pangolins: a female estimated to be two years of age, a mother and her son.

Said Mr Kurniawan: “If one day, there is a need for species recovery, the idea is to eventually breed and release these animals when required.”

At the moment, there is no information to indicate that the strategy is urgently needed, but the knowledge of reproduction needs to be acquired before the writing is on the wall, he added.

He said: “If you look back at all the species that have declined, you can’t wait until they are extinct in the wild or critically endangered to the point of having no animals to decide that it’s a good time to start rescuing the animal or putting it into human care and figuring out how it breeds.

“By then, it will be too late.”

Finicky eaters

A Sunda pangolin resting on a tree in Night Safari in 2021. The creature can sleep for up to 22 hours each day.

PHOTO: ZAOBAO

Caring for pangolins, however, is a notoriously difficult task that zookeepers worldwide are still trying to perfect.

The toothless animals with a taste for certain ants and termites are hard to sustain as they are finicky eaters, one of the many reasons why they should not be kept as pets, said Mr Kurniawan.

Pangolins can eat up to 200g of ants or more each night, he added.

Since the first pangolin arrived in the 1990s, it has taken Mandai Wildlife Group years to settle on a nutritious insect-based diet that includes ant eggs.

Ultimately, the goal for most rescued pangolins admitted into the Wildlife Healthcare and Research Centre is for them to be released into the wild, said Dr Yeong.

These make up about 85 per cent of live pangolins taken to the animal hospital since 2015.

Pangolin babies that have been separated from their parents are hand-raised and typically released once they hit a minimum weight and pass a fitness test that ensures they can survive alone in the wild.

Mandai Wildlife Group assistant vice-president for veterinary healthcare Heng Yirui (centre) engraves a unique identifier on the scales of a male Sunda pangolin during a full health check at the Wildlife Healthcare and Research Centre on Feb 13.

ST PHOTO: GAVIN FOO

Like the pangolin rescued on Feb 13, those that have been released are microchipped and sport a “tattoo”, helping researchers identify the creatures when they are caught on camera in the wild.

Pangolins do not shed their scales, which are made of keratin (the material that makes up hair and fingernails). This allows vets to engrave a unique identifier without hurting the creatures.

Once engraved, they are then released into the Central Catchment Nature Reserve, Singapore’s largest nature reserve spanning more than 2,000ha of forest.

Members of the public can contribute to the nationwide effort to save pangolins by submitting their sightings

Said Mr Kurniawan: “Right now, our knowledge on where they are remains limited to roadkill information or cases from Acres.

“But the rare encounters at HDB blocks actually help us see where they are dispersing to; they give us a bigger picture.”

The pangolin found by a resident was released in the Central Catchment Nature Reserve on Feb 14, a day after a health check-up at the Wildlife Healthcare and Research Centre. Pangolins curl up into a ball to protect themselves with their scales when they feel threatened.

PHOTO: NPARKS

What to do if you see a pangolin

Observe it from a safe distance and do not approach it. Sightings can be recorded via the Singapore Pangolin Working Group website.

Don’t handle the animal. Pangolins are wild animals that have powerful claws that they can use to defend themselves when they feel threatened. Going too close to a pangolin mother carrying a baby on her back can also cause the baby to fall off and result in the mother abandoning it.

If the pangolin is in an urban space, call NParks’ Animal Response Centre at 1800-476-1600 or Acres at 9783-7782.

Drivers near nature areas should keep to speed limits and slow down. The slow-moving pangolins are often injured or killed by vehicles when they stray too far from the forested areas onto roads.

The public can also contribute to the pangolin’s long-term survival by not purchasing any pangolin products, such as meat, scales, and medicinal products.

More information can be found on the

Our Wild Neighbours website

.