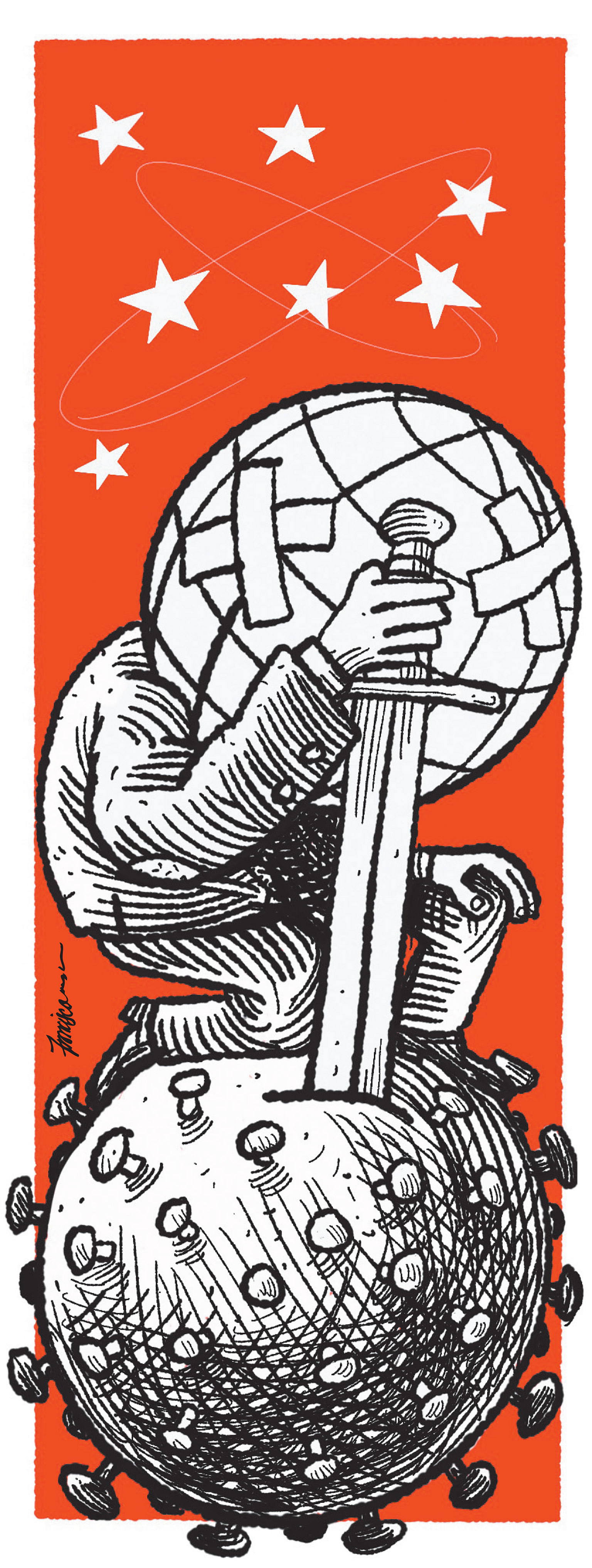

The full impact of the Covid-19 outbreak is yet unknown, but what is clear by now is that it is a global crisis, spread by a virus that pays no heed to physical, cultural or ideological borders. And yet a global response, so necessary given the urgency and the pandemic's reach, has for the most part been lacking.

Instead, we are witnessing a battle of competing narratives, focusing on how different cultures and political systems have dealt better or worse with the challenges posed by the coronavirus.

Casting responses to the virus in such antithetical terms is ill-informed and unproductive; rather than encouraging a much needed collective effort towards global cooperation against a common threat, they sharpen cleavages and reinforce biases.

COMPETING NARRATIVES

A common thread in this contest is the insinuation of cultural characteristics associated with the origins of the virus. When the coronavirus first emerged in Wuhan, it quickly acquired a racial dimension, with epithets such as "kung-flu", "China virus" and "Wuhan virus" applied to it.

It should hardly be surprising that this nomenclature would trigger xenophobia in the United States, Australia and Europe, where anti-Chinese biases surfaced and cases of racial harassment increased.

As the virus made its way across the globe, however, a twist to this cultural narrative could be discerned. This time, it was about how countries in the Western world are lagging behind their Asian counterparts in efforts to curb the spread of the virus. This was evident in headlines such as "How Asian Countries Acted While The West Dithered", "Why The West Will Be Hit Harder" and "Why East Beats West In The War Against Coronavirus".

According to this train of thought, Asian societies have been more successful in arresting the spread of the coronavirus because they prioritised the community over the individual. Asian societies, it is said, have an edge over the West because their people are more willing to comply with instructions from central authorities and overlook privacy concerns in accepting surveillance technologies used in contact tracing.

For advocates of this argument, the fact that healthcare equipment is being donated by China and Taiwan to European countries barely coping with the outbreak serves only to reinforce their line of reasoning.

What to make of this narrative?

There is no doubt that some Asian governments have reacted swiftly and decisively to contain the contagion, just as there is reason to lament the dithering and denial that was all too evident in some Western countries as the virus made its way to their shores.

Yet, for every Italy or the US in the West, there is a Germany or Iceland where the virus has been kept under control. Likewise, for every Taiwan or South Korea, there is an Indonesia or Philippines. Even Singapore is now beset by a new wave of infections after successfully fending off a first wave.

ARE DEMOCRACIES DISADVANTAGED?

There is a corollary to this line of argument: It suggests that centralised states have proven more effective than liberal democracies in handling the virus outbreak and flattening the curve.

This argument has been made most robustly in the case of China and how it brought its outbreak under control. After initial attempts to play down a growing crisis, once the Chinese political leadership came to terms with its severity, it acted quickly and boldly to stop its spread. Chinese citizens bit the bullet as tough quarantine measures were imposed on millions in affected cities.

The full measure of Chinese state capacity and technological prowess was brought to bear on the virus. Famously, an entire hospital was built in less than two weeks in Wuhan (a feat that would later be matched in Britain with the building of the NHS Nightingale London and NHS Manchester hospitals).

China's no-nonsense response stands in stark contrast to that from liberal democracies, for whom even something as routine as public temperature taking threatens to become an existential issue of infringement of civil liberties. In several European countries, governments lost precious time when they demurred on controversial emergency measures for this reason. In Britain, Prime Minister Boris Johnson stubbornly defended the right of people to freedom of movement and exchange until the sheer number of infections forced the government to call for a lockdown.

To add to the sense of disunity, rows over provincial and state rights broke out over the allocation of scarce medical equipment in Italy and the US. When these Western governments eventually imposed more stringent controls, activists decried the erosion of democracy and individual liberty while civil libertarians fulminated against the encroachment of the state into their everyday lives. The New York Times reported how "the virus comes for democracy", while Forbes suggested it is "threatening freedom and democracy across the globe".

Do political systems matter when it comes to handling a crisis?

SEE THE TREES

At first glance, maybe so. Less encumbered by diffusion of authority that might hinder optimal crisis management, centralised systems are presumably better placed to push through tough but necessary legislation, especially when time is of the essence.

By this token, democracies may face a structural disadvantage given the need to take into account a baffling array of interest groups and lobbies; all the more so if it is a federal system of democracy, where states enjoy varying degrees of autonomy to deal with crises such as health pandemics.

Countries with a strong libertarian culture of distrust of government baked into certain segments of their societies, such as in the US, face an especially hard time. Having said that, a close look at how societies have responded to the crisis suggests that for every democracy that has struggled, there have been others that have proven effective.

Taiwan and South Korea readily embraced physical distancing (ironic as this may sound), while citizens of Denmark, Germany (a federal system) and New Zealand accepted without question the urgency of a lockdown once signs of the virus emerged within their borders. What worked for these democracies - no less hampered structurally by the existence of multiple stakeholders - and many others like them was a high degree of trust in their leadership and government. Not to put too fine a point on it, controlling the Covid-19 outbreak is not about geography, culture or political systems. It has everything to do with good leadership, good governance and good decision-making.

To be sure, these are still uncertain days, and we do not know if - or when - a new wave might hit. Nevertheless, with the benefit of hindsight we know that those places that have managed to control the outbreak thus far are those that have invested in developing a robust healthcare system, have leaderships that enjoy a high degree of trust, have been able to move swiftly, decisively and comprehensively once the crisis hit and have been clear and consistent in their messaging to their populations.

Painting the problem with broad brushstrokes by suggesting that one culture or political system is superior to others when it comes to handling the coronavirus misses the trees for the forest. Governments of the day must attend to the challenges posed by Covid-19 and do the best they can with imperfect and incomplete information.

After all, whether East or West, democracy or not, all governments have the same objective - which is to slow down the spread of the virus, maintain social order and get their economies back on track as quickly as possible.

WHY IT MATTERS

As global crises go, the situation we find ourselves in today with the coronavirus is eerily familiar.

In a sense, we've been there before with the severe acute respiratory syndrome, Ebola, the global food crisis and the global financial crisis - all recent crises of a transnational nature.

In times like these, we look to the great powers to transcend politics of strategic rivalry to lead a collective multilateral effort, harnessing knowledge and resources to bring them to bear against a common challenge.

In previous emergencies, the US and China managed to set aside their strategic rivalry and coordinate responses, in the process providing, in tandem, global leadership. Today, such coordinated leadership effort has been absent. Instead, great power politics has regrettably been allowed to frustrate hopes for much-needed international cooperation as leaders in Washington and Beijing prioritise domestic considerations and play to their respective domestic galleries. In Washington, a truculent narrative targeting China and laying blame for the virus on its shoulders continues to gather pace as the Trump administration stokes underlying nationalistic impulses, no doubt with an eye to the November elections, whilst at the same time distracting from its own struggle to contain the spread of the virus and the dire economic data that confronts it.

Furthermore, American insinuation of excessive Chinese influence on the World Health Organisation demonstrates that this rivalry also threatens to hold multilateral organisations hostage to great power politicking.

For its part, China has responded by parlaying a conspiracy theory of its own - that the coronavirus was planted by the US military.

Meanwhile, a sense of national pride and triumphalism has engulfed the country, but it masks concerns for the possibility of a new wave of infections and reliability of official data.

Having weathered the storm of the virus with discipline and sacrifice, not a few among the Chinese leadership feel that the country is well placed to anchor multilateral efforts to confront the crisis.

Without a doubt, China will play a crucial role in a global effort, not only through the resources it can muster but, equally important, through the sharing of knowledge on how the virus first originated and spread. Yet at the same time, Beijing's efforts to extend a helping hand to its neighbours and shift the coronavirus narrative in its favour have been undermined by its own recent adventurism in the contested waters of the South China Sea.

As the coronavirus pandemic continues its merciless spread across the globe, the need for cooperation, coordination and leadership is more urgent than ever.

Absent such a collective response, antithetical narratives that turn on simplistic caricatures driven by competition and rivalry are ultimately unproductive, futile exercises. They bring us no closer to a better understanding of and approach to dealing with the coronavirus today, or any other pandemic that may bedevil us tomorrow.

• Joseph Chinyong Liow is dean of the College of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences, Tan Kah Kee Chair in Comparative and International Politics, and professor at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University.