Up, up and away: How balloons help Singapore weather forecasting soar to new heights

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

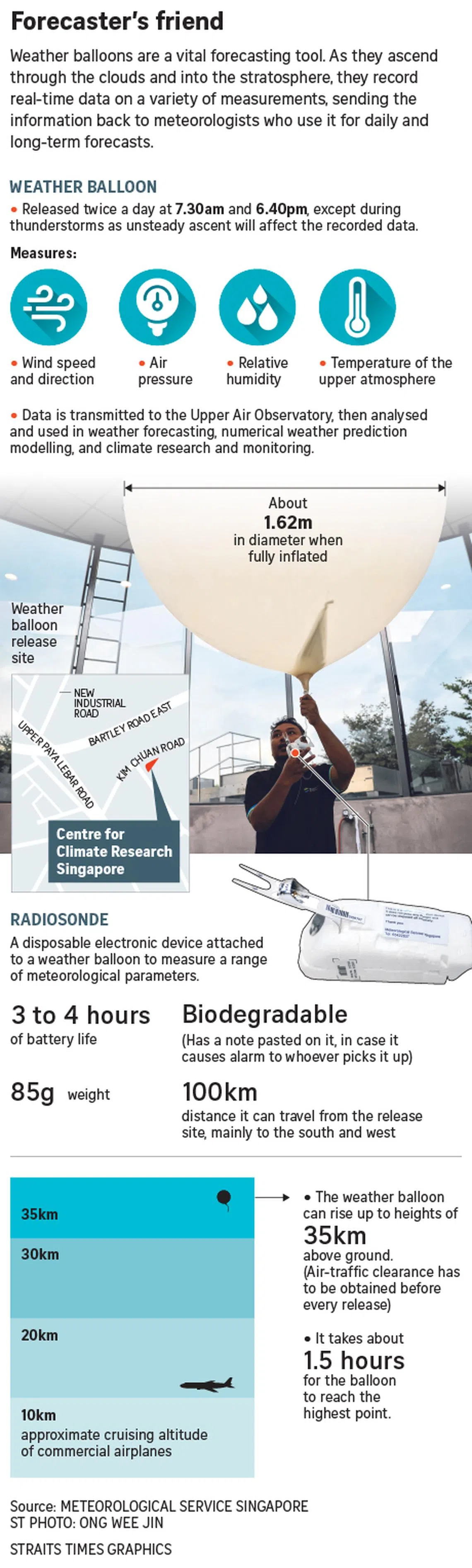

Weather balloons are released twice a day from the Upper Air Observatory at the Centre for Climate Research Singapore building in Paya Lebar.

ST PHOTO: ONG WEE JIN

SINGAPORE – Like a scene from a James Bond movie, the roof panel slides open to reveal the sky. But instead of a villain’s rocket blasting off from his lair, a weather balloon is released, quickly reaching the clouds above.

Like clockwork, weather balloons are released twice a day from the Upper Air Observatory at the Centre for Climate Research Singapore building in Paya Lebar, as part of the nation’s weather forecasting network. One is released around 7.30am and the other around 6.40pm, subject to clearance from Paya Lebar Air Base.

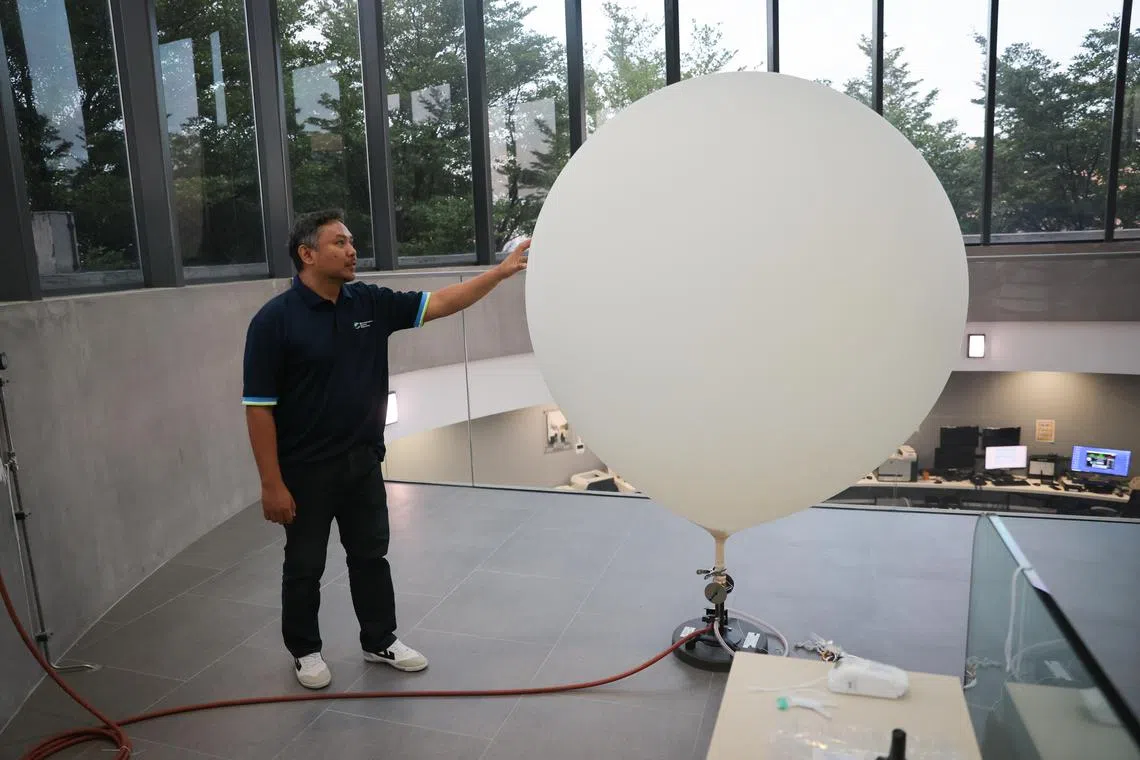

The balloons, about 1.6m wide and about the same height, carry small devices called radiosondes. Each balloon carries one. As the balloon ascends, the radiosonde records vital real-time data, such as temperature, wind speed, wind direction, humidity and air pressure that forecasters need to predict the weather.

The information is fed into a global database used by members of the United Nations World Meteorological Organisation (WMO) and researchers around the world, cementing Singapore’s key role in providing atmospheric data on the tropics, which are the world’s weather engine.

The balloons ascend to about 35km into the lower reaches of the stratosphere, sending data continuously back to the Meteorological Service Singapore (MSS), explained meteorologist Leong Pei Yi during a balloon release on Thursday morning.

Globally, balloons and radiosondes are used at hundreds of sites for weather forecasting.

The radiosonde Singapore uses has a battery that lasts three to four hours. Technicians can also track the device via global positioning system. And sometimes the radiosondes travel quite a distance – upwards of 100km from where they were released.

The $100 devices are designed to be disposable. The casing is biodegradeable, and so is the balloon.

What happens when the balloon reaches a height of 35km? It bursts, Ms Leong said, explaining that just before that happens, the balloon, which is made from natural rubber, would have swollen to between 6m and 8m wide. A small parachute inside helps the radiosonde, which weighs about 85g, gently fall back to the surface, taking weather measurements as it goes.

“Most of the time the radiosonde will drop into the sea around the Strait of Malacca as well as the Singapore Strait, so to our south and west. And sometimes they do land on mainland Singapore,” she said.

The data, combined with real-time measurements from ground stations and satellites, can help forecasters predict if the day will be stormy and when. And data on wind direction and speed is especially important in the tropics, since winds are one of the key drivers of local weather.

That is because in the tropics, there isn’t much temperature or air pressure variation.

“So most of our weather systems are driven by winds,” Ms Leong said.

By comparison, weather systems in the mid-latitudes are mainly driven by high- and low-pressure systems with large temperature differences. “So that’s why it’s very important for us to have radiosonde measurements,” she added.

The balloons, about 1.6m wide and about the same height, carry small devices called radiosondes.

ST PHOTO: ONG WEE JIN

The radiosonde is a disposable electronic device that measure a range of meteorological parameters.

ST PHOTO: ONG WEE JIN

MSS uses the data for daily and long-range forecasting. The data is also shared globally, and Malaysia and Indonesia also share their daily radiosonde data with Singapore to help the neighbours create more accurate forecasts.

“The radiosonde soundings are also used for climate monitoring. All the data we produce is very highly valued by the global research community. This is because our radiosonde observation was established back in 1953. So it has been operating for about 70 years.”

That makes Singapore one of the few stations in the equatorial region that has been operating for such a long period.

The Republic is also part of the Global Climate Observing System Upper Air Network, which is run by the WMO. There are about 170 stations in the network, and the main goal is to improve data collection for climate forecasts as well as climate change detection purposes.

And how will climate change affect forecasting?

“Climate change really exacerbates the challenges in weather forecasting in the tropics,” said Ms Leong.

That is because weather in the tropics is already inherently challenging because weather systems develop rapidly and can be very local, making them hard to capture in forecasting models.

“With climate change, it means there are variations in climate patterns. So that will definitely make the weather prediction more difficult. And with climate change, there’s also more extreme weather conditions that actually happen more frequently. So all of these extreme events are very difficult to predict,” she said.

Meanwhile, what happens to all those radiosondes? Most vanish without a trace.

“Sometimes when members of the public pick it up, they give us a call because the contact details are on the radiosonde, and they return it to us. But it’s quite rare,” Ms Leong said.