Doctors can bring in new US-approved drug for early-stage Alzheimer’s disease

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Some neurologists hail lecanemab as it is the first drug capable of slowing Alzheimer’s disease, giving patients more good years.

PHOTO: REUTERS

SINGAPORE – The United States earlier in July became the first country to approve a new drug called lecanemab, which has shown it can slow the progression of Alzheimer’s disease.

Although the drug has yet to be approved by local regulator, the Health Sciences Authority (HSA), its spokesman said doctors may request to bring in the drug, and two have already done so.

The US approval for the drug has some experts happy and others concerned.

Some neurologists hail lecanemab as it is the first drug capable of slowing the disease, giving patients more good years. Others point to the drug’s small gains – it slows but does not even halve the progression of the disease – against its potential risks, including death. Studies showed it slowed the progression of the disease by 27 per cent over 18 months.

The HSA told The Straits Times that doctors who want to use it for their patients can bring lecanemab in on a named patient basis.

“Where there is an unmet medical need, clinicians may exercise professional judgment and apply to the HSA via the special access route to bring in an unregistered therapeutic product for use on patients under their care, if clinically justified,” HSA said. It has already approved two applications by clinicians to bring the drug in via this route.

Lecanemab, which costs about US$26,500 (S$35,200) a year in the US, and is administered as an intravenous infusion every fortnight, carries a “black box” warning highlighting the major risks. It should not be used by patients on blood thinners, those having clotting disorders or seizures, or those who had a stroke.

Associate Professor Adeline Ng, a senior neurologist at the National Neuroscience Institute, calls the drug a “positive step forward in the treatment of dementia”, as current treatments are able to treat only the symptoms such as language difficulties, sleep disturbances or poor attention.

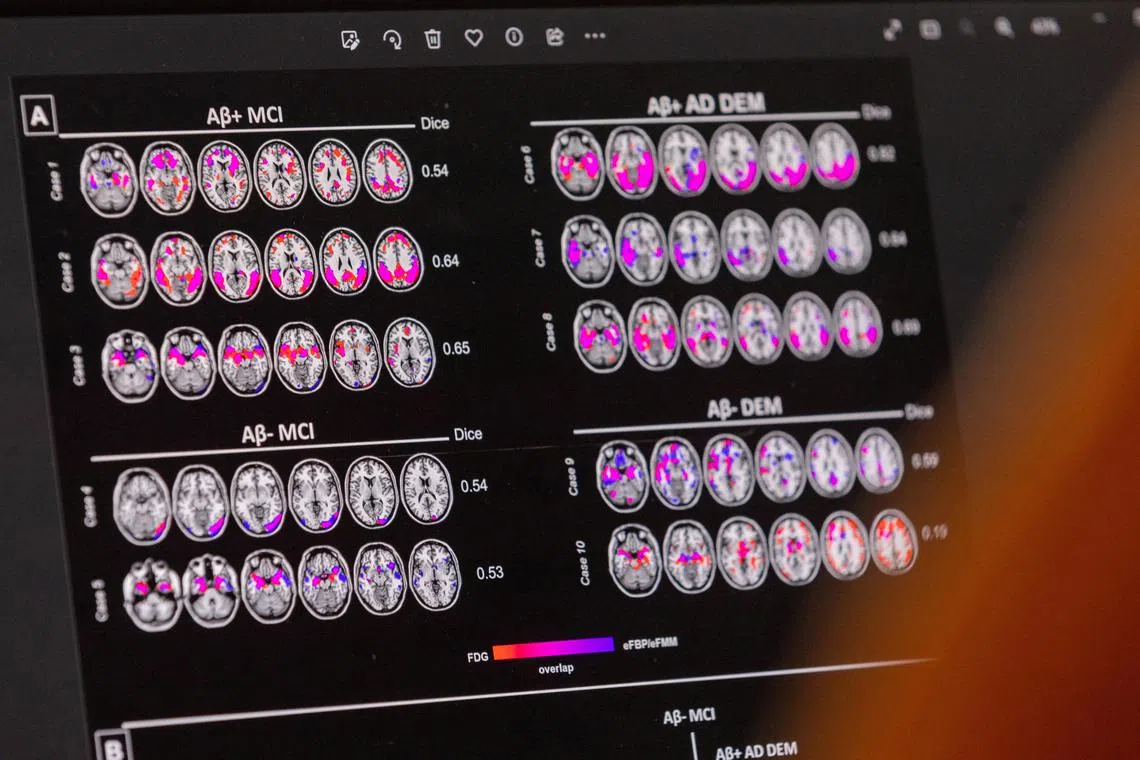

She said: “Lecanemab removes beta-amyloid plaques from the brain, and this has been shown to reduce cognitive decline in people with mild cognitive impairment (pre-dementia) or in early stages of Alzheimer’s disease with mild symptoms.”

Beta-amyloid plaques, she explained, are a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease. They are tangles of protein that form at the junction of nerve cells, thereby disrupting the flow of information in the brain.

Most dementia patients here are diagnosed at age 65 years and older, with three out of five suffering from Alzheimer’s, one of several forms of dementia. Other forms include vascular dementia and fronto-temporal dementia.

Lecanemab is effective only for those with Alzheimer’s.

An estimated 80,000 people here have dementia, with the number expected to increase to 100,000 by 2030. Aside from memory loss, dementia can cause personality changes, poor time management and language problems.

Prof Ng added: “It is a chronic condition that gets worse over time, increasingly affecting a person’s ability to think and function, resulting in loss of independence until they are fully dependent on care.”

Associate Professor Christopher Chen, director of the Memory, Ageing and Cognition Centre at the National University Health System, said: “Alzheimer’s disease is devastating for patients and their families, hence a treatment that is effective and safe in delaying progression would be most welcome.”

He was involved in the global clinical trial of lecanemab where 1,795 patients were given the drug or a placebo over 18 months. Among them were 13 patients from the National University Hospital (NUH).

In a statement by NUH in December 2022, Prof Chen said: “What we want to do for Alzheimer’s patients is to slow or even halt the progression of their disease, so that it is possible for them to enjoy a good quality of life whilst living with Alzheimer’s for many years.”

Dr Tauqeer Ahmad, a neurologist at Gleneagles Hospital, is just as enthusiastic about lecanemab, as there is currently no “definite treatment” for the debilitating disease.

“Yes, we as neurologists are very excited with the new drug coming in to the market,” he said. The disease can progress quite quickly, he said, in a matter of six to 12 months.

Correction note: An earlier version of this story said three NUH patients participated in the global clinical trial of lecanemab. This has been corrected to 13.