He was gripped by fear as he watched one of his uncles stab their brother over a trivial matter. He was just seven years old then.

Violence at home soon became routine. It would be normalised in his adulthood. And it would strain his marriage.

“I never really listened to my wife,” acknowledges Mr Sebastian Sasikumar, 39, who has been married since 2009. The father-of-four describes a tense relationship; communication was often difficult. Impatient, he would respond with anger.

Even two close calls with death, one leaving a large visible scar on his neck, failed to crack his wall of emotions. “My wife was there with me through it all,” he says, “but I was blind to her love.”

Today, a different man sits across the table. Mr Sasikumar, who works as a trailer driver, is calm and relaxed. He answers questions with a disarming openness that belies his violent past; he would often punctuate his responses with easy laughter.

The change is clear. “I could sense that Sebastian is different,” says Mr Haridas Patrick, 42, who first met Mr Sasikumar when they were in their 20s. They lost touch along the way and only reconnected last year.

“The Sebastian I knew had no patience. He was the first guy to say something to your face with no filter.” Mr Patrick adds with a laugh: “This time round, his aura is different. He’s smiling a lot.”

Surprised by his friend’s change in temperament, he was curious: What brought about this transformation?

Family, says Mr Sasikumar. Beyond his wife and children, “family” also includes more than 80 “brothers” now in his life.

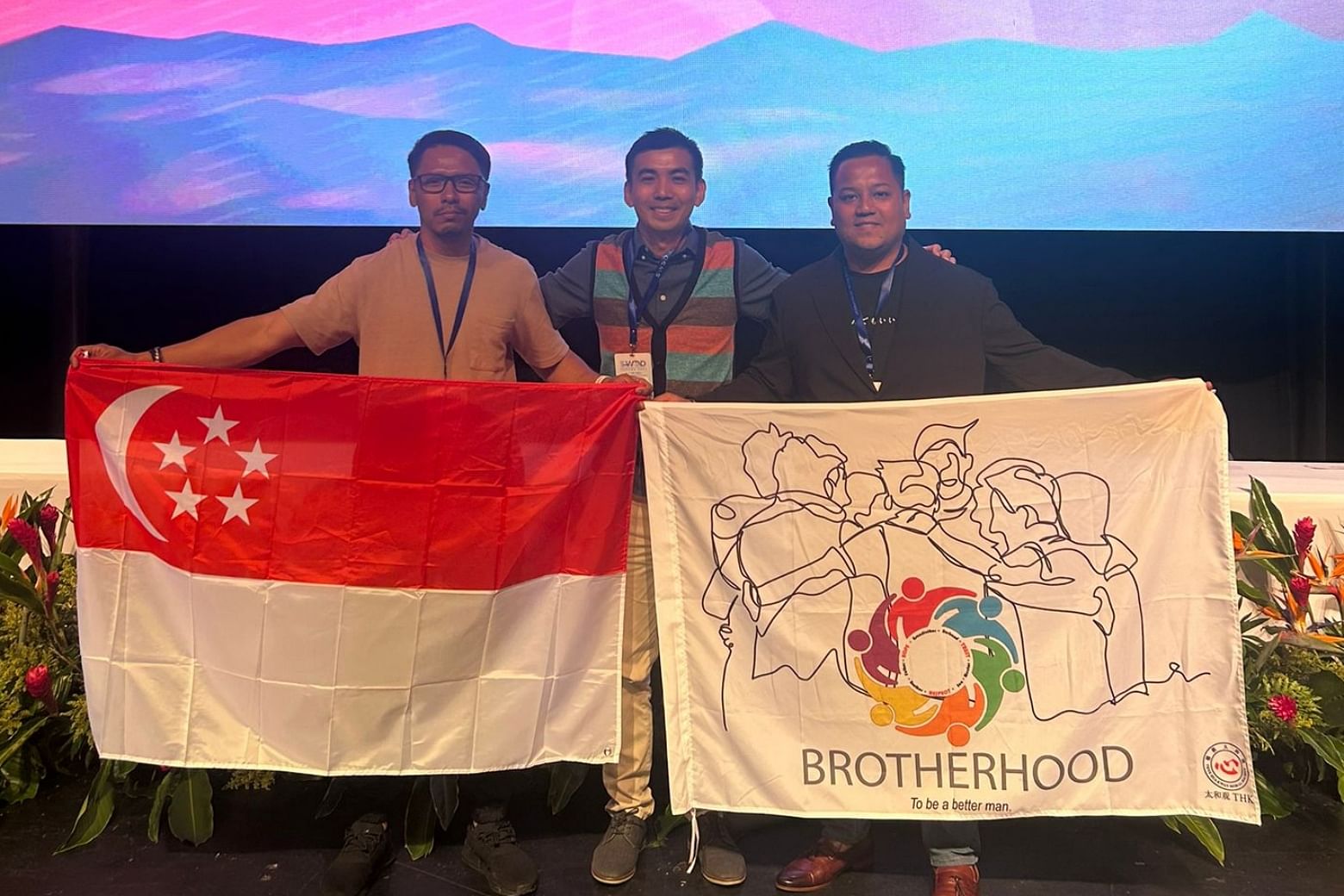

Mr Sasikumar is part of the Brotherhood programme, run by Thye Hua Kwan Moral Charities. The healing initiative, launched in 2019, supports men who struggle with violence.

Growing up

The programme aims to break the intergenerational cycle of violence, says Mr Ben Ang, principal social worker at Thye Hua Kwan Family Services.

“We believe everyone suffers – not just people who have been hurt, but also those who have hurt others,” says Mr Ang, 42. “So we want to support them in healing.”

Mr Sasikumar recalls how, when he was younger, violence was normalised in his family. “My uncles settled problems among themselves using violence,” he says. “Why did it have to be like that? Why were they always in and out of prison? I didn’t know.”

His growing-up environment provided no answers. His father died when he was one, and his mother and elder brother worked long hours to support the family. “I mixed with the wrong company,” says Mr Sasikumar, “and they taught me that sometimes, violence is good.

“I started to think of violence as the only way to handle a situation.”

This early exposure to violence devolved into a volatile adulthood. His explosive nature led to frequent clashes with his stepfather and elder brother.

His mother pleaded with him to control his temper, but his rage drove a wedge between them. “My mother stopped talking to me for 24 years,” says Mr Sasikumar.

Things came to a head in 2016 when one of his sons died. He was devastated. It was an episode that he does not want to revisit. He didn’t know how to process the grief, and resorted to the only way he knew: Anger and violence.

More trauma ensued. Frustrated with his behaviour, his wife took their kids to stay at a shelter – one of 10 times she felt compelled to leave.

“I cried every day,” he says with a shaky voice, recalling how he was suddenly alone in their one-room rental flat.

“My wife went to stay at the shelter to let me know of her importance,” says Mr Sasikumar. “It took me 10 times to learn. I kept thinking: ‘Why does she keep going to the shelter?’” His wife and kids have since moved back home.

Finding hope

After three decades of soul-searching, he finally found answers in the Brotherhood programme with the help of his counsellor. Each run of the programme has eight to 10 sessions, held on Saturday afternoons at Thye Hua Kwan’s family service centre in Bedok North.

The sessions, which are facilitated by social workers like Mr Ang, are held once every three weeks. Participants, who are formerly violent men, tend to come from troubled backgrounds.

“Brotherhood made me understand how important my wife and kids are. It taught me how to correct my mistakes and be a better man.”

He adds: “Nobody (in the Brotherhood programme) penalises you for what you’ve done. They don’t say ‘Look Sebastian, that’s wrong!’ But they make you think, and then you’ll realise you were wrong.”

During the sessions, participants are also free to share their problems and learn from each other’s experiences. Mr Sasikumar and his wife now take a timeout whenever they are angry, resuming the conversation with cooler heads – a coping strategy that he learnt from the programme.

Mr Sasikumar is slowly making peace with his past and rebuilding his life. His relationship with his family, now based on open communication and mutual respect, has never been stronger, he says.

He has also made amends with his mother and is learning to forgive himself. “I still carry some pain with me, of course,” he admits, “but I'm learning.”

Their relationship has improved. Recalling the tearful reunion with his mother in 2022, he says: “I cried. I laid down and touched her feet. I said, ‘I am really sorry, I didn't know that you were working so hard for us and I hurt you so much with my words and my actions’.

“I was so ashamed.”

He likens his journey to kintsugi, the Japanese art of repairing broken pottery with gold. During one of the sessions, participants were given glass cups to break and repair.

“I learnt you can still put the cup back if you are patient,” he reflects, sharing how they had to painstakingly find and pick up the pieces to mend the cups. In the same vein, “take time to say sorry, and take time to forgive yourself”.

“The scars will be there, but that’s okay. The cups can be put back together.”

Mr Sasikumar speaks openly about his past struggles because he wants other men to know there is hope: “If there’s a problem, there’s a solution. You just need the right ‘tools’: Forgiveness, patience, and love.”

Ending the cycle of violence

Launched in 2019 by Thye Hua Kwan Moral Charities, the Brotherhood programme tackles domestic violence at its core – by helping men heal from past trauma and break the cycle of violence.

The programme offers a three-pronged approach: Discovering your values, analysing your behaviour, and finding forgiveness. But the real power lies in its long-term impact, says Thye Hua Kwan’s Mr Ben Ang.

Mr Ang estimates that about 80 to 90 per cent of the 80 men who have benefited from the programme come from violent backgrounds. He explains: “Children who have been brought up in a violent family environment have a higher chance of being violent or becoming a victim of family violence.”

“A lot of intervention in the field is about ensuring safety for people who are in the cycle of violence, which is very important,” he says. “But we need to dig deeper to solve the root cause of family violence too.”

By reaching out to men who were violent, and fostering positive change, the programme creates a ripple effect. Children witnessing their fathers’ transformation learn healthier ways to manage anger. Wives who have been harmed find a path to healing.

That’s the idea behind the “Brotherhood” name as well. “We want to partner these men to be part of the solution to end family violence,” says Mr Ang, who has been a social worker for 16 years.

Mr Sebastian Sasikumar embodies this shift: “We’re very open and we talk things out in front of our kids. I want them to know what is happening with us, so next time when they become parents, they know what to do and how to handle such situations.”

“I want them to learn all these things that I never learnt when I was young.”

Part of the programme is also about shifting perceptions. For sustained change, says Mr Ang, they need to be empowered and change how they see themselves – no longer the perpetrator, but an agent of change.

Brotherhood fosters a sense of community, with outreach programmes, peer mentorship, and opportunities for upskilling.

Mr Sasikumar mentors his friend Mr Haridas Patrick. Inspired by the Brotherhood’s positive impact on Mr Sasikumar, he joined the programme last July.

Mr Patrick, who is married and has a daughter, shares: “Previously, I was very egotistical, always needing to have the last word.” And when the couple fights, he would “sometimes use abusive language”.

Now, he prioritises healthy communication. “I tell my wife I need to step away when I’m angry, so I can talk to her in a better way and not regret my words after.”

“Brotherhood is my school,” says Mr Sasikumar, “I learnt everything here, and that’s why I’m committed to giving back.”

Break the Silence

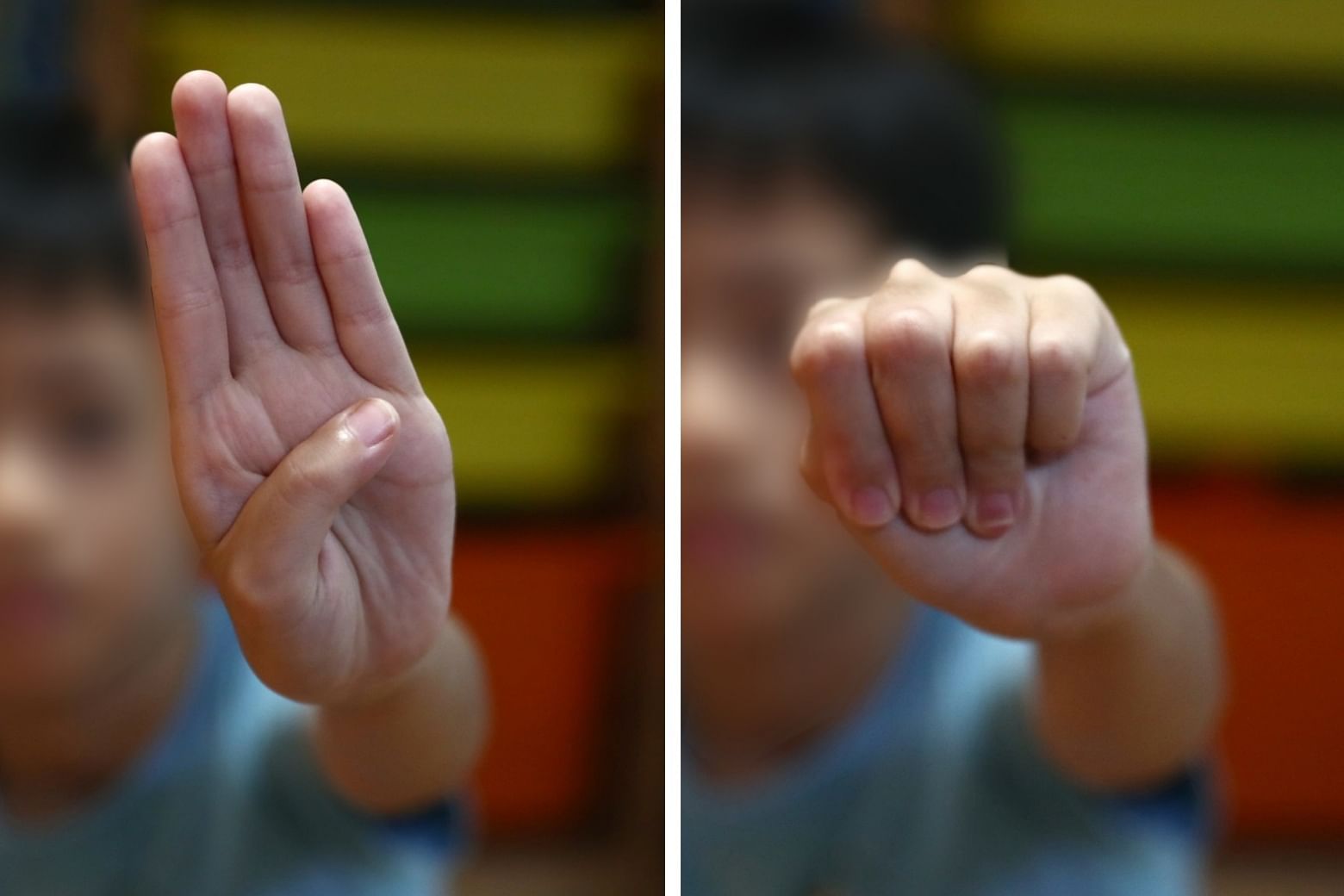

Break the Silence is an ongoing campaign by the Ministry of Social and Family Development that aims to raise public awareness of domestic violence.

The campaign’s logo is the Signal for Help gesture – a non-verbal cue that victims can discreetly use to get help.

What to do if you spot the signal:

- Be discreet as you try to help the victim. Do not respond immediately to avoid alerting the perpetrator, who may be nearby

- Avoid direct confrontation with the perpetrator unless necessary, as it may potentially escalate the situation

- If possible, reach out to the victim using another form of communication, such as through text messages or social media

- Ask the victim “yes” or “no” questions to reduce risk and make it easier for them to respond. For example, you can ask if they need help or if you should call the police

In partnership with the Ministry of Social and Family Development