BRANDED CONTENT

How to tell if someone is suffering abuse? Here are some signs, and what you can do

Bystanders play a key role in stopping domestic violence, but some may fear retaliation or being seen as “nosy”

It's important for bystanders to listen without judgement, and remind domestic violence victims that it was not their fault.

PHOTO: GETTY IMAGES

Genevieve Chan, Content STudio

Follow topic:

The woman, in her 40s, could often be seen standing silently outside her home with her head bowed, eyes down for hours on end.

She would appear withdrawn, and would not make eye contact with anyone. Neighbours in her Housing Board block also detected a strange odour every time they walked past her.

She had no visible bruises or injuries, a common indicator of abuse. Still, neighbours could not shake off a foreboding sense of unease.

They called the police.

They were right to act. Subsequent investigations revealed that Mdm K, a foreigner, was being abused by her mother-in-law. She was given only one slice of bread and a bowl of white rice to eat a day, and allowed to shower once every two to three weeks.

Reflecting on the case, Mr Martin Chok, deputy director of non-profit organisation Care Corner Project StART, says: “Bystander intervention disrupts the cycle of abuse. It sends a clear message that such behaviour is not acceptable nor tolerable.”

Care Corner Project StART is a protection specialist centre that provides integrated services for individuals and families affected by family violence and sexual assault.

Domestic violence refers to patterns of violent, threatening, abusive or controlling behaviours that leave victims feeling unsafe and fearful. It can take on many forms including physical, sexual, emotional and psychological abuse, and neglect.

Domestic violence can occur in families, households, current or past intimate relationships.

Empowering survivors

- Home away from an abusive home: This Singapore shelter, which keeps its location confidential for the safety of its residents, is helping domestic violence survivors rebuild their lives with greater confidence.

- Expanding protection: Family violence legislation in Singapore has been strengthened to better protect survivors and hold perpetrators accountable. Learn more about the changes here.

The National Anti-Violence and Sexual Harassment helpline received 10,800 calls in 2022, up from 8,400 in 2021. About 3,000 of these calls per year were inquiries related to abuse or violence, according to the Ministry of Social and Family Development.

Why you should step up

Despite the importance of bystander intervention, some may still hesitate to take action. Mr Chok, 46, who has over two decades of experience in social work, observes that one of the most common reasons is the fear of retaliation from the perpetrator, either towards the bystanders or the victim.

“This is a valid concern, and bystanders should ensure that they do not get hurt in the process of offering help,” says Mr Chok.

Be sure that you’re in a safe place before calling for help, or reach out to the victim when the perpetrator is not around. “You may not want to call the police in front of the perpetrator when there’s a quarrel or a fight going on,” he says.

Another common reason is the belief that “this is a family matter, and we should let the family settle this on their own”, says Mr Chok. “People don't want to be perceived as being nosy for intervening.”

Those who are related to the perpetrator may also think that the perpetrator can change, says Mr Chok, or that they might affect that person’s future by making a report.

But “if you make a report, the police can intervene and the cycle of abuse can be broken”, he says.

Care Corner Project StART works with the police and other community partners to support domestic violence survivors. It offers various forms of support, including addressing the victim’s practical needs like accommodation, providing counselling, and running support group sessions.

It also works with individuals who have caused hurt to their family, to help them move forward without violence.

Ms Rachel Phay, 30, who works in a trade association, is one who is willing to step up. “Of course we must report incidents of violence that we see,” she says. “It is merely about showing empathy and neighbourly concern.”

She doesn’t care about being perceived as a “busybody”. “In matters of life and death, why worry about coming across as nosy?”

Mr Chok hopes such sentiments will prevail: “Do not be afraid that you might be meddling in other people’s issues. By speaking out for them, you can help save someone from abuse and make a difference to their life.”

In Mdm K’s case, that call from neighbours saved her from further starvation and suffering.

Mdm K, reports a heartened Mr Chok, is doing well. After the investigation, she moved out of her abusive home and into a crisis shelter. Care Corner supported her in her recovery, which took six years.

How to tell when all’s not well

You need to pay close attention to subtle cues and behavioural patterns, says Mr Chok, to discern less visible forms of domestic violence like emotional and psychological abuse.

He shares some common signs of abuse:

- Physical: Injuries and changes in sleeping or eating habits

- Psychological: Hypervigilance, increased anxiety and constant fear

- Emotional: Lowered self-esteem, suicidal thoughts, self-harming behaviour and self-blame

- Social: Withdrawal from social interactions and isolation

Ms Chong Shi Lin, 33, a business manager, is sure that she will report incidents of domestic violence if it occurs to someone she knows. But she is unclear about what to do when it comes to strangers, and how to best recognise domestic violence.

“If I report it, will I need to provide evidence? Will my words be taken into consideration?”

How can you tell if it is just a normal argument or a potentially abusive situation if you’re a stranger?

Mr Chok’s advice: Trust your instincts and remain attentive to potential signs of abuse, no matter how subtle they may seem. If physical violence, threats, or other forms of aggression are involved, calling the police can help ensure the safety of the victim and hold the perpetrator accountable, he says.

Mr Chok says some warning signs include:

- How quickly the argument escalates

- The appearance of fear or submission

- Any form of physical aggression

- The distress caused to others nearby

“Even if you’re unsure of the full situation, taking action can prevent the situation from escalating and potentially save lives.”

He recalls an incident where a victim in her 20s, who was about 6 months pregnant, was seen being scolded by a man she was with at the bus stop. “A young girl noticed that the victim appeared sad, and could see the intimidating body language of the perpetrator, who was sneering at the victim with clenched fists,” he says.

When the perpetrator left, the girl approached the victim to ask if she needed help. They called the police, and the victim was referred to Care Corner Project StART. She applied for a personal protection order against the perpetrator and left the abusive home.

What you can do if you’re a victim

Deciding to seek help can be challenging. Fear of retaliation, concerns about the future, and uncertainty are all common emotions for survivors.

It is important to remember that you are not alone. Trained professionals can listen confidentially and provide support.

If you or someone you know is experiencing domestic violence, you can:

- Contact the National Anti-Violence and Sexual Harassment Helpline (NAVH) by calling 1800-777-0000 or submitting an online report at go.gov.sg/navh

- In case of immediate danger, call the police at 999 or send an SMS to 71999

Break the Silence

Break the Silence is an ongoing campaign by the Ministry of Social and Family Development that aims to raise public awareness of domestic violence.

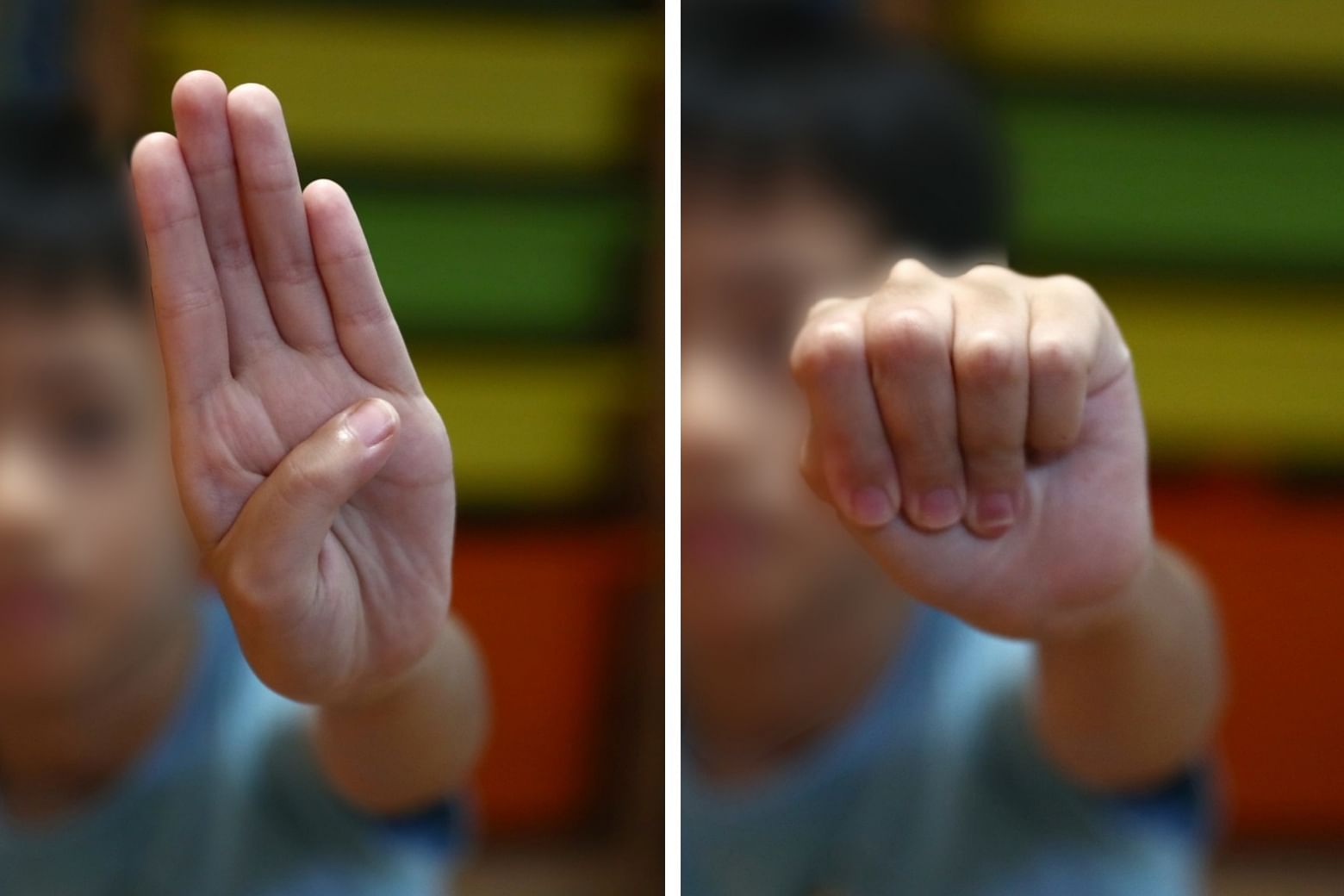

The campaign’s logo is the Signal for Help gesture – a non-verbal cue that victims can discreetly use to get help.

What to do if you spot the signal:

- Be discreet as you try to help the victim. Do not respond immediately to avoid alerting the perpetrator, who may be nearby

- If possible, reach out to the victim using another form of communication, such as through text messages or social media

- Ask the victim “yes” or “no” questions to reduce risk and make it easier for them to respond. For example, you can ask if they need help or if you should call the police

In partnership with the Ministry of Social and Family Development