11 soccer pitches a minute – rate of tropical rainforest loss in 2022: Study

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

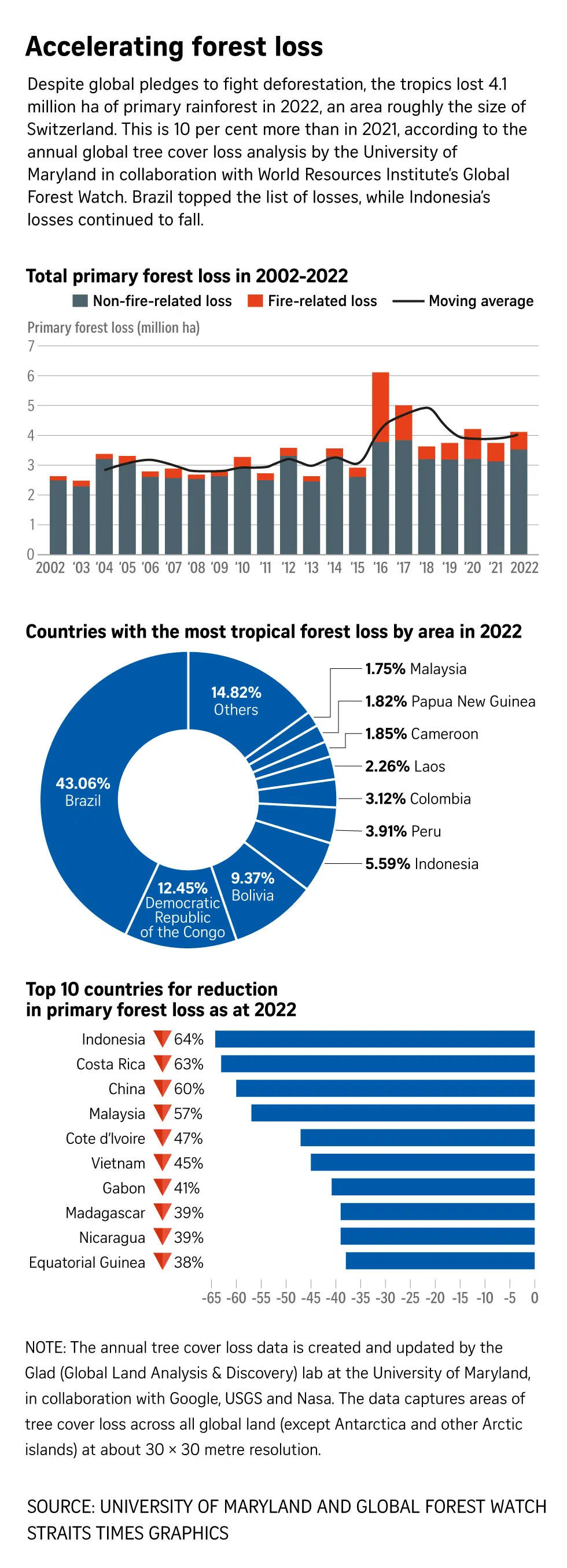

Forest loss was highest in Brazil, Bolivia and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

PHOTO: REUTERS

SINGAPORE - Despite global pledges to tackle deforestation, the tropics lost 10 per cent more primary rainforest in 2022 than in 2021, the equivalent of 11 soccer pitches of forest disappearing per minute, a global analysis released on Tuesday showed.

Tropical primary forest loss totalled 4.1 million ha, an area about the size of Switzerland, according to the analysis of 2022 tree cover loss data.

The study, which is based on satellite measurements, is a collaboration between the University of Maryland and the World Resources Institute’s (WRI) Global Forest Watch.

Forest loss was highest in Brazil,

Globally, the tropics are losing forests faster than anywhere else, mainly for agriculture, timber and mining.

This is a concern as tropical rainforests are huge stores of biodiversity and soak up vast amounts of carbon dioxide (CO2), the main greenhouse gas. These forests also regulate local and regional climates, storing large amounts of water that can help generate rainfall.

Chopping down forests can raise local temperatures, exacerbate drought and release large amounts of CO2.

Fires, lit deliberately or caused naturally, are also a major source of forest loss and emissions.

“That loss (in 2022) resulted in the emissions of 2.7 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide emissions, which is equivalent to the fossil fuel emissions of India,” said Ms Mikaela Weisse, the director of Global Forest Watch, an online data platform.

“Since the turn of the century, we have seen a haemorrhaging of some of the world’s most important forest ecosystems, despite years of efforts to turn that trend around,” she told a media briefing.

“This year’s data shows that we are rapidly losing one of our most effective tools for combating climate change, protecting biodiversity and supporting the health and livelihoods of millions of people,” she added.

At the United Nations’ COP26 climate talks in Glasgow in 2021, more than 140 nations, including Singapore, signed the Glasgow Leaders’ Declaration on Forests and Land Use, to halt and reverse forest loss and land degradation by 2030.

Mr Rod Taylor, global director of forests at WRI, a Washington-based think-tank, said: “Are we on track to halt deforestation by 2030? The short answer is no.”

In 2022, Brazil lost nearly 1.8 million ha of primary forest – defined as mature forests that have not been cleared or regrown in recent history.

Of this amount, it lost 1.42 million ha to non-fire causes, up 20 per cent from 2021, and 344,064ha to fires, a small drop from 2021.

Fires are a major and growing source of forest loss in the tropics and elsewhere as global temperatures rise and droughts become more severe.

In 2015, fires devastated large areas of Indonesia. The following year, Brazil lost 1.6 million ha due to fires.

In 2022, Russia lost 4.3 million ha of tree cover, of which 73 per cent was fire-related.

Smoke from fires can trigger widespread health impacts across borders, pointing to the current wildfire crisis in Canada.

PHOTO: NYTIMES

Elsewhere in 2022, Bolivia lost nearly 400,000ha of primary forest – the highest year on record for the country, largely due to clearing for agriculture.

The Democratic Republic of Congo lost just over 510,000ha, similar to levels of the past few years.

Ghana in West Africa recorded the biggest increase in primary forest loss of any country in recent years, up nearly 70 per cent from 2021 to 2022, due largely to agriculture.

But the loss at nearly 18,000ha is small in comparison to elsewhere in the world, the study notes.

Earlier in June, the chief executive of Temasek-owned investment firm GenZero, Mr Frederick Teo, said the company had recently signed a memorandum of understanding with carbon project developer AJA Climate Solutions to restore about 100,000ha of degraded land in the Kwahu region of Ghana.

Indonesia’s primary forest loss increased 13.3 per cent to 230,000ha compared with 2021, but overall the trend was tracking near the record lows of recent years.

It is a similar picture with Malaysia, which lost about 72,000ha, far below the peak levels of the past.

Ms Frances Seymour, a distinguished senior fellow for forests at WRI, said the findings of the analysis were alarming.

“One thing is clear. What happens in the forest doesn’t stay in the forest,” she told the briefing. “Trade in wildlife can spread viruses that cause pandemic outbreaks in cities. Irresponsible mining can contaminate rivers downstream.”

Flames reach upwards along the edge of a wildfire as seen from a Canadian Forces helicopter surveying the area near Mistissini, Quebec, Canada, on June 12, 2023.

PHOTO: REUTERS

Smoke from fires can trigger widespread health impacts across borders, she said, pointing to the current wildfire crisis in Canada.

But there were some reasons for hope, Ms Seymour said.

A global deal that set new 2030 targets to protect biodiversity, agreed at a major UN conference in Montreal in late 2022, could direct more financing to protect forests and restore degraded areas.

The new administration in Brazil has committed to reduce deforestation in the Amazon and for other vulnerable ecosystems.

The new World Bank president, Mr Ajay Banga, could also mobilise considerable resources to support countries to integrate forest protection and restoration, Ms Seymour added.

“It’s time to double down on these opportunities because time is running out,” she said.