Get hands-on in an artisanal journey through Kyoto and Osaka

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Kintsugi experience at Heiando in Kyoto, which is run by master Hiroki Kiyokawa.

PHOTO: COURTESY OF ROKU KYOTO

KYOTO/OSAKA – Enrich your jaunt to western Japan by interacting with artisans and experiencing the historical craftsmanship of Kyoto and Osaka.

These can be arranged by the concierge during your stay at Roku Kyoto: LXR Hotels & Resorts and Conrad Osaka, both of which are managed by Hilton.

Porcelain-making (togei)

Mark your stay at Roku Kyoto with kiln-fired ceramic art, crafted under the guidance of third-generation porcelain master Kano Shokoku.

Moulded into your unique piece of pottery is soil that was extracted from the Roku Kyoto estate during the construction process. This means you can take home a slice of history.

Roku Kyoto, flanked by the Takagamine mountains and situated along the Tenjin River, is located on land where the 16th-century calligrapher and craftsman Honami Koetsu once built an artists’ village.

Visit the atelier of the 75-year-old master, whose actual name is Michio Kano, but adopted his grandfather’s “Kano Shokoku” name after his father died in 2000. This is customary for traditional Japanese craft businesses.

The third-generation Kano Shokoku, whose actual name is Michio Kano.

PHOTO: YUMA HASHIMOTO FOR THE STRAITS TIMES

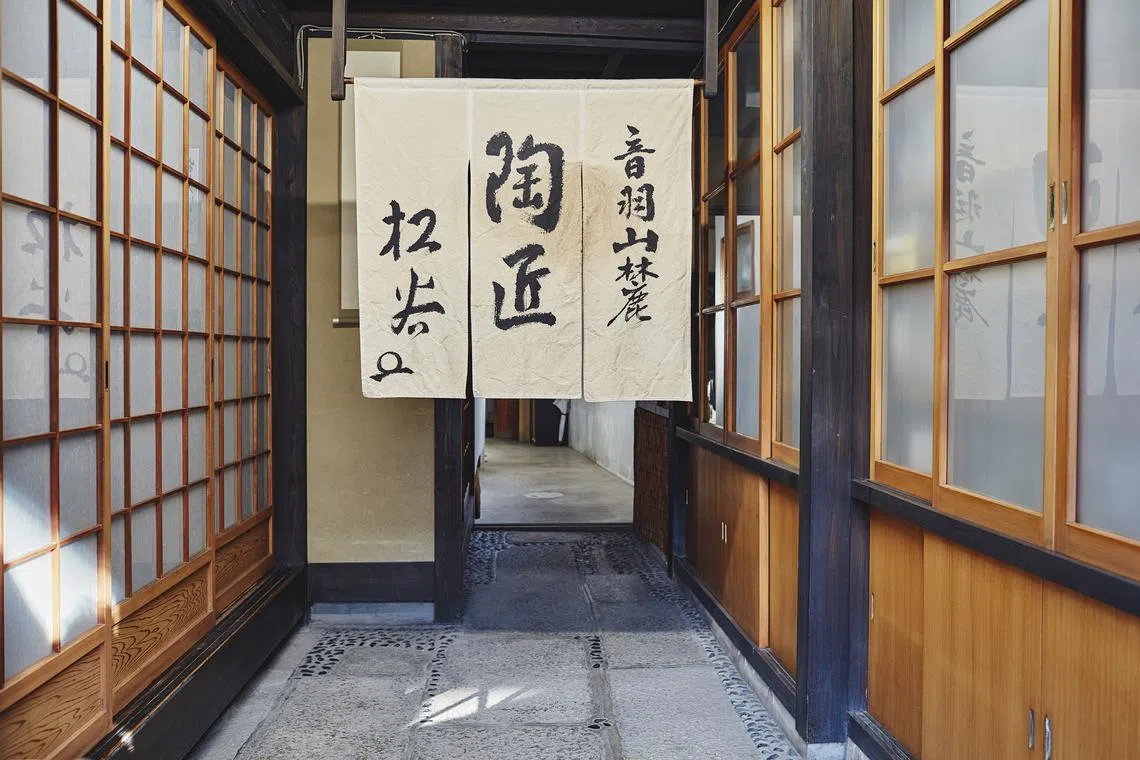

His nondescript studio is marked by a barely noticeable sign at the door and then a noren curtain as you enter.

Shelves of porcelain in different intricate shapes, patterns and designs are on display. These include saucers, bowls, plates, teapots and even a multi-tiered afternoon tea set shaped like a Christmas tree.

One shot glass, Kano says, was built using sand from Mont-Saint-Michel in France.

The noren traditional Japanese curtain at the entrance of Kano Shokoku’s studio in Kyoto.

PHOTO: ROKU KYOTO

There is no one better to learn the history of Kyoto porcelain from than the master, who explains how pottery has changed with the times and the meaning behind motifs such as pine, which is a symbol of Japanese longevity.

“In the old days, there were fewer varieties of food, and so the bowls used in kaiseki (a traditional multi-course meal) were bigger,” he says. “Now, instead of seven dishes, there are 13 or 14 dishes, and so the vessels are getting smaller.”

The porcelain work by this reporter is delivered to his home after three months.

ST PHOTO: WALTER SIM

Then, create your own piece of porcelain. I make a leaf-shaped saucer, imprinting on it Roku Kyoto’s seal, before it is fired at the Shokoku kiln – one of Kyoto’s most famous – and then delivered to my home three months later.

Kano, who is also director of the Kyoto Ceramic Art Association and has exhibited his works nationwide, is passing on the business to his second son Tomoo, who will eventually take on the “Kano Shokoku” name as the fourth generation.

Where: 591 Jihoin Anmachi, Higashiyama-ku, Kyoto, 605-0871 Japan www.shoukokugama.com

Cost: 26,000 yen (S$260) a person (arranged via Roku Kyoto)

Duration: Two hours

Info:

Kintsugi

Discover the ancient art of kintsugi, the Japanese craft of repairing broken, chipped or cracked ceramic pieces with lacquer and gold, at the Heiando atelier run by craftsman Hiroki Kiyokawa.

The 66-year-old master of lacquer restoration art had apprenticed under the best of craftsmen to inherit traditional techniques from the Edo period (1603 to 1867), and has showcased his work abroad, including in Rome and the Vatican City.

Kintsugi master Hiroki Kiyokawa.

PHOTO: YUMA HASHIMOTO FOR THE STRAITS TIMES

The idea behind kintsugi is akin to the Japanese philosophy of wabi-sabi, or the embrace of imperfections and flaws. Cracks and chips are not hidden in the kintsugi process.

The method of using lacquer to fix pottery has been found in archaeological excavations of earthenware dated to the Jomon period 6,000 years ago.

Kiyokawa, who has more than four decades of experience in the restoration of Buddhist statues, ceramics, lacquerware and antiques, is one of the most acclaimed in his field.

“Kintsugi restoration gives birth not just to the repaired vessel, but also to a new form of beauty by accentuating and celebrating imperfections,” he says.

While it is now possible to use chemicals, he insists on the age-honoured tradition of using natural sap collected from lacquer trees. The fact that such restored vessels have lasted centuries is proof of their durability, he says.

Learn the ropes from Kiyokawa himself at his studio overlooking the east gate of Kyoto’s Daitokuji Temple.

While kintsugi gets its name from how gold (kin) is typically used in the decoration, other materials such as platinum powder, silver powder, raden seashell inlay and coloured lacquer may also be used.

After a brief lecture on the history of kintsugi, the studio will provide a piece of pottery for restoration in the hands-on experience, where visitors can try the final steps of applying gold.

Kintsugi work by this reporter.

ST PHOTO: WALTER SIM

This is because the earlier steps of glueing the broken pottery using nori-urushi (a material mixed with rice flour and lacquer) as a base coating, and then filled with sabi-urushi (a mixture of powdery mountain clay, lacquer and water), take weeks to dry and finish.

The lacquer coating of the cup I restore is left to harden in a muro (curing box), and later delivered to my home.

“Breakage should not be seen as negative, because everything is destined to break some day,” Kiyokawa says. “Kintsugi gives things a new lease of life, and is a metaphor for building a new future.”

Where: 14 Murasakino Monzen-cho, Kita-ku, Kyoto, 603-8216 Japan www.heiando-kyoto.com

Cost: 20,000 yen a person (arranged by Roku Kyoto)

Duration: Two hours

Info:

Tea ceremony (Chado)

Learn the intricacies of the Japanese way of tea by taking part in a traditional Japanese tea ceremony – known as chado or sado – led by tea master Randy Channell Soei.

The Canadian chado master is from the Urasenke school, one of the main schools of Japanese tea ceremony. He will provide guests of Roku Kyoto with an authentic experience at the historically significant Hogyoku-tei guesthouse, located in a nearby lush Japanese garden.

Chado with tea master Randy Channell Soei of the Urasenke school of tea.

PHOTO: ROKU KYOTO

A resident of Kyoto for more than three decades, Channell teaches chado at the Nashinoki Shrine on the east side of the Kyoto Imperial Palace. In 2023, he was appointed to the council of the Japanese Cultural Affairs Office.

Channell introduces Japanese aesthetics and basic points of etiquette during an exclusive tea ceremony. After trying my hand at preparing tea, I realise how exacting an art form it is.

I sit in the seiza position, or the formal Japanese style of kneeling, as I learn about how tea cups are passed from tea master to their guests, who are central to the tea ceremony. Channell says: “If there are no guests, there is no way of tea.”

He left Canada for Hong Kong in 1977, where he studied gongfu and learnt of the Japanese spirit of bunburyodo, or the idea that a warrior should be accomplished in both martial and cultural arts.

He moved to Japan in 1985, and then to Kyoto in 1993 to study at the prestigious Urasenke Gakuen Professional College of Chado. Over three years, he learnt the history behind the tea ceremony as well as the practical skills needed to become a tea master.

“Soei” is Channell’s honorary tea name, or chamei, which he was bestowed with in 1999 by the 15th Urasenke Grand Tea Master.

Chado with tea master Randy Channell Soei, of the Urasenke school of tea.

PHOTO: COURTESY OF ROKU KYOTO

“The postures of serving tea are clearly similar to martial arts, with fluid yet precise movements,” he says.

“The four principles of chado – wa, kei, sei and jaku (harmony, respect, purity and tranquillity) – were valid 500 years ago, are valid today, and will be valid 500 years from now. These ideals are timeless.”

He notes how the spirit of ichigo-ichie, or attitude of cherishing the present moment, is an appealing aspect of chado, which is about the shared experience between the tea master and the guests.

Where: Hogyoku-tei guesthouse in Japanese garden near Roku Kyoto 15-1a.com

Cost: Contact the Roku Kyoto concierge for pricing

Duration: Two hours

Info:

Woodblock printing (Ukiyo-e)

While Edo – as Tokyo was formerly known – is often regarded as the cradle of ukiyo-e woodblock printing, the Dotonbori entertainment district of Osaka also had a vibrant ukiyo-e history.

Dotonbori was, as early as in the 1660s, already a popular entertainment area like it is today. At the time, with Osaka being Japan’s commercial heart and the “nation’s kitchen”, the district was home to many kabuki theatres that gave rise to many famous actors.

Ukiyo-e artists used these actors as subjects for woodblock prints of their portraits in a local style that is colloquially known as kamigata-e.

The ukiyo-e woodblock printing experience at the Kamigata Ukiyo-e Museum in the Dotonbori district of Osaka.

PHOTO: YUMA HASHIMOTO FOR THE STRAITS TIMES

While the ukiyo-e of Edo is known for its elegance, that in Osaka embraces a sense of humour, bordering on caricature to show an actor’s personality.

Osaka’s ukiyo-e is said to have won over fans such as the Dutch master painter Vincent van Gogh.

Try your hand at creating a postcard-size painting by making prints from woodblocks at the Kamigata Ukiyo-e Museum under the supervision of museum director Seiko Takano.

There are three levels offered: beginner, intermediate and advanced. Although it is my first time, I take the intermediate course, printing four colours onto Japanese paper to create a picture of the Hozenji Yokocho Alley in Osaka with a girl in the foreground.

Ukiyo-e woodblock printing by this reporter.

PHOTO: YUMA HASHIMOTO FOR THE STRAITS TIMES

Interestingly, the same design is said to be able to yield different results under different hands, depending on how much paint you apply or how much force you use when you rub and press the paper against the block using a disc known as the baren.

Be sure to view the exhibits at the four-storey museum, which include ukiyo-e prints made in Osaka as well as other production tools.

Where: Kamigata Ukiyo-e Museum, 1 Chome-6-4 Nanba, Chuo-ku, Osaka, 542-0076 Japan kamigata.jp/kmgt

Cost: Museum entry at 700 yen for adults, 500 yen for high-school students and 400 yen for junior high and elementary school students. An extra fee for the ukiyo-e experience is chargeable at 600 yen for the beginner course, 1,000 yen for intermediate and 1,200 yen for advanced. Bookings are mandatory for the ukiyo-e experience and can be arranged by the Conrad Osaka concierge.

Duration: About 20 minutes

Info: