Print zines make a comeback with creative designs and niche storytelling

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

The Singapore Art Book Fair, which held its 10th edition in April 2023, has a strong following.

PHOTO: SINGAPORE ART BOOK FAIR

SINGAPORE – In an era where things do not exist until they are online, an analogue medium has been bucking the trend.

Zines, typically self-published, unserialised underground print creations, have in recent years become a preferred medium of expression and consumption for some young people.

Effectively miniature magazines, they cover topics from neighbourhood street cats to forgotten local stories, such as coconut toddy (palm wine) drinking in colonial Singapore.

But where their predecessors might have made just a few copies to distribute among family and friends, today’s zine creators hardly bat an eyelid when printing several hundred issues.

Some of these end up in London, New York and even cities in Mexico, snapped up by a niche but curious global audience interested in the relatively untold stories of a country they have never visited.

Among the most well-regarded names in the Singapore zine community now is Meantime, a history-oriented zine created by Mr Pang Xueqiang, 31, and his course mates from Nanyang Technological University’s (NTU) Wee Kim Wee School of Communication and Information in 2019.

On issue four this year, the annually published zine is best known for its “shape-shifting”. The latest issue ($37), inspired by the seven deadly sins, sliced off the entire bottom right corner of the zine so that it seems to tilt precariously when placed on a surface.

When opened, it makes for an unconventional reading experience, an inventive gimmick to attract new readers.

“It’s baffling, to be honest,” Mr Pang says of Meantime’s popularity beyond Singapore’s shores. “We don’t overexplain. We get e-mail saying that the shape appeals to them, that it’s a rare Singapore publication and that it’s a very nice way to explore a country.”

Meantime zine’s fourth issue, inspired by the seven deadly sins, sliced off the entire bottom-right corner so that it seems to tilt precariously when placed on a surface.

PHOTO: MEANTIME

A review in British magazine reviewer and purveyor Stack in April put it on the map, and Meantime now sells 800 copies an issue, about half of which are distributed overseas.

Previously an aspiring journalist, Mr Pang now helms the zine full-time. He supplements his income with part-time jobs such as teaching and freelance copy-editing, but most of his time goes to finding stories that can give Singapore’s perceived “dry and boring” history a fresh spin.

For one story, Meantime found six young men with long hair and got them to have conversations with their fathers who lived through Operation Snip Snip, an anti-long-hair campaign launched by the Government in the late 1960s and 1970s to curb the influence of hippy culture.

“When we started, we had zero knowledge about distribution and publishing,” Mr Pang says. “Now, we are stocked at Books Kinokuniya, Basheer Graphic Books and Objectifs. Singapore is small, so a lot of stories have been repeated. It’s about finding something new to say again.”

Meantime’s third issue featured a “chewed-up” cover and was themed Funny Stories.

PHOTO: MEANTIME

Historically, zines have been associated with this impulse to say something new, but more important was its association with the voices of the marginalised.

Most place its modern beginnings – ignoring those who say zines began in the 1500s with Martin Luther’s 95 Theses – in 1930s United States, which is today still very much the centre of zine culture.

Though at first especially popular among science-fiction fans, zines were taken over quickly by punk culture in the 1970s.

In Singapore, BigO magazine, which focused on music news and reviews, is an acknowledged pioneer. Its earliest issues in the 1980s were photocopied, part of a cut-and-paste culture in a pre-Internet era when information, especially that related to the counterculture, was hard to come by.

Today, most zines are less “political” and span a greater gamut of more innocuous topics. There is even an annual event at the Singapore Art Museum (SAM) – the Singapore Art Book Fair, run independently by founder and director Renee Ting, 31.

Its recent 10th edition, held from April 14 to 16, attracted more than 100 local and international art book and zine exhibitors, including vendors from Argentina, Australia, France, India, Hong Kong, Japan and Indonesia.

The fair draws long queues. In 2022, when entry was free, 6,000 people thronged the venue. The $8 admission fee introduced in 2023 put some folk off, but 4,000 paid to enter.

Ms Ting says about the ticketing decision: “It was important for me that an event that is independent and somewhat large-scale can be sustainable. I didn’t think it was fair to charge exhibitors more.”

The queue at 2023’s Singapore Art Book Fair, where 4,000 people paid an admission fee of $8.

PHOTO: SINGAPORE ART BOOK FAIR

She notes that the scene has evolved in the past decade. “When the festival started in 2013, the community here was very skint, with very little content. The idea of being self-published was still quite unfamiliar, at least to me.”

In 2017, she quit her job at Books Actually to organise the Singapore Art Book Fair full-time, changing it from a by-invite-only event to an open call for vendors, with a greater focus on international participants.

South-east Asia’s first art book and zine festival then began to gain more attention – itself a driver inspiring more creators to see zines as a viable mode of self-expression.

Zine-making is now almost a rite of passage for many young creatives.

Shrub at Golden Mile Tower is another retail hub for zines and a meeting point for like-minded artists, together with design book stalwart Basheer Graphic Books at Bras Basah Complex.

Established artists, such as photographer Robert Zhao, also started with zines.

Why zines?

The zine resurgence is ironically driven by the widespread digitisation of the 21st century. Zine-makers say more people are making and buying zines precisely because many now value holding something tangible.

The phrase “time capsule” comes up multiple times in interviews.

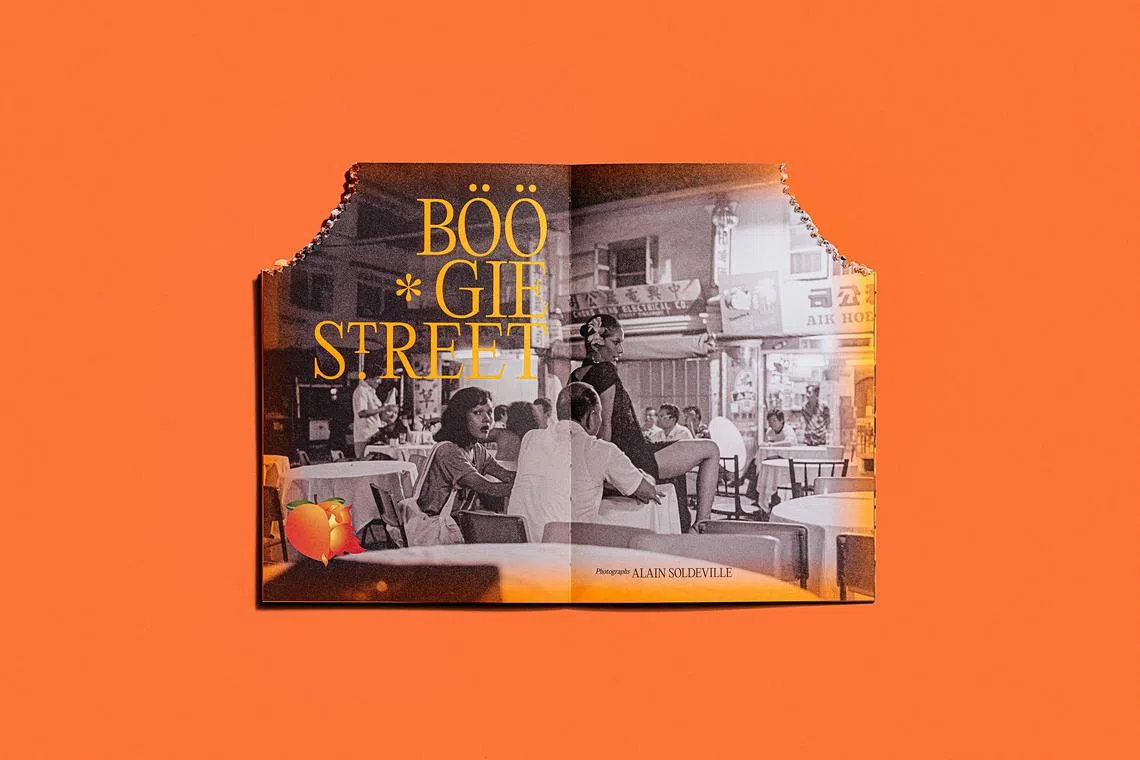

As Mr Chen Yi An, 25, of arts and design zine Now & Again ($24), says: “It is a time capsule of that period in time of what creatives are interested in. In print form, people can also flip through it to find things to inspire their own projects.”

Now & Again, an arts and design zine.

PHOTO: NOW & AGAIN

Each zine almost instantly becomes a vintage relic once made and purchased in this rapid digital culture.

Ms Christy Chua, 24, founder of food zine The Slow Press ($24), compares the surge in interest in the medium with the popularity of vinyls.

“You can touch and feel it, put it in your house to look at. There is a certain memory attached to that. A digital version disappears and has a much lesser impact.”

The team behind food zine The Slow Press: (from left) art director Melody Koh, editor Laetitia Keok, founder and editorial director Christy Chua, and editor-in-chief Tan Aik.

PHOTO: YVONNE LEE

But like the zines of old, a more potent draw is the medium’s versatility and low barrier to entry. Zines can be anything that creators want them to be – comprising entirely illustrations or with no attention paid to the quality of the paper and design, with no obligations for a next issue.

They are exempt from the dictates of market appeal or the “mature” decisions of an older editor. Mr Chen, who once interned at a fashion magazine and found it stale, says zines are not beholden to the “capitalistic lens”.

“The focus is on the creative content,” he says. “When we started, people kept asking, ‘Who is this for? Who will buy this?’ We didn’t know, but we really just wanted to make something.”

Many zines have also taken it upon themselves to centre on stories or niche interests neglected by mainstream media, continuing, in less controversial ways, the rebellion of zines past.

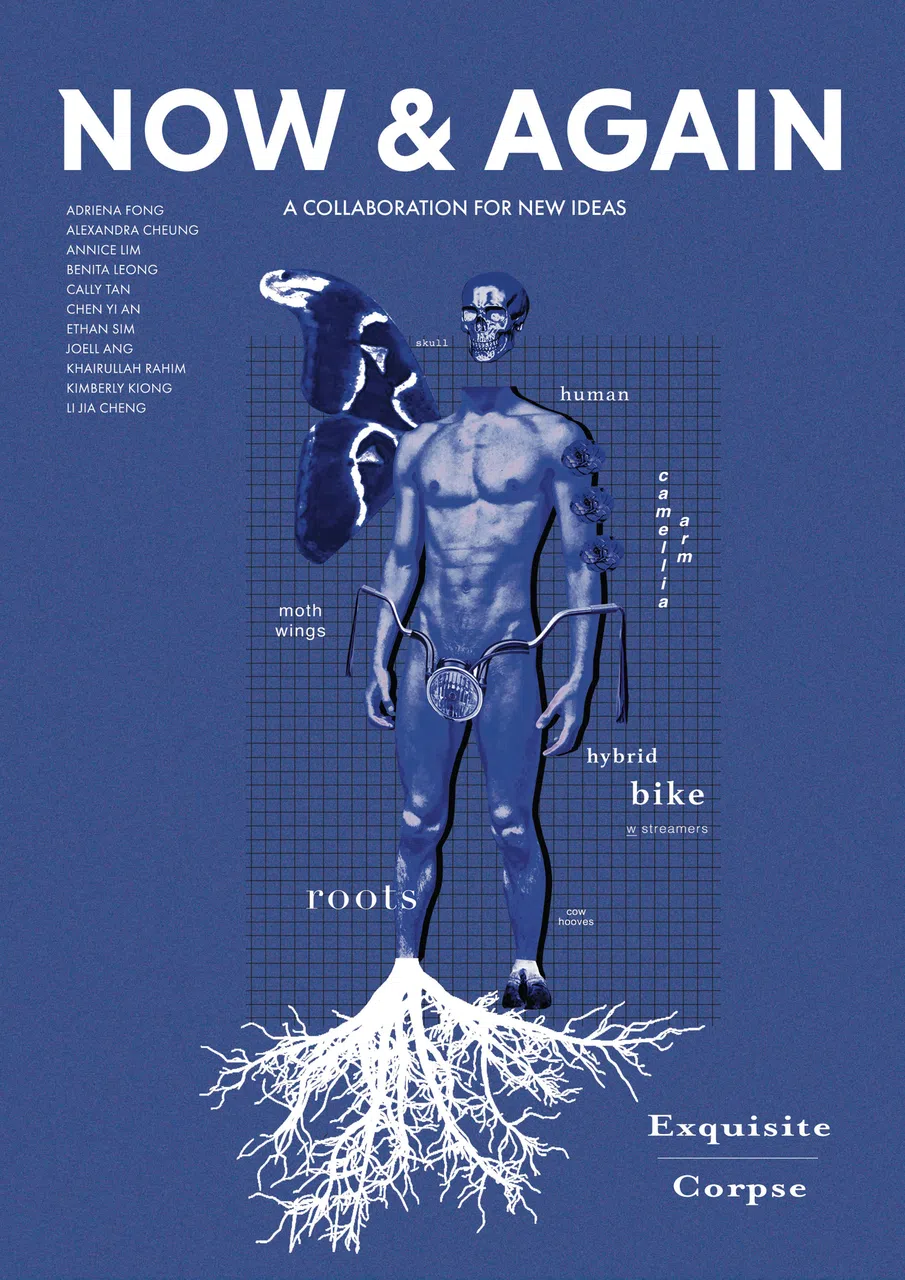

The Slow Press recently put out a special edition called By The Moon And The Tides ($28), focusing on prominent foragers in Singapore.

Featuring interviews with self-taught forager Esmonde Luo, Syazwan Majid of Wan’s Ubin Journal and Firdaus Sani of Orang Laut Singapore, the spiral-bound zine spotlights the practice of picking food directly from the natural environment.

Ms Chua says: “We don’t need business opportunities or advertisements, so we can feature more in-between stories. There’re a lot of good reviews and a lot of recipe books, but not enough focus on local businesses and the people who are exploring their own craft or food. This is just a very organic way of exploring how we can appreciate food better.”

The Slow Press recently put out a special edition called By The Moon And The Tides, focusing on prominent foragers in Singapore.

PHOTO: THE SLOW PRESS

Definitions

But a look at zines such as Meantime, Now & Again and The Slow Press has left some scratching their heads.

Their high production quality and well-researched pieces make it hard to distinguish between them and full-fledged magazine operations.

Their price points are also above $20, with print runs of several hundred issues that are stocked in bookstores instead of mailed directly to subscribers.

There is the valid question raised by some in the community, of whether the zines have deviated from and lost some of the guerilla, handmade quality that makes them what they are.

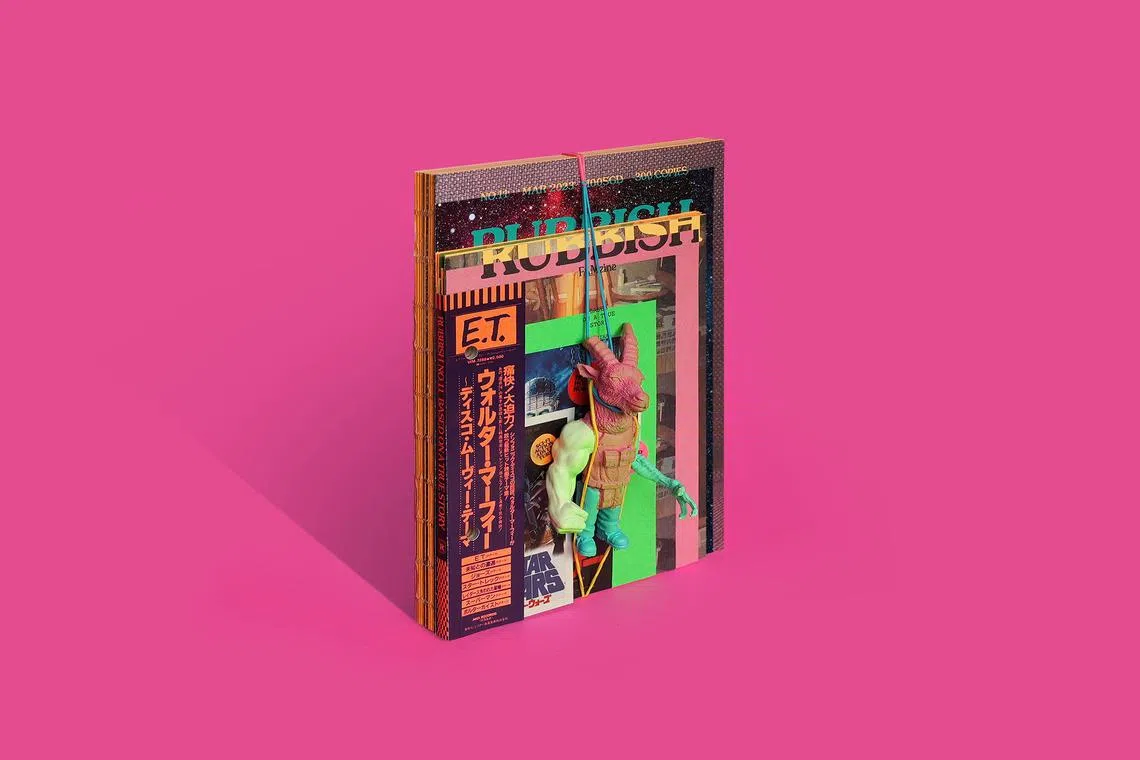

Rubbish Famzine, one of the most established zines here, has come under similar criticism.

Started by Mr Pann Lim, 50, creative director of design and advertising studio Kinetic Singapore, the zine began in 2013 as a family project with his wife and two children, now aged 20 and 17.

(From left) Mr Pann Lim, his children Aira and Renn, and his wife Claire started Rubbish Famzine in 2013 as a family project.

PHOTO: RUBBISH FAMZINE

There is a conscious tatty and faded zine aesthetic to Rubbish Famzine, which comes wrapped with small items, such as reproductions of memorabilia brought back by the Lim family from a holiday in Tokyo and Kyoto. But each issue can cost upwards of $80, a massive premium compared with early zines, which were mostly free or sold for a nominal fee.

When asked about such complaints, Mr Lim had no comment on the matter. He says, however, that the money they make goes into producing the next issue of the annual zine.

He likens the process of creation to that of a chef in a restaurant: “You cook for yourself first.” In this spirit, one of Rubbish Famzine’s issues was dedicated to Mr Lim’s late father.

“We wanted to create an archive of family memories with our kids since they might not care as much about their family when they are teenagers,” he says.

“For me, this is for ourselves and the full impact will happen only when (my children) are in their 30s, when they look back on the older issues and remember.”

Rubbish Famzine, which has a conscious tatty and faded zine aesthetic.

PHOTO: RUBBISH FAMZINE

Multidisciplinary zine collective Creatures Of Habit – comprising 22-year-old students Yu Ke Dong, Bryan Ge and Lim Yi Tian – says the increase in quality and types of zines all add to the breadth of the market, from homemade scrapbooks to elaborate works of art.

Their zine started in 2017 as one focusing on broad social themes such as urban alienation and public spaces, but, in a natural evolution not unusual for the scene, has since become a platform for their individual one-off zines, from a photo book of moss to a collection of haunted spaces.

They say: “There’s something for everyone. Some people enjoy how down-to-earth and relatable zines can be, while others prefer zines that appeal to their niche interests. Most times, it’s just the joy of owning or making a piece of creative work that may not be found in the mainstream market.”

Ms Ting is addressing this divergence with Cut Copy Paste, a zine festival at Temasek Polytechnic in January that disqualifies any zine which costs more than $25.

“There are people trying to bring it back down, making it more accessible and inexpensive, and hopefully, we move towards that,” she says.

But she is confident that zines, in whatever form, will endure.

She adds: “The very fact that it is self-published means there are no gatekeepers and you are essentially free to represent your ideas however you want in print.

“During the Hong Kong protests,