Book review: Yu Miri’s The End Of August a feat of multilingual translation set in colonial Korea

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

This behemoth of a book by Yu Miri is no light read and will reward only the scrupulously patient reader.

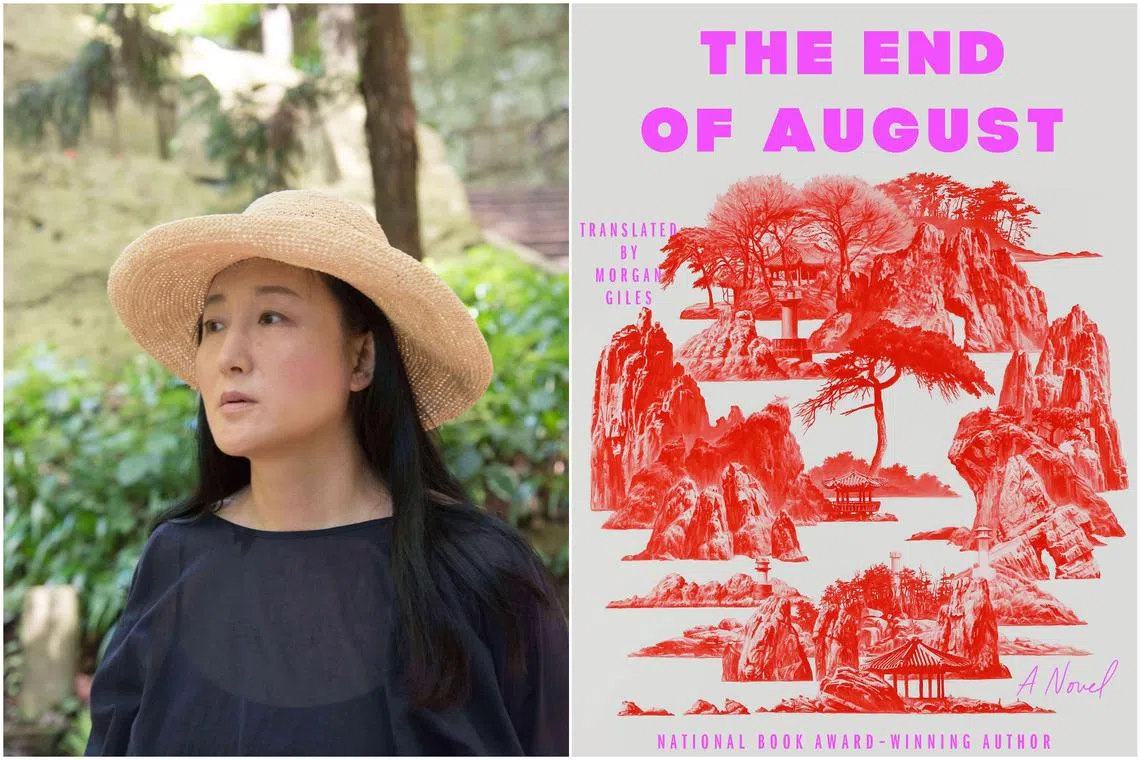

PHOTOS: RIVERHEAD BOOKS

Follow topic:

The End Of August

By Yu Miri, translated by Morgan Giles

Fiction/Riverhead Books/Paperback/710 pages/$33/Amazon SG ( amzn.to/48fWEjk

4 stars

Spanning Korea’s tumultuous 20th century and told in at least four languages through the perspectives of more than 30 characters, Yu Miri’s The End Of August is pure literary ambition.

This behemoth of a book by the Japanese-language writer of Korean descent is no light read and will reward only the scrupulously patient reader. It demands a tolerance for shifting viewpoints, unconventional punctuation and a generous appetite for acclimating – even surrendering – to the denseness of a multicultural colonial world.

Partly autobiographical, the novel sees a fictional Yu Miri revisit her grandfather Lee Woo-cheol’s life in Japanese-occupied Korea as a running prodigy hoping to compete in the 1940 Tokyo Olympics.

Among his influences are Woo-hong, his friend who joins the revolutionary Heroic Corps, and his rival athlete Sohn Kee-chung – a Korean who won gold, albeit under Japan’s flag, in the 1936 Berlin Olympics.

Throughout the intriguing, if excessively wordy, novel, there are stories of comfort women, ghosts, mistresses, labourers and revolutionaries that percolate in the town of Miryang, one of the key sites for the Korean independence movement.

The book’s blurb calls The End Of August a “marathon of literature”, but it is equally a marathon of translation for London-based translator Morgan Giles, who also translated Yu’s National Book Award-winning Tokyo Ueno Station (2019) – which deals much more succinctly with the 1964 Tokyo Olympics from the perspective of a migrant labourer.

Giles brings an impossibly meticulous and masterful hand in rendering the multilingual novel in its kaleidoscopic breadth.

She translates from a novel written primarily in Japanese, but its Korean characters whisper a clandestine Korean language that must not be heard by their occupiers.

To conjure this intimate linguistic underground of gossiping bathers and rebellious students, Giles leaves much of the Korean untranslated – with words like ilbon saram (Japanese people) and wae-nom (a Korean slur against Japanese people) only gradually accumulating meaning.

The linguistic acrobatics is part of the novel’s difficulty as well, and it is only well after the first 100 pages that the reader finally finds a footing in the narrative.

The novel, despite several draggy chapters, renders multilingual life in the way the best multicultural epic novels do. One immediately thinks of Indian writer Amitav Ghosh’s Ibis Trilogy (2008 to 2015) or Darryl Sterk’s translation of Taiwanese writer Wu Ming-yi’s The Stolen Bicycle (2017).

Perhaps most unthinkable to the English-language reader today is the fact that the novel was first published as serialised chapters simultaneously in the Japanese newspaper Asahi Shimbun and South Korea’s Dong-A Ilbo in the early 2000s.

It is, therefore, a book tied intimately to two reading publics which attempts to speak across varying – even opposing – historical consciousness.

Such is the book’s improbability in its original languages, and The End Of August is Giles’ gift to English-language readers, who can now witness and labour through this difficult history.

If you like this, read: Pachinko by Min Jin Lee (Grand Central Publishing, 2017, $32.35, Amazon SG, go to amzn.to/47pXOro

This article contains affiliate links. If you buy through these links, we may earn a small commission.