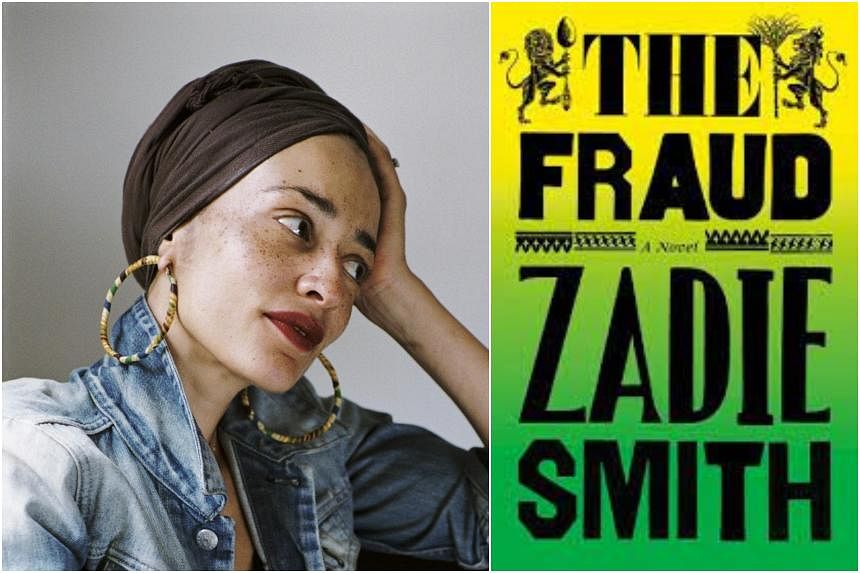

The Fraud

By Zadie Smith

Fiction/Hamish Hamilton/Paperback/454 pages/$34.86/ Amazon SG (amzn.to/3HacKio)

4 stars

In this first historical novel by literary superstar Zadie Smith, the titular fraud is many things.

It is an insecure writer paralysed by his own capricious fame and a bumpkin claiming to be the rightful inheritor of a baronetcy. It is also a black man living in material comfort as his peers toil away in plantations far afield.

Even Elizabeth Touchet, the reader’s indignant, widowed guide to Victorian England, is not spared from the charge. Claiming to know poverty, she is brought down an alley to a “dolly shop”, and finds herself baulking at the interior piled high with parts of things rather than things themselves: chair legs, heads of hammers, shoes without soles.

This is a different kind of historical novel by Smith, one less streamlined and propulsive, but at once more diffuse and expansive in its recreation of an important English century.

Victorian England was when Pax Britannica was the order of the day, but it was also a time of immense social and moral upheaval, a polity reeling from the Chartist movement, franchise reform and the official abolition of slavery.

The Fraud, incorporating contemporary debates, is ostensibly about the Tichborne trial, a judicial cause celebre from 1873 to 1874 where an obvious impostor to an aristocratic estate received unexpected mass support from Britain’s working classes.

Rather than tense court drama, it more resembles Mrs Dalloway’s stroll in Virginia Woolf’s novel.

Finding herself inexplicably drawn to the London trial, Touchet, a cousin by marriage to novelist William Ainsworth and also his housekeeper, wanders the city, remarking on the railway tracks replacing rivers and the construction of slipshod graves in Surrey during a cholera contagion.

More engrossing are the peregrinations of her mind, as Smith splices in an assortment of Touchet’s memories.

Touchet thinks back to when she was momentarily drawn into a push-pull romance with separately Ainsworth and his wife, a threesome that might have sufficed for a whole novel, but one that Smith almost insouciantly refuses to make the focus her story.

Instead, she goes for breadth, infiltrating also the erudite literary circles of 1800s England and its attendant salon culture.

Appropriating the affected highfalutin language of the literary cabal at Ainsworth’s house parties – a real-life group that included Charles Dickens, caricaturist George Cruickshank and painter Daniel Maclise – she conjures in its full ruckus these self-important men pontificating about current events, who mockingly liken their labour to slavery, while barely acknowledging Touchet’s presence except to demand more port.

The trial becomes catalyst for a belated coming-of-age for Touchet, now suddenly interested in writing but also newly aware of the uncontainability of the world by words.

Sincerely moral and yet, like many of her time, hopelessly blinkered, her position of both privilege and servility make for an attractive, sardonic character.

Unable to travel because of her sex, she suspects that “England was an elaborate alibi”, untouched by revolution unlike its European counterparts and where only dinner parties and boarding schools and bankruptcies occurred.

At the height of empire this had further resonance: “Everything else, everything the English really did and really wanted, everything they desired and took and used and discarded – all of that they did elsewhere”, not least Ainsworth with his continental affairs.

About two-thirds through the novel, Smith has to deal with the elephant in the room – slavery. She makes an audacious perspective switch, jerking readers to the slave plantations of Jamaica, where Bogle, now key witness in the Tichborne trial, was born.

Unlike the delicate pointillism of Touchet, Bogle’s story is constructed with much broader strokes, Smith racing from Bogle’s father’s abduction from Africa to Bogle’s own dishonourable exile to Australia.

His interior life is neither as rich or interesting, and though at parts poignant is still stereotypical. There is a sense of punches pulled, an unwillingness to speculate or ambiguate his conduct on Smith’s part that is a letdown after her irreverence with other characters.

But Smith’s writing is ever so elegant, the sparseness perfectly measured and its own propulsive force, the short two- to three-page chapters light enough as vignettes to keep the pages turning.

The Fraud’s multifacetedness may lack the sharpness of Smith’s more contemporary works, but its relentless skewering of all manner of privilege is subtle enough to draw parallels while differentiating between the axes of injustice.

It may finally be the less powerful but more ethical way of reclaiming the period and its chorus of voices.

If you like this, read: Horse by Geraldine Brooks (Abacus, 2022, $30.44, Amazon SG, go to amzn.to/3twRVuJ). A record-breaking thoroughbred ties the story of an enslaved groom in 1850 Kentucky with Theo, a Nigerian-American art historian in 2019 Washington, DC.