Book review: Sarah Bernstein’s Study For Obedience technically polished, but fails to engage

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

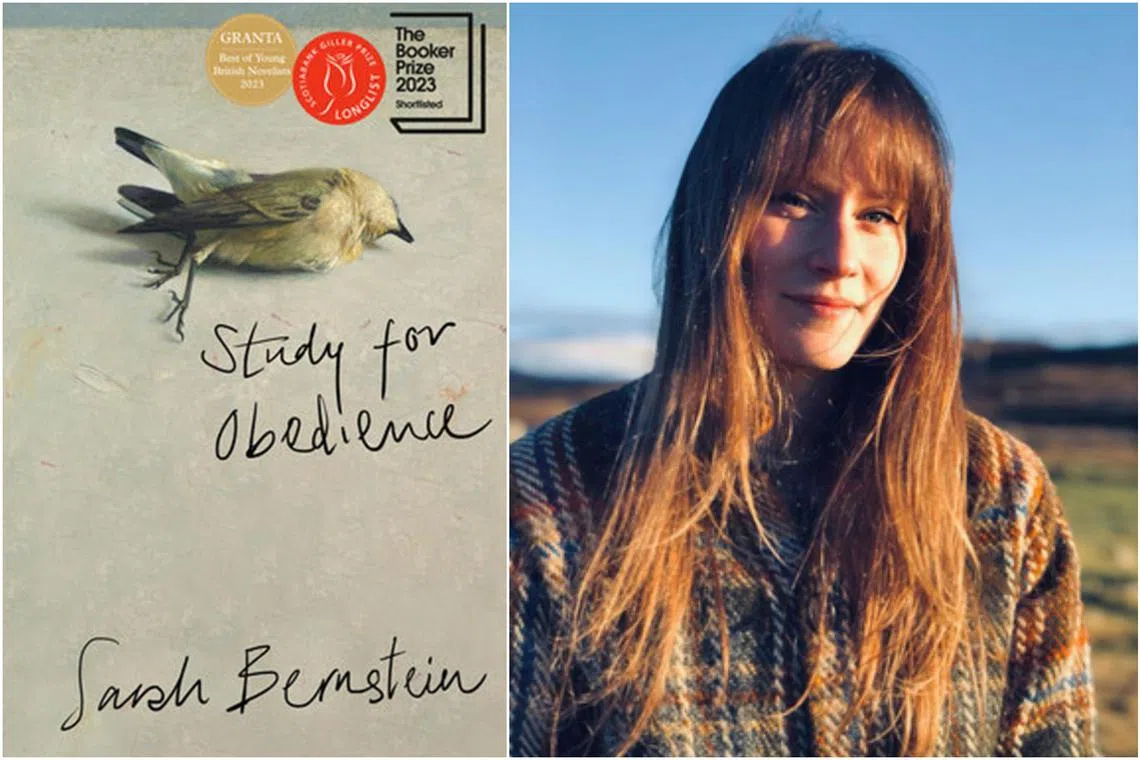

Canada-born, Scotland-based Sarah Bernstein's sophomore book Study For Obedience has been shortlisted for this year's Booker Prize.

PHOTOS: GRANTA, ROBIN IRVINE

Study For Obedience

By Sarah Bernstein

Fiction/Granta/Hardcover/193 pages/$35.41/Amazon SG ( amzn.to/3LuB8hv

3 stars

Do not let the compact size of this book fool you. Short as it is, it is a technically challenging read that demands its reader’s full and careful attention.

Whether you find it a rewarding read, however, depends on your tolerance for experimentation and a narrative that strives for nuance and ambiguity so strenuously that it collapses into amorphous abstraction.

An unnamed woman arrives at a rural residence, vaguely situated to the north of somewhere, to live with her brother whose marriage has fallen apart.

She is ostensibly keeping house for him, but the tasks and responsibilities she undertakes seem closer to slavery than mere housekeeping.

At the beginning, she seems to settle easily into the routine of working remotely – transcribing notes for a law firm while ambling through the rural countryside and winding up courage to visit the nearby village where a different language is spoken.

Things get weirder as the aimless narrative throws in random events.

The village’s cows suffer from hysteria and have to be put down. A neighbour’s dog develops a phantom pregnancy. The protagonist stumbles upon an ewe with a lamb dead from overlong labour, still hanging from its rear.

There is also an inexplicable antagonism between the narrator and the villagers – something the narrator attributes to her unfortunately timed arrival in the midst of these small natural disasters and the villagers’ superstitious bent.

But despite her protestations of innocence, she also develops a habit of weaving figures out of reeds and leaving them on doorsteps – a gesture that could be read as threatening.

The first-person narrative is singularly devoid of personality, except for such constant self-deprecation that it descends into grovelling self-effacement.

The protagonist describes herself as moving through life with “a surface placidity”, “plodding, plodding, where certain teachers had in my youth described as a kind of idiot impenetrability”.

The description could equally be applied to this narrative, where multiple “Big Themes” – of gender/race/class discrimination, of morality and responsibility, of intergenerational trauma, of language and its slippages – are alluded to, but never quite explicated or engaged.

It is easy to see why this book is Booker bait. Canada-born, Scotland-based Sarah Bernstein writes with the kind of cerebral carefulness that one would expect of someone who teaches literature and creative writing, parsing sentences and clauses, punctuation and construction with the ascetic rigour of an academic.

She finds nuance in the lack of commas in a sentence: “I had always loved the countryside, the north, trees in snow, but I had to tell the truth not expected to find quite so much violent death.”

There is menace in her poetic concision: “A hanging, tremulous, a doorway and a tidy garden.”

The metatextual references guarantee this work a well-earned place in post-modern literature reading lists in universities.

For all its technical accomplishments, however, Study For Obedience never quite draws blood.

Its deliberate geographical vagueness is perhaps aimed at emphasising the universality of its themes of racism and hatred. Certainly, the unformed nature of its setting pushes the reader to see this as a fable.

Yet, there are distractingly concrete details that yank the reader back towards realism, such as an extended description of the narrator’s mother in the kitchen, “stuffing the kishke, salting the liver, breading the chicken, chopping the herring”, which immediately suggests eastern European Jewish ancestry.

This one crumb of a reference is dropped, but the trail leads nowhere as the narrator retreats once again into vague generalisations.

The trope of the unreliable narrator is a common one in modern fiction, from F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby to its most magnificent exemplar, Ford Madox Ford’s The Good Soldier. Those works offered enough narrative ballast to engage the reader deeply in the characters and themes.

The onus in Bernstein’s book, however, is laid entirely on the reader to draw from the patchily non-linear narrative whatever scraps of themes and meaning they wish. In the end, its wispy equivocations and pale suggestiveness fail to satisfy.

If you like this, read: Mrs Dalloway by Virginia Woolf (Penguin Classics, 2021, $23.13, Amazon SG, go to amzn.to/3EVD1QF

This article contains affiliate links. If you buy through these links, we may earn a small commission.