South Korean women get short hair to push back against anti-feminists, some get called ‘gross’

Sign up now: Get insights on Asia's fast-moving developments

Ms Kim Ah-yeon (left) and Ms Han Ji-young are some of the participants of a campaign that encourages women to show off their short crops.

PHOTOS: COURTESY OF KIM AH-YEON, COURTESY OF HAN JI-YOUNG

Follow topic:

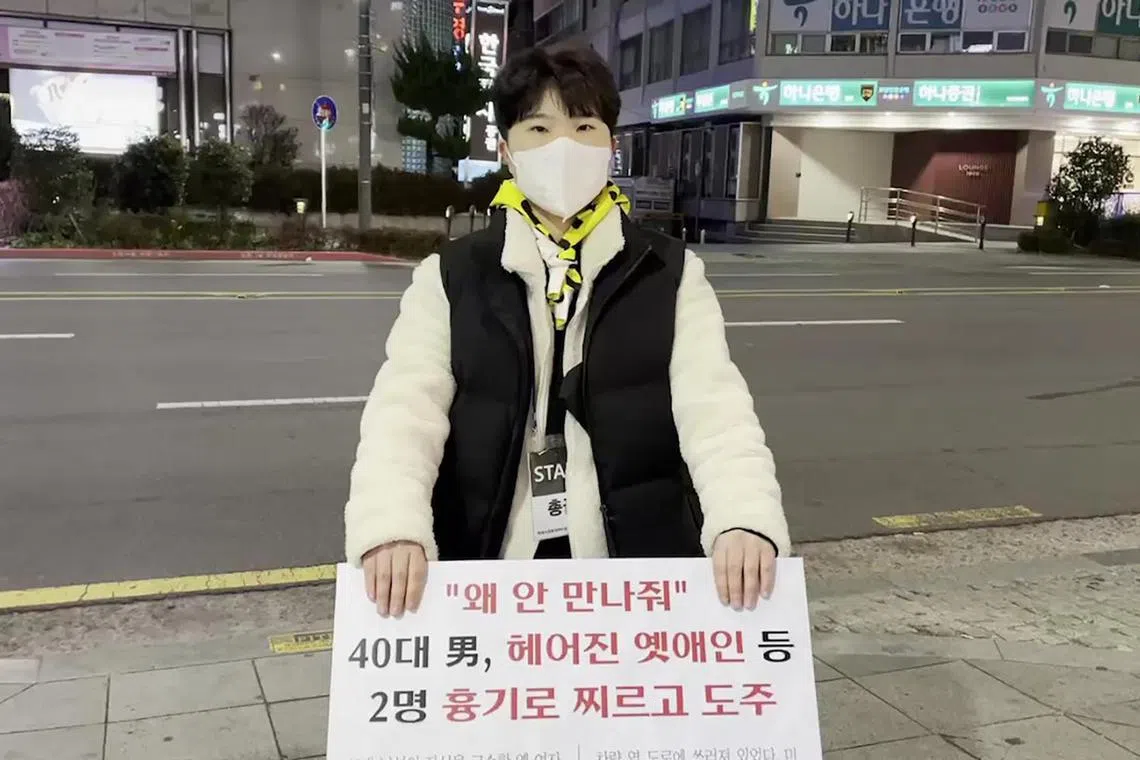

SEOUL - It has been three years since office worker Kim Ah-yeon chopped her long locks off and got a boy’s haircut. And till today, she still gets asked why she keeps her hair so short and why she chooses to be so “unfeminine”.

Walking on the streets, she sometimes gets hurled insults like “You look disgusting!” and “Why do you look like a man?”, and even gets called a witch.

In the office, she notices that some male colleagues will shun her and deliberately ignore her when she greets them in the morning.

“I feel pressured by my family and society every single day. My short hair does not cause hurt to other people, yet they call me gross and tell me to be more feminine,” she told The Straits Times.

Ms Kim Ah-yeon, 28, is one of the growing hundreds of participants of an online campaign that encourages Korean women to show off their short crops with the hashtag #women_shortcut_campaign.

The campaign was triggered by a Nov 4 attack on a short-haired female convenience store clerk

The attacker was a man in his 20s, who accused the victim of being a feminist since she has short hair.

“I don’t beat women, but feminists are asking to be beaten up!” he allegedly told her, before punching and kicking her.

The attacker, who was arrested on the spot, was said to be drunk and told police that he was affiliated with New Man on Solidarity, one of the country’s most active anti-feminist groups.

The group denied that the attacker is affiliated with it and stated on its online community page that its members do not assault people.

An anti-feminist movement has been growing in the patriarchal country since the 2022 election of President Yoon Suk-yeol, who openly wooed young men who felt they were losing out as women became a bigger voice in society.

South Korea’s feminist movement has picked up pace since the #MeToo movement against sexual harassment in 2018.

This led to the Cut the Corset movement in 2019, which saw many young women breaking free of conventional beauty ideals and choosing to go make-up free and bra-less and cutting their hair short.

Office worker Kim Ah-yeon heads an online feminist community called Blazing Fire.

PHOTO: COURTESY OF KIM AH-YEON

Backlash from men came in the form of street rallies to denounce feminists as man-haters, and a social evil that needs to be eradicated. Feminist leaders were mocked in YouTube videos, and their personal details exposed online.

The latest assault, on Nov 4, has outraged many women’s groups.

Ms Kim Ah-yeon, who heads an online feminist community called Blazing Fire, said: “Would a man be hit for short hair? The fact that a woman was assaulted for having short hair is clearly a misogynistic crime. I am now scared that I may be assaulted for the same reason.”

To Dr Lim Myung-ho, a professor of psychology at Dankook University, the attack is a sign that “the anger against women that has been suppressed, is now being expressed.”

“We should look into this incident and consider to what extent gender-based discrimination is normalised in society,” he told The Donga Ilbo newspaper.

Gender equality is a touchy issue in Confucian Korea, where patriarchal ideologies and practices remain deeply entrenched.

Despite its successes in the modern world with leading technology companies and soft-power cultural exports, South Korea has the largest gender pay gap among the 38 members of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

Where on average, women in OECD countries earn 11.9 per cent less than men, the gender gap is 31.1 per cent in South Korea.

In terms of gender equality, South Korea fell five places from 99th to rank 104th among 146 countries in the Global Gender Gap Report 2023, issued by the World Economic Forum.

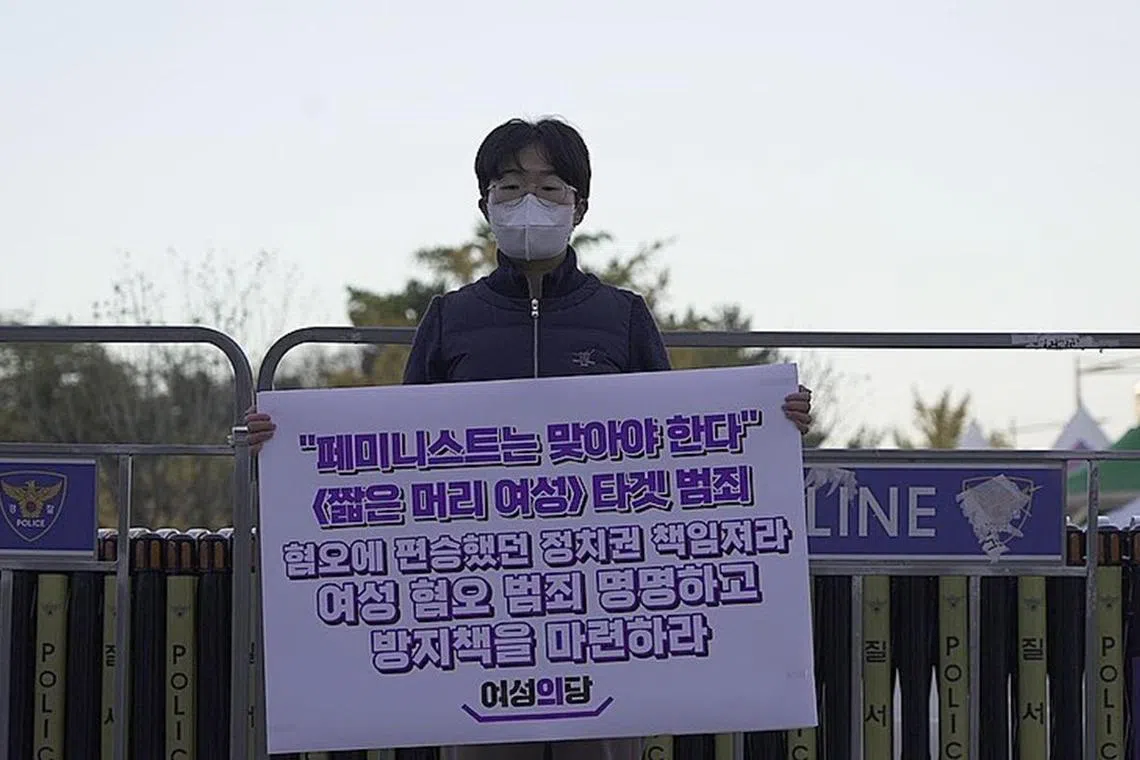

Ms Kim Ju-hee of feminist group Team Haeil did a one-person protest at the National Assembly on Nov 7 after the attack on a convenience store clerk.

PHOTO: COURTESY OF KIM JU-HEE

The index ranks countries based on economic participation and opportunity; educational attainment; health and survival; and political empowerment. For context, Iceland ranks tops, while Afghanistan takes the bottom spot. Singapore is ranked 49.

Ms Han Ji-young has sported short hair since the Cut the Corset movement and was the originator of the hashtag #women_shortcut_campaign in 2021.

The physiology psychologist, who teaches healing through body movements, created it after being disturbed by the fact that national archer An San’s three-gold-medal haul at the Tokyo Olympics was eclipsed by the fact that she had short hair.

Anti-feminists had launched online attacks at An San, calling her a radical feminist because of her hair.

Ms Han, 47, said she was aghast at the audacity of the Jinju assault and is calling for other women to stand in solidarity against such attacks.

“Korean men who use these ridiculous reasons as an excuse to threaten women’s bodies and rights must be sternly punished, adequately educated, and warned,” she said.

She feels that the vitriol against women in some of the online male communities has grown greater than before and is hoping that the campaign – which gained global traction in 2021, spawning close to 7,000 posts – can revive awareness of gender equality issues in her country.

But just as feminism grows in the country, anti-feminist groups like New Man on Solidarity and Dangdangwe are pushing back.

Complaints include assertions that men are disadvantaged in the job market because of mandatory military service. Moreover, because most women stop working after marriage and childbirth, the burden of taking care of household expenses still falls on men.

As the young generation in South Korea struggles with unemployment in a hyper-competitive job market and also skyrocketing housing prices, the resentment grows, says Assistant Professor Kim Jin-sook from Emory University, who studies online misogyny and feminism.

“The problem is that the frustration and resentment of young Korean men become sources of hatred against women and other minority groups.

“They often ascribe their sense of incompetence and victimhood not to the capitalist system or neoliberal policies, but to women whom they see as preventing them from receiving their due.”

Prof Kim also believes that the rise of anti-feminist sentiment was fuelled mainly by President Yoon’s 2022 political campaign, which capitalised on the negative emotion.

It included a pledge to shut down the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family, which ensures that government policies do not discriminate based on gender.

By trying to woo the disgruntled young men who see themselves as being treated unfairly in various socio-economic contexts, the politicians have ignored “the systematic inequality or discrimination present in Korean society,” said Prof Kim.

While President Yoon has yet to follow through on abolishing the gender ministry, the agency’s 2024 budget has been cut from 710 million won (S$740,000) to 410 million won.

In what critics see as a backslide, the ministry will also be removing grants for projects aimed at expanding gender equality and women’s social participation.

Upset over the Jinju assault and the budget cuts, feminist group Team Haeil’s leader Kim Ju-hee staged a one-person protest outside the National Assembly on Nov 7.

She told ST: “How can they say there is no structural gender discrimination? Gender discrimination is getting worse and women’s lives are getting more painful.”

She feels that the politicians are equally culpable for the Jinju attack.

“This case isn’t just about the attacker. Politicians who actively supported and advocated anti-feminism are equally responsible for this much misogyny in Korea,” she said.

She wants recognition that there is a divide.

“For women to have more equal rights, we need to acknowledge that society is currently sexist, and recognise that ensuring more opportunities for women is simply levelling the field and not female superiority. We need to recognise that the world we live in is a tilted playground to move on to the next stage.”

But even small steps take time. During the protest, a man came over to pick a fight with her, but the police intervened.

Since joining the feminist movement in 2019, Ms Kim Ju-hee, 28, said she has been the target of similar attacks, mostly online mockery, stalking and threats.

“I have been through hell and back, and yet people ask if such persecution really exists. It does but when I tell people, they would say, ‘Then don’t be a feminist’, or ‘Start growing your hair’.”

But she is adamant that she will never go back to growing her hair long again.

“Just because a woman has short hair doesn’t make it a reason for us to suffer assault. We will keep our hair short as a protest against the patriarchy.”