BEIJING – Tens of thousands of PCR testing booths are littered across China, with many residents just a 15-minute walk away from a swabbing point.

Now that Covid-zero has abruptly ended, cities are left with the problem of what to do with them.

Some have been retracted by operators, consigned to the scrap heap or listed on second-hand online marketplaces for resale. Others have become eyesores, abandoned on the streets, battered by the elements.

But some local governments and communities are coming together to creatively reconfigure these unwanted relics into new landmarks.

As infections surged in December after China’s Covid-zero U-turn, cities from Shenzhen to Changsha transformed polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing booths into fever clinics and medicine distribution sites to reduce pressure on overwhelmed hospitals.

At these booths, sick residents could get a diagnosis and use their state medical insurance to buy drugs near their apartments.

The testing build-out cost around 200 billion yuan (S$39 billion) to set up – about equal to the gross domestic product of Estonia, according to calculations from Goldman Sachs.

The immense expense of Covid-zero controls, alongside a slowing economy, has led to a ballooning debt burden for municipalities. Repurposing that infrastructure could help them recoup at least some of the costs.

Suzhou, a city 100km west of Shanghai, has gone further to reanimate these booths than anywhere else. The local government offered around 30 empty kiosks for free to entrepreneurs to convert into food and souvenir stalls as part of a Chinese New Year market, selling speciality produce and local snacks.

The booths will continue to be available for merchant use to bolster consumption and tourism efforts, the district’s officials told Chinese media.

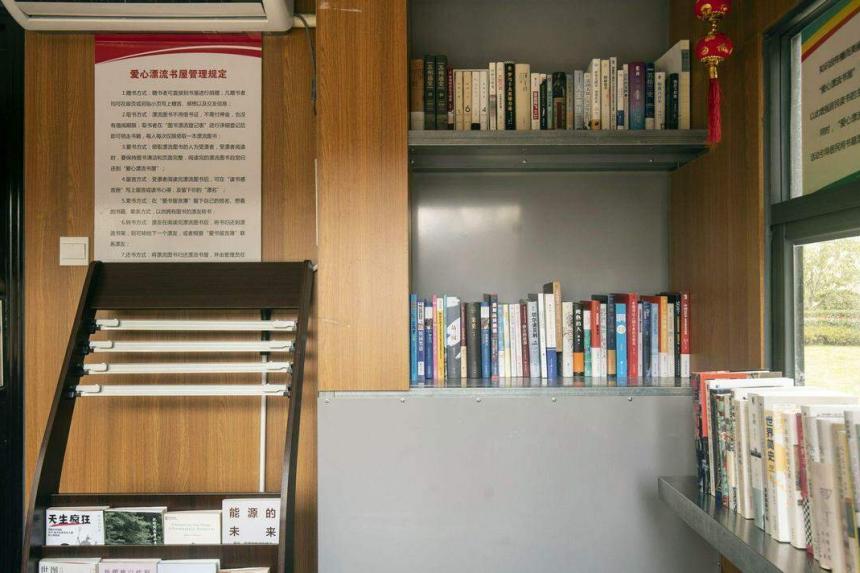

Elsewhere in Suzhou, booths have been transformed into libraries for residents to read and donate books. Others have become rest stations for sanitation workers and cleaners, offering microwave ovens and hot water.

A few have even become mini fire stations stored with safety equipment. Outside the city’s rail station, officials from the Human Resources and Social Security Bureau have converted a row of testing booths into employment help centres for migrant workers.

The change is dramatic, considering that as recent as early December residents still lined up in the hundreds to have their throats swabbed by so-called “big whites”, the ubiquitous white-clad enforcers of Covid-19 rules.

Green QR codes reflecting negative results within 48 hours were needed to get around most places. Positive tests usually meant the person would be dragged off to a quarantine facility.

“I’ve seen some of the empty booths idling around. It brings back bad memories,” said Ms Janice Qu, a housewife in her 40s in Shanghai. “I like the idea of giving them a makeover. There could be some nice business opportunities.”

China isn’t the only country that has seen its cities and streetscapes transformed by Covid-19, but the sheer scale and duration of the community disruption there is virtually unparalleled.

During the Covid-zero years, spread of the virus was minimal but the social and economic disruption from lockdowns cost livelihoods and lives.

Then, when the hasty reopening happened and infection raced through the population, millions are believed to have died, though government data has not offered a full accounting.

Repurposing testing booths could play a role in the recovery of urban life and helping communities heal from trauma.

“The retrofitted booths could be very powerful interventions and highly significant ones, if they effectively reverse the security-and-surveillance nature they played in the pandemic and are turned into spaces of communal healing,” said Dr Michele Acuto, professor of global urban politics in the School of Design at the University of Melbourne.

To be sure, these booths may just see temporary reuse, and their long-term role in Chinese urban life remains to be seen.

Some debt-ridden local governments may be reluctant to invest any further into obsolete testing booths due to strained coffers, according to Dr Huang Yanzhong, a professor of global health at Seton Hall University’s School of Diplomacy and International Relations. But he notes that there may still be incentives to convert these booths, including the decentralisation of essential services and if such stalls could help boost employment.

In Hangzhou’s Xiaoshan district, over 170 testing booths in high-traffic areas have been transformed into tourist counters in preparation for September’s Asian Games, delayed from last year due to Covid-19.

Smiling youthful volunteers in red vests staff refurbished pastel-hued kiosks, offering maps, sight-seeing brochures and even bubble tea.

“It’s as though the pandemic never happened,” said Ms Qu. “We all want to forget about it.” BLOOMBERG