In India, fake Singapore profiles are a new front in alleged foreign influence campaigns

Sign up now: Get insights on Asia's fast-moving developments

Those targeted so far are experienced and well-connected journalists and researchers across India who specialise in defence and geopolitical issues.

PHOTO: EPA-EFE

NEW DELHI/SINGAPORE – The offer seemed prestigious.

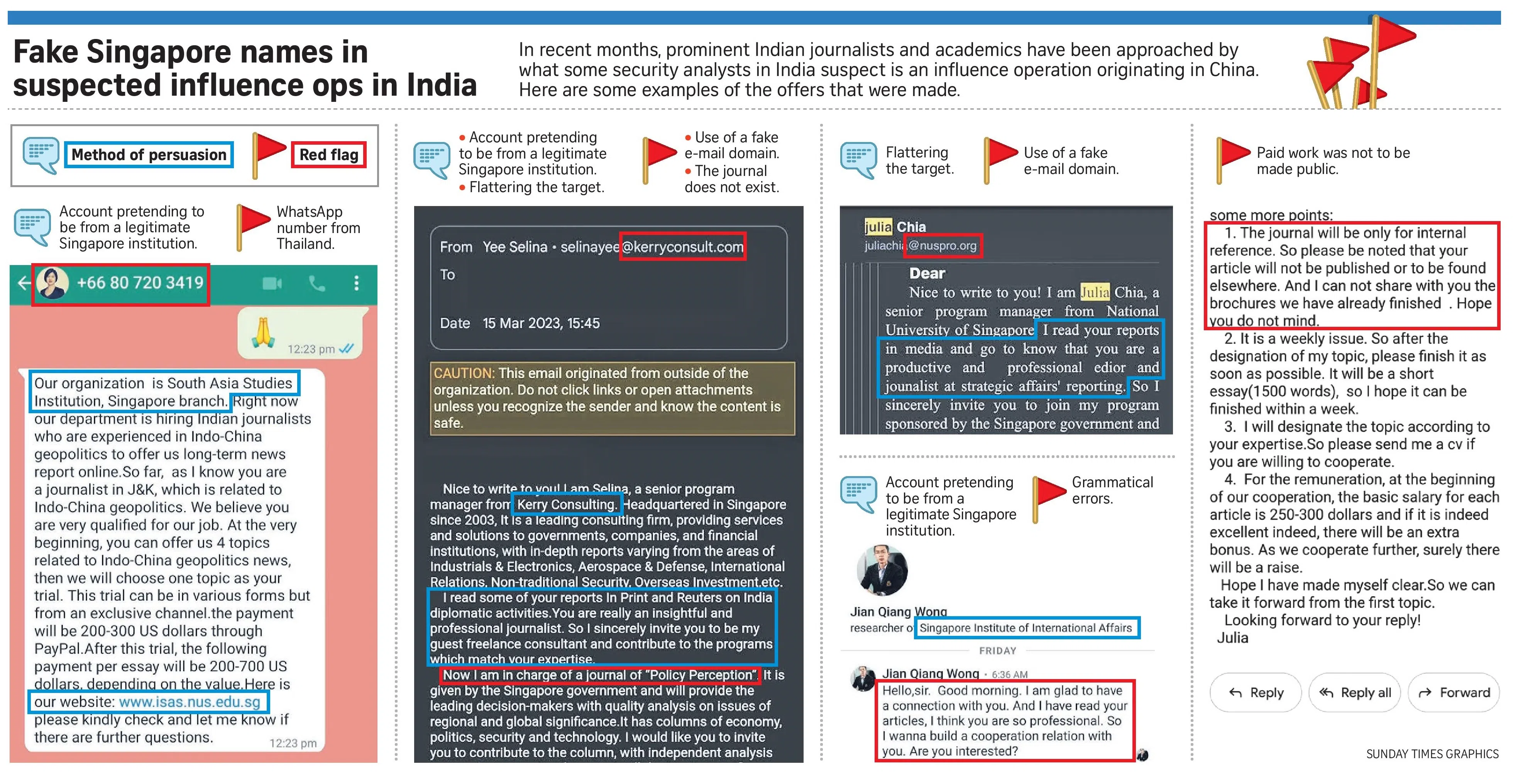

A “senior program manager” claiming to be from the National University of Singapore (NUS) approached senior Indian journalist Aditya Raj Kaul on professional networking site LinkedIn, inviting him to write for a weekly journal.

He would be paid “400 dollars” for each article on assigned topics – well above market rates in India. There would even be a bonus, should his work be “indeed excellent”.

But Mr Kaul, executive editor of national security and strategic affairs at TV9 Network, one of the country’s biggest television news entities, found no mention of the manager – a “Julia Chia” – on the NUS website or in a Google search.

“I realised there’s something fishy, something wrong,” Mr Kaul told The Sunday Times.

There were also other red flags. The journal “Policy Perception”, he was told, is only for “internal reference” and his articles would not be published or found publicly.

He cut off contact with the person.

Mr Kaul, who was contacted in January, believes he was a target of a recent suspected influence operation in India, run largely on social media and personal messaging platforms by individuals claiming to represent Singapore-based institutions such as NUS, the Singapore Institute of International Affairs (SIIA) think-tank, and recruitment firm Kerry Consulting.

All three institutions say the individuals do not work for them and that they do not reach out to potential writers via such means.

Fake Singapore credentials

Those targeted so far are experienced and well-connected journalists and researchers across India who specialise in defence and geopolitical issues.

The modus operandi involved multiple fake employees of Singapore institutions who operate across platforms such as LinkedIn and Twitter, as well as through personal WhatsApp messages and e-mail. It is not clear if they are coordinated.

ST spoke to four journalists who were approached between January and March.

One of them is Delhi-based newspaper Hindustan Times’ foreign editor Rezaul Hasan Laskar, who reported on the operation on March 29 with a colleague.

Unnamed Indian security officials told the paper that the modus operandi was similar to other operations conducted by China in countries such as Australia, Canada and the United States.

On March 10, Mr Laskar received a message from one “Jian Qiang Wong” on LinkedIn, who claimed to be a researcher at SIIA and wanted to “build a cooperation relation” with him.

He ignored it due to several red flags, including the dodgy grammar, but checked with others in media and policy circles to see if they too had received such messages. He found at least a dozen who had been approached by similar “Singapore-based” individuals.

“They were very specifically looking at people who would have access to sensitive information,” Mr Laskar told ST.

The list, he added, included those who work closely with the government, including several serving and retired army officials at a top think-tank.

None of them is known to have responded to these messages.

After the Hindustan Times report was published, some of the online profiles used to approach individuals were deleted.

ST contacted the rest but received no response.

Mr Neeraj Rajput, an independent journalist, was also contacted by “Julia Chia”, first on Twitter and then via a Gmail account in February.

He did not pursue the offer. His suspicions were raised when the e-mail did not come from an official NUS account, but from “ juliachia.nus@gmail.com

Yet another alias used was a “Selina Yee”, who claimed to be from Kerry Consulting, according to screenshots seen by ST.

The e-mail used was “ selinayee@kerryconsult.com

Both NUS and SIIA said the people who approached Indian journalists and researchers do not represent them.

An NUS spokesman said: “There is no such journal in NUS.”

SIIA put up a statement on its website on March 30, saying it does not convey official correspondence over social media platforms.

A Kerry Consulting spokesman said its staff will send e-mails from only the verified www.kerryconsulting.com domain.

“We take fraudulent communication extremely seriously and will be reporting this matter to the Singapore police for further investigation,” he added.

As to why Singapore-based institutions were used in the latest attempts, Mr Muhammad Faizal Abdul Rahman, a research fellow at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), said fake online identities need to appear legitimate and trustworthy.

They would impersonate experts and institutions with brands that inspire trust, confidence and competence. “This is something that experts and institutions in global cities, including Singapore, have,” he said.

Heightened China-India tensions

Security experts in India believe China could be behind this propaganda campaign, citing similarities to previous operations conducted by Beijing and its focus on gathering intelligence about India, with whom it shares an adversarial relationship as well as a longstanding border dispute.

Such attempts, they said, are aimed at shaping public opinion favourably towards China or whichever country is conducting these activities. Another goal could be to gain access to privileged information.

Mr N.C. Bipindra, chairman of Delhi-based think-tank Law and Society Alliance, and an author of a 2021 report on Chinese influence operations in India, said the recent tactics are a “classic example” of how China’s Ministry of State Security, which conducts espionage activities, operates.

“The modus operandi is to try and probe for weaknesses in individuals to see how vulnerable they are to receiving monetary inducements and how that can be exploited,” he added.

Mr Rajput said his extensive experience reporting on India-China border issues could have been why he was targeted.

An Indian intelligence official who asked to remain anonymous due to the sensitivity of the topic told ST it is a Chinese influence operation and “a classic attempt” by China’s United Front Work Department. “They have been found using fictitious organisations and names to lure researchers and journalists especially from South Asia and Africa to write favourable stories,” he said.

When contacted, the Chinese Embassy in India said it does not comment on “alleged messages”.

The Indian government did not respond to a request for comment.

The apparent campaign comes at a time of heightened tensions between India and China, following a border clash in June 2020 that left soldiers dead on both sides. The border dispute continues to be a thorn in bilateral ties.

India’s security agencies have since the clash witnessed a marked uptick in efforts by China to glean information on India, the Hindustan Times’ report cited an unnamed official as saying.

In September 2020, freelance journalist Rajeev Sharma was arrested by Delhi police

The case has made slow progress and the court is yet to frame charges against Mr Sharma, who has denied all allegations and described them as well as his arrest as “political vendetta”.

Mr Sharma’s published writings in Indian and foreign publications pushed a narrative that seemed in sync with China’s interests, wrote Mr Bipindra in his 2021 report.

These include a 2017 piece that argued how India “stands to lose more than it can possibly gain” from the Quad – a security dialogue comprising the US, Australia, Japan and India – which is widely seen as a way to counter Beijing.

Amplifying certain narratives

RSIS’ Mr Faizal, who researches information campaigns, said the tactics used in the latest incidents are not new. Past cases with such a modus operandi include China and Russia, he added.

Malign actors would create fake online identities to approach researchers, journalists and experts to ask them to write opinion pieces.

The objective, he said, is to manipulate these seemingly trustworthy pieces to shape public opinion on geopolitical security issues by amplifying certain narratives on social media and fake news sites.

“What is worrying is that malign actors now could use easily accessible and sophisticated AI tools to generate profile photos and write e-mails. This makes it more difficult to tell what is real and what is manipulated,” he added.

Singapore, too, has previously been entangled in attempts by individuals at undue foreign influence.

Singaporean Dickson Yeo, a former PhD student at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, pleaded guilty to acting within the US as an illegal agent of Chinese intelligence

He had posted a fake job listing on LinkedIn and attracted US military and government employees with security clearances to write reports for him.

Assistant Professor Dylan Loh from Nanyang Technological University’s Public Policy and Global Affairs programme said that countries of all stripes engage in some intelligence, information and influence operations, especially major powers with much larger interests.

While public diplomacy and cultural outreach are generally legitimate activities, they cross a line when they are done illegally, surreptitiously and under false pretences, as is the current case in India, he added.

“Once someone is enticed by the paid work, sunk costs and the commitment will make the target pliable for further cultivation and perhaps deeper, more nefarious kinds of activity,” said Prof Loh.

It was the possibility of getting ensnared in such situations that led the Indian journalists to rebuff the personalities behind this suspected influence operation.

“I was prudent and continue to be prudent about any such messages,” said Mr Kaul.