MIGRANT CRISIS SPECIAL

No good solution to Europe’s immigration crisis

LONDON - Following Europe's refugee crisis is similar to watching a train crash in slow motion: one can see in detail when the policy first went off the rails, everyone knows that the outcome would be a disaster, but nobody seems able to do anything about it.

Europe has experienced migratory pressures for decades, and usually responded by dealing with the symptoms, rather than its underlying causes. A draconian visa regime makes it virtually impossible for Africans and for citizens of many Middle Eastern countries to travel legally to Europe, and a set of secret deals between European and foreign governments ensured that illegal immigration was also kept in check.

The classic deal in this respect was concluded back in 2009 between the then Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi and Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi, under which Libya undertook to stop African migrants from using its shores to navigate one of the Mediterranean's shortest routes to Europe.

But there were also other arrangements: the European Union made it a precondition to any trade deals with its neighbours that those countries should ensure the safety of their frontiers, meaning that they should prevent illegal migration.

All these arrangements collapsed during the Middle Eastern revolutions which came to be known as the "Arab Spring" and in the subsequent bloodshed in Iraq and Syria.

A predictable tragedy

Earlier last year, Europe faced the challenge of boat people from Africa, many of whom drowned in a desperate effort to reach European shores; how many of them perished will remain known only to God and the waters of the Mediterranean Sea. But that was merely a prelude to the tsunami of refugees which engulfed the continent during the second half of 2015.

This was an utterly predictable tragedy.

For the civil war which erupted in Syria in 2011 has killed 250,000 people as well as created an estimated four million refugees. Initially, most of these refugees fled to Syria's immediate neighbouring states: Turkey took in about half of the total, Lebanon admitted 1.2 million, and Jordan accepted a further million. Yet as it always is the case with such crises, the first wave is followed by secondary ones, with refugees spilling further afield.

Europe could not avert the disaster, but had plenty of time to prepare for it. It could have offered more cash to Syria's neighbours to house more refugees on their soil.

Yet although the EU was generous, providing about half of all the international humanitarian assistance to those affected by the Syrian conflict, it was not generous enough: only a total of US$6 billion (S$8.3 billion) was offered by the international community to refugees, and that is just about the same as what Turkey alone spent on housing those who fled from Syria.

More importantly, Europe could have revised its internal arrangements for dealing with migration flows. But frightened of the political backlash which any reform in immigration procedures entailed, EU government stuck to the old rules, which decree that each European state is responsible for dealing with refugees landed on its soil.

A fateful error

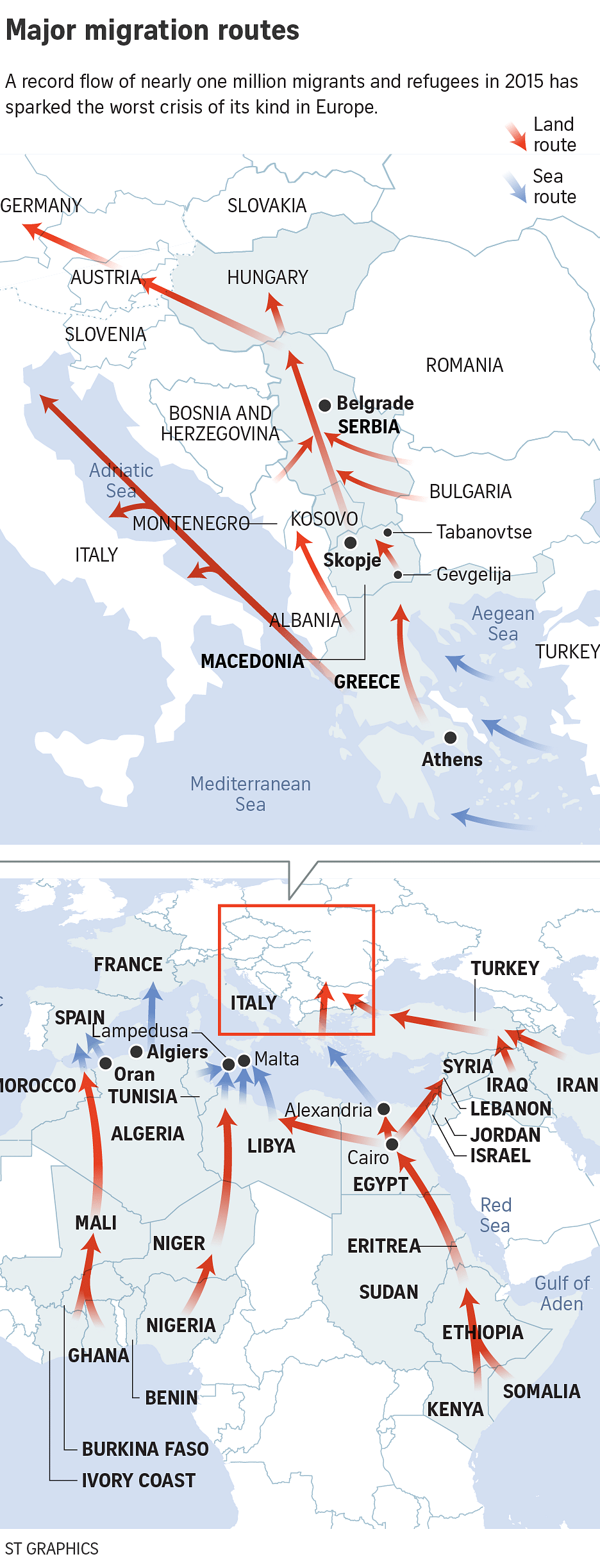

That proved to be a fateful error, for it put all the pressure on Greece and Italy, the two nations in the frontline of migratory routes which also happen to be highly fragile internally. Greece has tottered on the verge of financial bankruptcy throughout this decade.

Swamped by the high numbers of new arrivals and bereft of options, the Greeks and Italians simply tossed aside their legal obligations and allowed the migrants to move on to other European countries.

The result was a disgraceful "pass the parcel" game, in which each European country would turn a blind eye to illegal immigrants, provided they moved on to another European country.

Main railway stations throughout the continent became clogged up with people who had no documents and no income, but who kept on coming from outside the EU at a rate of around 10,000 each day.

And each EU country accused its neighbours of not respecting existing arrangements, while not sticking to the same rules itself.

Yet this was nothing compared to what happened when German Chancellor Angela Merkel announced in early September last year that her country would be suspending existing immigration procedures and admit all asylum-seekers who manage to get to German soil.

The move made her hugely popular with NGOs and the media worldwide but stunned Germany's parliamentarians and leaders of the country's 16 federal states who were not consulted yet were expected to pay for settling all incoming refugees.

And bizarrely, Dr Merkel herself seemed surprised when her offer of hospitality was taken up by no fewer than one million asylum-seekers. Only half of them are actually from Syria; Germany has become a magnet for any other would-be migrant, from all countries further east all the way to Pakistan. And within the space of a few months, what started as a trickle became a flood.

Clearly, Europe cannot go on accepting many more migrants. For not only is the pressure straining existing resources, but the inflow of asylum-seekers is also imperilling all other European achievements. The so-called Schengen agreements under which all controls at the internal borders between most European countries have been abolished is now threatened: barbed wires and border police are reappearing everywhere.

Dangerous rift

The migration flows have also opened up a dangerous rift between the rich western members of the EU who tend to look at the problem in more humanitarian terms, and the poor, former communist East European members of the EU, who regard the refugees as an alien, un-Christian lot, and who are unfamiliar and therefore unsentimental about such migration flows. Europe's current leaders have to slow down this immigration pressure not only to safeguard their own power, but also in order to preserve the EU.

Yet reducing the pressure is not easy. The EU has pledged €3 billion (S$4.5 billion) in aid to Turkey - more than what Europe had given Turkey in a decade - in return for a Turkish promise to close its border with Europe, which is the main gateway for migrants. But that does not seem to have happened: the number of refugees crossing the border has gone down to an average of 4,000 a day now, yet the real explanation may be the wintry weather rather than Turkish measures.

Yet beyond that, there are not many real answers. The war in Syria is unlikely to end soon; more likely, an intensification in fighting during 2016 will increase the number of those fleeing. Stability in the rest of the Middle East is unlikely to come soon either. And Africa may need decades before its developing economies start easing migratory pressures.

Europe's dilemma is that it cannot hope to remain the world's wealthiest continent, surrounded by crises all around, but it also cannot do much about its predicament either. Europe's immigration problem is one which genuinely has no obvious solutions, an emergency which is only containable with partial answers.

Some critics may feel good about taking the high moral ground, but for European governments, the real task is to pick between a set of fairly unpalatable alternatives, in the hope of choosing the least bad one.

Join ST's Telegram channel and get the latest breaking news delivered to you.