Low Jarn May is a born storyteller.

It is evident in the way she relates events and incidents in her life; she punches the proceedings up with dramatic pauses, facial gymnastics, wild gesticulations, witty similes and artful climaxes.

And she does it without uttering a single word.

The 43-year-old is Deaf. The capital letter, she says, denotes a community proud of their Deafness, and sees it as a difference, not a disability. Although it is meant to be politically correct, the term "hearing-impaired" is now considered an outdated, and even offensive, collective label for people with hearing loss.

Ms Low lost her hearing at three, after suffering a high fever.

It broke her parents' hearts, but it did not suppress or extinguish her go-getting, high-achieving spirit.

Today, the assistant director of finance in a government body is probably Singapore's only deaf chartered accountant, one who also has a master's in global finance from the University of Manchester.

Lively and articulate, she is the elder of two children of a TCM practitioner and his wife.

All was well until her illness.

Her mother took her to a doctor who prescribed her a fever syrup.

"The fever continued for a week before I got well," she says through a sign language interpreter.

Sadly, her hearing nerves were damaged in the process. Her mother found out only when she called out to her while cooking in the kitchen one day.

"I was in the living room playing with my toys and didn't respond. She came closer and called out louder and I still didn't respond. She went to my left, and right, and shouted and it was the same. It was only when she stood in front of me that I looked up and smiled."

Her parents took her to the now defunct Toa Payoh Hospital, where a doctor confirmed that she had lost her hearing.

"My parents couldn't accept it. They took me to other hospitals, but at every hospital, the diagnosis was the same," says Ms Low, adding that her maternal grandmother told her devastated parents not to cry over spilt milk and focus their energies on raising her.

Her father took up the gauntlet.

He found out all he could from different outfits, including the Singapore Association for the Deaf (SADeaf) and was advised to learn sign language.

He did, and then took it upon himself to teach his daughter, starting with food items.

She recalls: "You know how children have short attention spans, can't sit still and love food? I soon worked out that if I followed what he did, I would get what I wanted."

Her father did not stop there with her, but taught his wife and the neighbours too.

"He didn't want me to feel left out when I was playing with the neighbours' children. I grew up happy and didn't feel discriminated against," says Ms Low, who grew up in a one-room flat in Lorong 5, Toa Payoh.

Her resourceful father also enrolled her in a pre-school for deaf children at St Andrew's Cathedral, run by a group of expatriate housewives.

"It was Montessori mixed with sign language. I played and learnt a lot," says Ms Low.

She did well at the School for the Deaf in Mountbatten Road, scoring 245 for her Primary School Leaving Examination with no tuition.

"My parents couldn't afford it. But my teachers didn't write me off," she says simply.

Life took a nasty turn when she was 11. Her father, who was from Kuala Lumpur, died in a car accident on one of his trips to the Malaysian capital.

"One of the biggest regrets of my life was that I didn't get to say goodbye. Many of us take our parents for granted," she says.

Her mother, who had been a homemaker, had to find work as a freelance tour guide to raise Ms Low and her younger brother.

"My brother and I were latchkey kids. Thankfully, we had a lot of relatives who helped. My mother had 10 siblings and many of my uncles and aunts took turns to drop by."

The loss of her father forced her to become independent at a young age. The former student of Mount Vernon Secondary worked hard so that she could earn scholarships to ease her mother's burden.

She did well enough to go to a junior college, but decided to take the polytechnic route instead.

Although she had secured a place to study information technology at Ngee Ann Polytechnic, that plan got derailed when her best friend Shalini Gidiwani persuaded her to make a life-changing switch to accountancy instead.

A key turning point in her life occurred in 1994, when a staff from SADeaf - where she worked during her semester breaks - encouraged her to attend the inaugural World Federation of the Deaf youth camp in Austria.

Ms Low was eager, but there was a stumbling block - she could not afford the $2,000 needed for the trip.

When her polytechnic counsellor learnt about it, she not only told her to go, but also found sponsors for her air ticket and expenses.

The camp opened Ms Low's eyes.

"I learnt so many things. I learnt about Deaf pride and women empowerment. I learnt that the Deaf can do everything except hear. I met some young people who were doing their masters and PhDs in prestigious universities, not just Gallaudet," she says, referring to the Washington university for the deaf and hard of hearing.

She also met accomplished deaf professionals, including social workers and doctors.

"It was also my first time seeing gay guys and gals. Guess what, two gay guys saved me from a hot-blooded Italian," she quips.

Besides opening her eyes, the camp demolished the inferiority complex she had sometimes felt because she could not hear, and instilled in her a deep sense of pride.

"I found my identity," she says.

Upon her return to Singapore after the camp, she fell ill. Her new confidence came to the fore and she insisted, for the first time, on going to the doctor alone. Her worried mother followed her from a distance.

At the clinic, she happened to see what the doctor was scribbling into her medical records.

"My eyes nearly popped when I saw what was written on a white label: deaf and dumb," she says.

She indignantly took the doctor to task and even asked him to write a memo to his colleagues reminding them to be sensitive to how they refer to their patients.

In more ways than one, she says, the camp started her on a wondrous trajectory, one which took her around the world and led her to meet movers and shakers from all communities. "If I hadn't attended the camp, I think I might be an apathetic member of the Deaf community," she says.

Egged on by her friend Shalini, she became a passionate advocate for deaf language and education rights.

She started out volunteering with SADeaf's Adult Outreach programme, teaching illiterate deaf adults basic English and other skills. She moved on to tutor deaf students in subjects like mathematics and principles of accounts and also taught sign language.

Her passion later led her to serve on the SADeaf's executive council. Among other things, she chaired its linguistic sub-committee and founded Youthbeat, its youth volunteer arm.

Championing causes for her community took her around the world. Highlights include representing Singapore at the World Federation of the Deaf (WFD) Asia-Pacific meetings and WFD Congress in Brisbane, Australia, in 1999 and the International Forum on Disabilities in Osaka, Japan, in 2002.

In 2015, she found herself at the UN headquarters in New York for the eighth session of the Conference of the States Parties, attending the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

Her career grew alongside her advocacy work.

Because of her bubbly personality and industry, her polytechnic lecturer and counsellor helped her to secure auditing jobs after she graduated in 1996.

She did not rest on her laurels and studied part-time for her Association of Chartered Certified Accountants (ACCA) credentials.

She completed it in 41/2 years, with a one-year break when she got pregnant after marrying senior draftsman Francis Tang, who is also Deaf, in 2001.

A 10-day working trip to Shanghai was the impetus, she says.

Then working for a local marine company, she saw how hungry Shanghainese workers were.

"Two of my Chinese colleagues went for courses - German, ACCA - every day. I foresaw that they could take over my job. That scared me and I worked hard to complete my ACCA."

ACCA Singapore's PR and marketing manager Regina Yeo says: "Completing the course in 41/2 years is very, very good. Some have taken 10 years, some even fail the same paper 10 times."

Before joining the public sector two years ago, Ms Low worked in managerial and senior positions at corporations, including electronics giant Gain City, where she headed a team of 20.

"I've been lucky because I've met the right people at the right time, people who see beyond my disability," she says.

It was not always smooth-sailing - there had been instances where colleagues had doubts about her ability because she cannot hear.

"You just have to lead by example. I work, and then I show them how," she says.

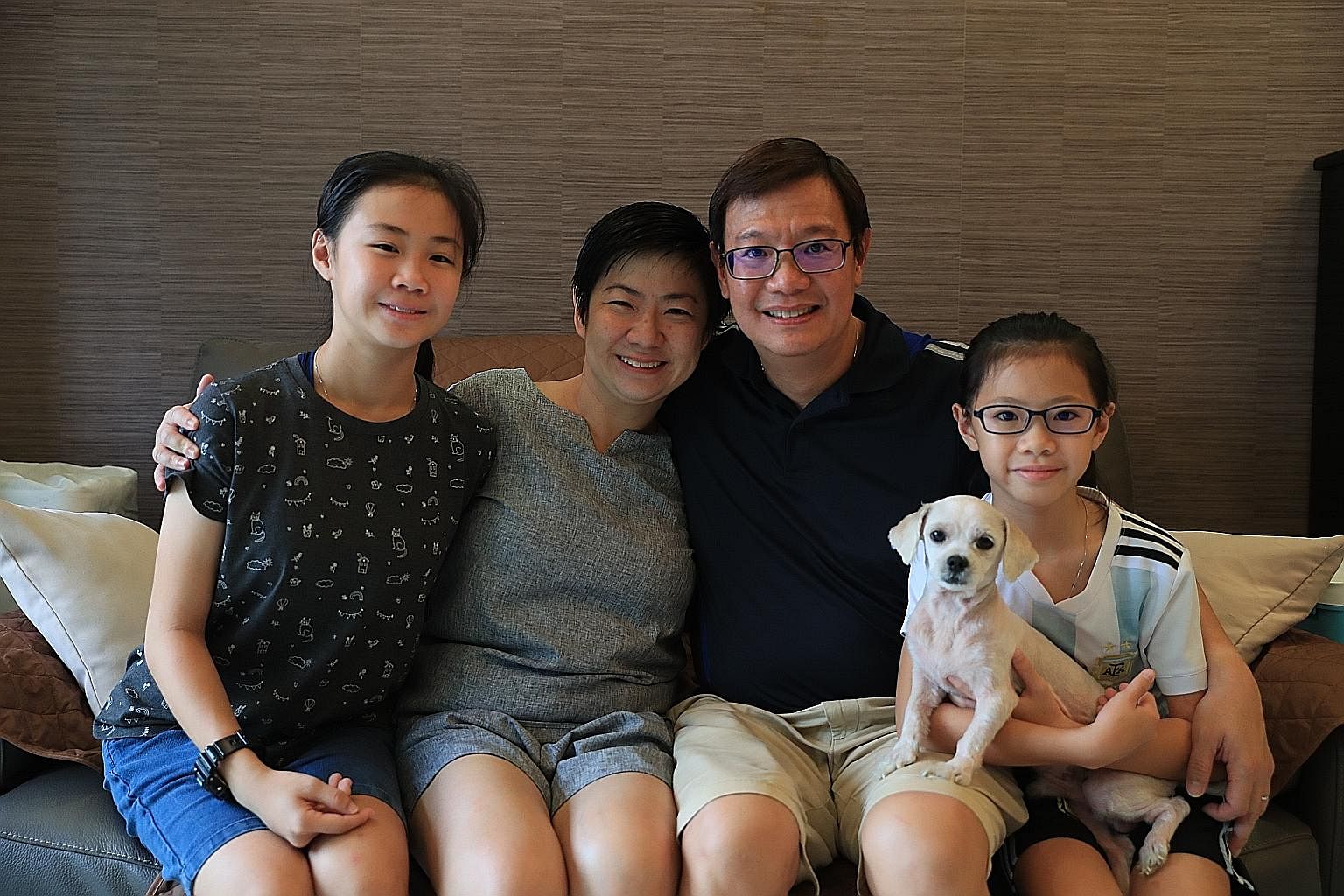

The mother of two daughters, aged 10 and 15, is often asked how she juggles motherhood with career and advocacy work.

"It just happened naturally," she says. "It's the same for everyone, isn't it? When something needs to be done, you'll know what to do."

Ever practical, she has never indulged in self-pity and "what if" exercises.

The ardent fan of Bungee Dance - a workout routine where participants are hooked to a bungee cord from a harness - reckons she would still be the same person if illness had not robbed her of her hearing.

"I think what I am today is a combination of perseverance and tolerance, and other factors like values passed down from my family. I'm also blessed to have met, along the way, wonderful people who had faith and belief in me."