News from the Middle East is dominated by stories of nations breaking up or states convulsed by domestic turmoil. Yet there is one country bucking this vicious circle: Turkey is not only growing in regional influence but also has serious aspirations to global-power status.

It was Turkey's recent decision to commit troops to the civil war in neighbouring Syria that shifted America's own strategy in that conflict. The US Air Force will now intensify its sorties against terrorists belonging to the so-called Islamic State in Iraq and Syria by using the strategically critical airbases on Turkish soil, with other Western nations likely to follow suit.

And if Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan's recently concluded tour of Asia is an indication, his national vision is aiming far higher. Mr Erdogan signed a "strategic partnership" agreement with China, vowed that Turkey will "defend" Pakistan, touted weapons sales to Indonesia and even seriously raised the possibility during a joint press conference in Jakarta with President Joko Widodo that Turkey may apply to join Asean.

Of course, some of this is typical macho grandstanding stuff of the kind that goes down well with domestic audiences in the Middle East, but is of little practical consequence. Mr Erdogan must know that, if only due to the accident of geography, Turkey has scant chance of joining Asean.

Still, the emergence of Turkey as a global player, a country which is ready to deploy both its military and economic assets on a worldwide basis, is a reality. But so are some of Turkey's internal vulnerabilities, which may hold back its aspirations.

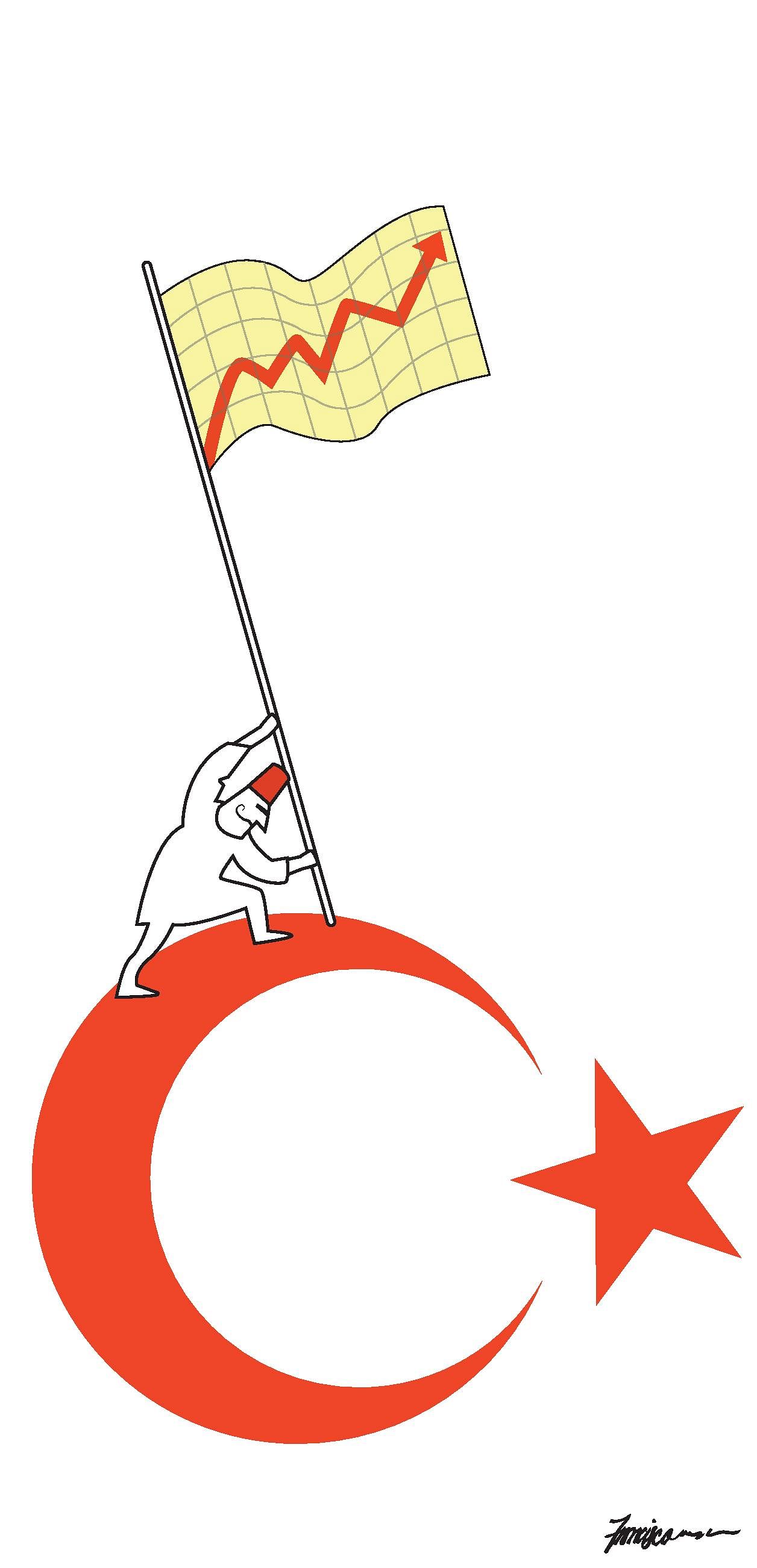

GROWING FAST

Turkey's domestic achievements are remarkable. Since 2003, when Mr Erdogan first came to power as prime minister, the country has almost tripled the size of its gross domestic product, from US$303 billion to US$820 billion (S$1.1 trillion). Turkey's economy is now the 17th largest in the world, slightly ahead of Australia's if the more accurate purchasing power parity calculation is used.

Other indicators tell a similar story. At the start of the new century, average income among Turkey's 77 million people was less than 20 per cent of that in the European Union, the organisation which Turkish leaders like to compare themselves with. Last year, Turkey's average income was closer to 70 per cent of Europe's. At this rate, the gap between Turkey and the rest of Europe could be largely erased by 2030, an achievement that would put an end to centuries of decline and under-development, when the Ottoman Empire - from which modern Turkey emerged - used to be derisorily dismissed as "the sick man of Europe".

The enormous boost to national confidence that such a performance engineers is everywhere. More than 15,000 Turkish firms are now doing business on global markets. Turkish Airlines, the country's flagship carrier, operates to over 200 destinations on four continents.

Turkey is also opening embassies everywhere. Former Turkish foreign minister Ahmet Davutoglu, who has since become prime minister, used to take great pride in colouring red every new country into which his diplomatic network expanded. He once joked with British officials that he had chosen red because that was the colour the British used on maps to indicate their colonies. And in terms of firepower, the Turkish military is among the 10 most significant formations in the world, with defence expenditure increasing by more than 9 per cent in real terms each year.

Nor should one ignore Turkey's huge "soft power" - the country's appeal to its neighbours. It is widely admired as an Islamic state that has succeeded in blending adherence to the faith and Islamic social values with economic progress, the promotion of women and political stability.

It has also been an amazingly welcoming place for refugees: In the past half-century, the country became home to an astonishing six million refugees from the Soviet Union, Yugoslavia, Iraq, Iran and Azerbaijan. It is also now home to an estimated 1.7 million refugees from Syria. In the Middle East, Turkey is seen as a haven of prosperity and safety.

PROBLEMS WITH NEIGHBOURS

To be sure, with such dizzying success also came some serious foreign policy setbacks. Turkey's avowed aim of having "zero problems" with all its neighbours is now remembered as a sad joke, since the Turks now have problems with almost all their neighbours.

Mr Erdogan's claims to have a superior understanding of the Middle East were also disproven, since he was just as surprised as leaders elsewhere by the wave of revolutions that erupted in the region in early 2011 and came to be known as the Arab Spring. And, like most Western governments, the Turks also ended up backing the wrong horses. They supported the Muslim Brotherhood government in Egypt, only to see it overthrown by the Egyptian military. They backed the Hamas Palestinian organisation, only to incur the wrath of Saudi Arabia and other moderate Arab nations. And they are just as clueless about what can be done with Syria as are all Western governments.

Still, the Turkish leader has succeeded in reversing these errors, largely because the countries of the Middle East now need Turkey more than Turkey needs them. Mr Erdogan has carefully - and often without saying much in public - cast himself as a defender of Sunni Muslims against the Shi'ite challenge from Iran; Saudi Arabia now sees Turkey as a regional linchpin. After a long period of dithering, he has also swung behind the Western-inspired alliance to defeat the Islamic State terrorists. Mr Erdogan has even tamed his baiting of Israel, which served him so well in the past to burnish his Islamic credentials.

And his global ambitions remain untamed. Mr Erdogan brushed aside domestic concerns about the alleged maltreatment of ethnic Uighurs in China and went ahead with his recent visit to Beijing, proof that Islamic governments are quite capable of ignoring the plight of other Muslims when they deem this convenient.

But China repaid the compliment by showing respect for Turkey's growing power. Beijing has studiously ignored Mr Erdogan's previous outburst when he publicly accused China of pursuing "almost genocide" against the Uighurs, and the Chinese have also pretended not to notice the daily demonstrations outside their embassy in Ankara, the Turkish capital. Like the West, the Chinese are finding the Turks difficult, but necessary.

Can anything interfere with Turkey's steady rise to global power status? Yes, plenty. First, although economic performance has been good, it's not stellar. Growth has slowed down considerably. Ominously, Turkey suffers from a chronic current account deficit as imports grow faster than exports. This is made worse by the fact that ordinary Turks save very little, so deficits have to be financed from foreign funds, which are usually short-term portfolio investments, looking for quick profits. In short, Turkey is less immune to global economic downturns than its leaders would have us believe.

More importantly, the policy pioneered by Mr Erdogan of replacing Turkey's secular and inclusive national identity with a new nationalism based on Islam offers little to the country's minorities, such as the various ethnic groups from the Caucasus, or the Alevites, also known as "Qizilbash", which means "the red-headed ones", Turkey's own "ang mohs".

The most serious situation concerns the Kurds, who make up 15 per cent of the population and who may be on the verge of relaunching a violent rebellion against the authorities unless the government offers political concessions to their autonomy demands.

And then, there are the politics of the country. For although Mr Erdogan has rightly claimed credit for upholding stability, he may be about to destroy his own creation. Turkey has been without a new government since Mr Erdogan's ruling party lost its overall majority in the general election held in early June. The suspicion is that Mr Erdogan refuses to form a coalition with opposition parties because he wants to order a new snap election soon. The idea that ballots should take place frequently until the "correct" result is produced will not chime well with Mr Erdogan's repeated claim that Turkey is the only functioning democracy in its region.

But there is no doubt that, on the whole, the rise of Turkey has been beneficial. Nor is there any question that Turkey's ability to drag itself from the Third to the First World acts as an inspiration for other Muslim states.

But the Turks are about to discover the lesson which every rising power ultimately confronts: That nothing destroys the dream of progress more than hubris - an excessive and often misleading belief that one's capabilities are endless.