When it comes to the elderly, it seems as though one doctor is rarely ever enough.

Take Madam Loh Kwai Fong, 74, who has a chronic lung problem that leaves her breathless, a heart condition and problems with her kidneys. Her blood pressure is high and she has difficulty walking.

"I used to go in and out of hospital because of these problems," said the retired shoemaker. "I would see many different doctors."

Many elderly Singaporeans will, like Madam Loh, experience several years of ill health. The average person lives to 82, but experiences eight years of ill health in their old age. The population of seniors is also rising rapidly and is expected to hit 900,000 by 2030.

But having patients with multiple health conditions shuttle between different specialists is not ideal, and several experts have come out to say as much.

During an interview with The Straits Times in July, the deans of Singapore's three medical schools stressed the importance of training more "generalist" doctors. This refers to specialists in fields such as geriatrics or internal medicine, where the focus is typically on the patient as a whole - rather than a specific organ or body part.

And in a speech last month, the Ministry of Health's (MOH) director of medical services Benjamin Ong urged medical students to consider family medicine as a career. In this field, doctors are trained to manage all kinds of patients - with different ages and health issues - outside the hospital.

"Increasingly, I think that's what we need in the health system - we need generalists," said Associate Professor Yeoh Khay Guan, who is dean of the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine at the National University of Singapore. "It's not very good if our elderly parents see five doctors. It's better if there's also a generalist to look after their needs." The generalist doctor would then be the one in charge and he would call in specialists if there was a need, so the patient would not have to deal with too many doctors.

In some ways, there has been progress. Internal medicine, for example, is among the top three specialties with the biggest growth. In 2012, there were just 94 specialists in this field. By last year, this number had grown to 141. In that time, the number of geriatric medicine specialists also grew from 67 to 89 - an increase of 33 per cent.

Even so, policymakers continue to articulate the need for more young doctors in these fields. But what is preventing them from joining up in the first place?

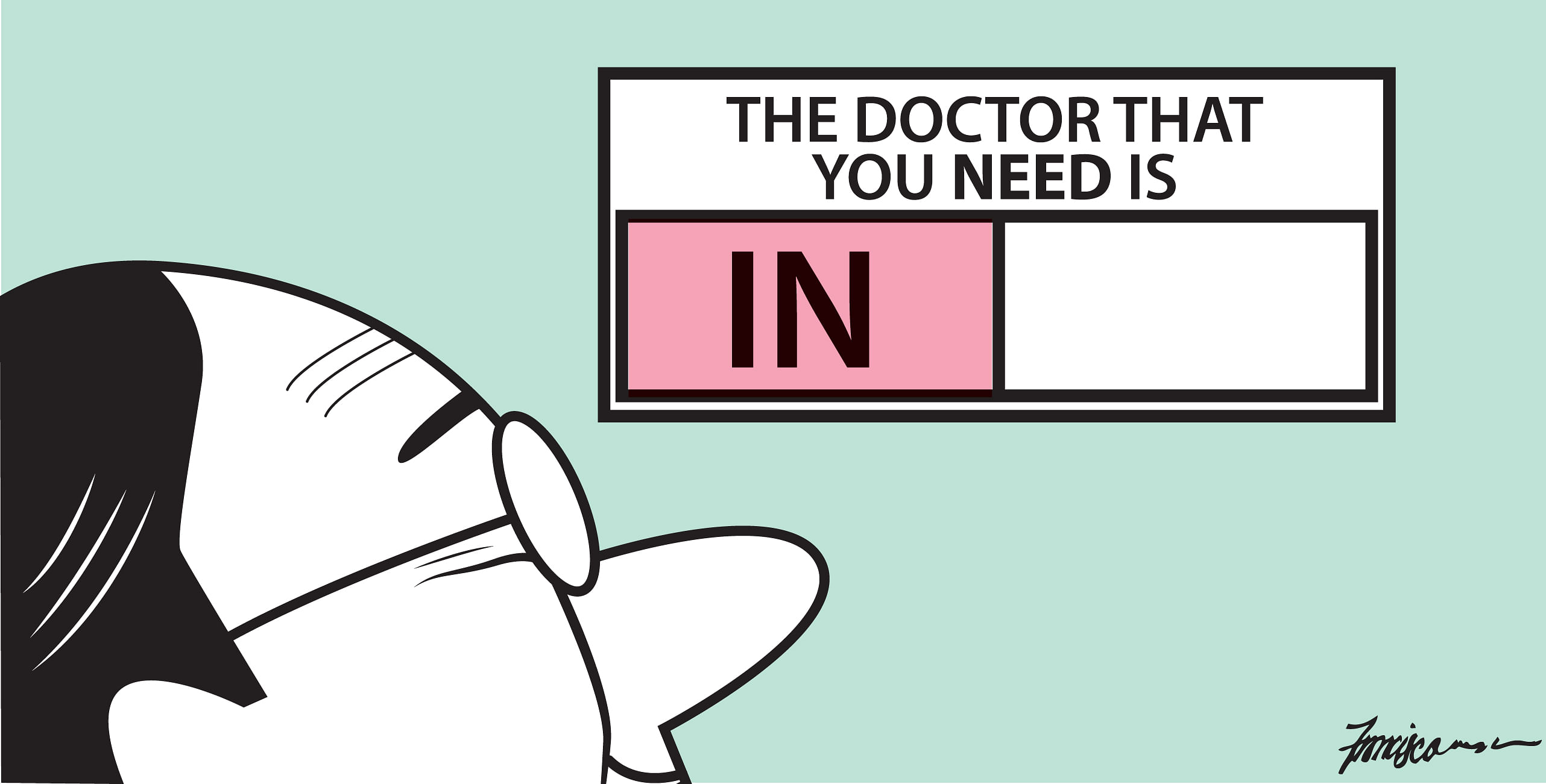

WHAT'S IN A NAME?

There is a certain glamour attached to the word "specialist" - and conversely, an implicit bias against the "generalist" who is assumed to be a jack of all trades. Ask any patient, said healthcare consultant Jeremy Lim, and chances are that they would rather consult a specialist for their health problems, if they can afford it. That is only natural. After all, who would not want to approach a certified expert in the area in which one needs help?

"The language that is used biases patient preferences towards the specialist-driven model," pointed out Dr Lim, a partner in Oliver Wyman's global health practice. "But by definition, specialists think about specific issues, and so they do have blind spots."

Typically, Dr Lim said, specialists deal only with problems within their area of expertise. When the need arises, the patient is referred to yet more specialists. "Nobody wants to be responsible for anything outside their area of specialisation... and so you need multiple specialists," Dr Lim said.

This shuttling between different doctors can translate to multiple clinic visits, a larger overall bill, and a confused elderly patient. In contrast, generalists are trained to manage all these conditions in a single person, as a whole.

"We deal very intimately with all the issues that the elderly face. We don't look at these in silos, on their own," said Dr Sabrina Lau, who is a senior resident in the National Healthcare Group's geriatric medicine residency programme.

She does not believe that her chosen area of expertise commands any less reputation or respect. "But to put it bluntly, the work that we do is not flashy and sometimes it can be more behind the scenes," she said.

Perhaps one way to encourage more young doctors to join these "generalist" fields is to raise awareness of the work they do, suggested Dr Loke Wai Chiong, who is healthcare sector leader for Deloitte South-east Asia. He recalled how a decade ago - when he was running medical manpower for one of the public healthcare clusters - it was a "constant challenge" getting people to opt for these less popular career tracks.

"Some ways (to get them interested) may be to celebrate and tell the stories of the unsung heroes who solve intricate problems of care, rather than just dispensing the newest drugs," he said.

MAKING THE HARD DECISIONS

Another problem is that junior doctors may not have the opportunity to see what these "generalist" fields are truly like. With more than 30 specialties to choose from and only around five years in medical school, it is not always easy for a fresh graduate to know what specialty suits him best.

In the past, said Dr Tan Wu Meng, who is a Jurong GRC MP, young doctors could rotate through a series of postings after completing their first year as a house officer. "This could be a mix of hospital medical and surgical postings, or a family medicine posting," explained Dr Tan, who is an oncologist by training. "Junior doctors would accumulate experience while deciding what path to take, and which training programme to apply for."

The trade-off under this model was career advancement - because of the meandering path that many young doctors took, completing specialist training often became a longer process which would take at least seven years. These days, the road towards becoming a specialist is a more direct one, with junior doctors committing to a specific programme. According to the MOH Holdings website, it takes four to six years to become a full-fledged specialist.

"These through-track training programmes provide a more direct path to completing specialist training," Dr Tan said. "But it also means the self-discovery journey is shortened, and with it the opportunities for a more diverse experience."

Perhaps there is something that can be done to introduce more diversity in medical training, while keeping the existing model intact.

The impact of exposing junior doctors to role models in a particular field of study cannot be underestimated, said Professor Thomas Coffman, who is dean of Duke-NUS Medical School. "As these specialties grow, (medical students) can see how compelling these areas are," he said.

Studying geriatric medicine in a classroom is one thing; watching senior doctors apply that knowledge to an elderly patient is something else altogether. "One way may to be appeal to the intellectual challenge of dealing with complex mutually-interacting conditions," Dr Loke said.

A THIRD WAY

But failing a change in attitudes or to the training structure, what else can be done? One way is to upskill other health professionals to shoulder some of the load, suggested Dr Chia Shi-Lu, who chairs the Government Parliamentary Committee for Health. He gave the example of how some hospitals overseas have introduced "hospitalists" - who may be highly trained nurses - to care for a single patient.

Another is to introduce a new role, suggested Dr Tan - that of the coordinating physician who serves as the link between patients and specialists. "Specialty departments, by nature, are optimised towards looking deeply but narrowly. So we need the coordinating physician to look at the holistic picture," he said.

For if a patient must see five doctors, there should be a way to make sure at least one of them can see the big picture.