It is easy to see why outgoing president Barack Obama's team told their incoming Trump administration replacements that the most urgent national security challenge they would face after the inauguration would be North Korea.

Right on cue, North Korea's President Kim Jong Un, in his New Year address, boasted that his regime was close to testing an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) which could mount a nuclear attack on American cities.

South Korean and US intelligence agencies take him seriously, and have noted signs that a test may be imminent. It could come at any time. If so, it would mark a whole new phase in the development of North Korea's nuclear forces, increase the potential for instability on the Korean peninsula and beyond, and underline the complete failure of US-led efforts stretching back over more than 20 years to avoid exactly this outcome.

Of course, a test - even a successful one - would not in itself give Pyongyang an operational capability. But time and again, North Korea's engineers have shown an ability to bring systems into service faster than outside observers expect, and the prospect of operational ICBM forces within a few years would start to change perceptions and behaviour even faster.

What would that mean?

One obvious concern is that a nuclear-armed ICBM force would give North Korea's leaders the capacity to launch an unprovoked nuclear attack on American cities. That could never be a sane option for Pyongyang, because swift and devastating American retaliation is so certain. So, this is a danger only if North Korea's leaders - or whoever has control of its weapons - are unhinged. That's far from impossible, but not the biggest risk.

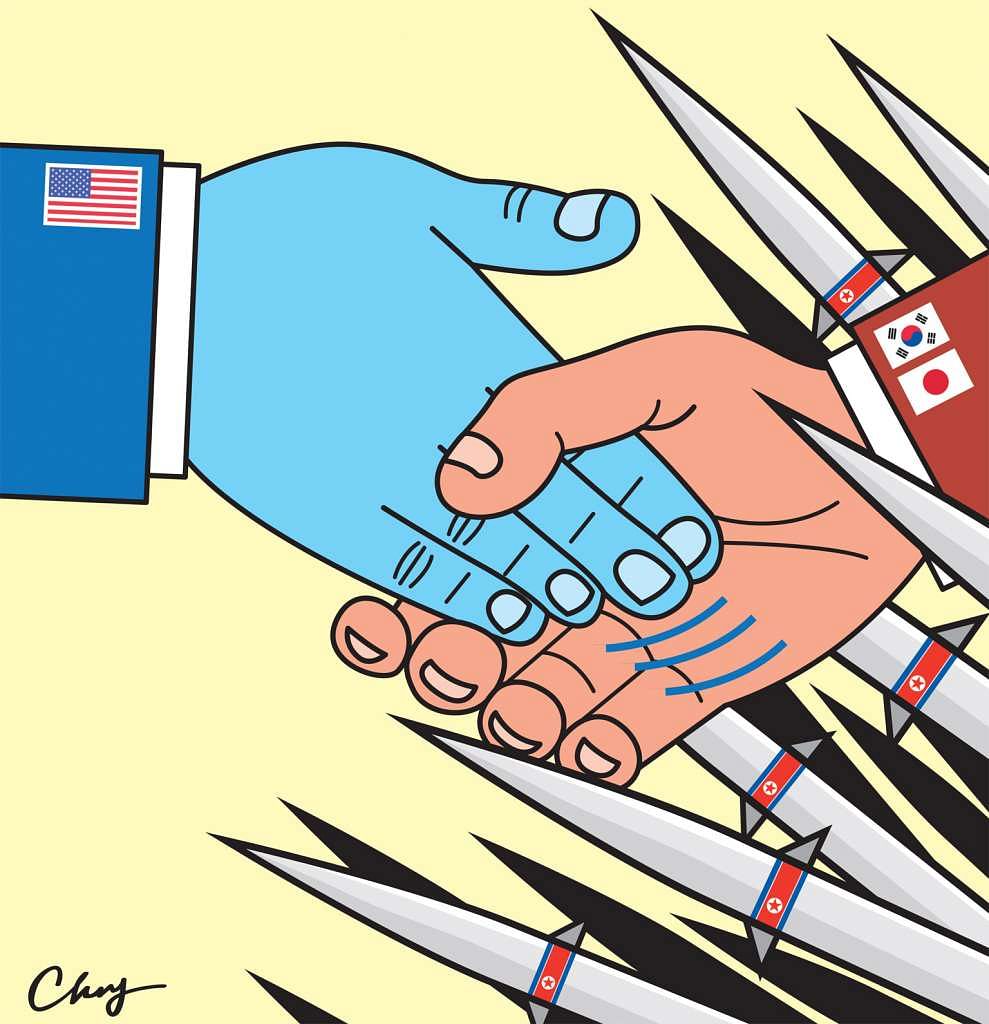

A much more serious danger is that a North Korean capacity to target the US directly with nuclear weapons could prevent America from responding to North Korean aggression against South Korea or Japan. Most worrying from Seoul's and Tokyo's point of view is the possibility that Pyongyang might try to force concessions by threatening them with a nuclear attack.

Such a threat would become much more credible if and when Pyongyang deploys operational ICBMs. Without nuclear forces of their own to deter a North Korean strike, Seoul and Tokyo must rely on America to neutralise a North Korean threat by promising to retaliate in kind for any nuclear attack on its allies. But Seoul and Tokyo would legitimately fear that America's promise to retaliate would not be credible if North Korea could realistically threaten counter- retaliation against US cities.

They would also fear that America would become less reliable in supporting them against non-nuclear military threats from North Korea. Before committing US conventional forces to combat North Korea, any US president would have to weigh carefully the possibility that even a small clash might escalate into a nuclear exchange.

So, a North Korean ICBM force would make America more cautious, and less reliable, in supporting its north-east Asian allies across the spectrum of threats.

And that, of course, has implications that go far beyond the North Korean issue itself. By undermining the credibility of America's alliances in Asia, a North Korean ICBM capability would weaken the entire US strategic posture in Asia. It would strongly encourage both Japan and South Korea to consider developing their own nuclear forces instead of relying on the US. That would allow them to neutralise a North Korean nuclear threat directly themselves.

It is hard to see how America's alliances with these countries could survive if they develop their own nuclear forces, and it's hard to see how America's leading strategic role in Asia could survive if these alliances do not.

So, this is the problem that President Donald Trump faces as he takes office.

He has made it worse in some ways. His America First rhetoric - and his remarkable suggestion during last year's election campaign that South Korea and Japan should build their own nuclear forces - plainly suggests that he is less willing to run risks, including risks of nuclear attack, to support allies when America itself is not directly threatened. That is just what Seoul and Tokyo fear, and Pyongyang hopes.

Nonetheless, earlier this month, Mr Trump tweeted in response to Mr Kim's North Korean ICBM test: "It won't happen!"

One wonders what he thinks he can do to stop it. Since the early 1990s, successive US presidents have made it one of their top priorities to stop Pyongyang from developing nuclear weapons and the means to deliver them, above all, against the US itself.

Direct military action has long been ruled out because of the risks of sparking a wider war in which South Korea, and perhaps Japan, would suffer terribly, and diplomacy backed by economic incentives has proven fruitless. That leaves economic sanctions, which have been ineffective, in part because China, as North Korea's most important economic partner by far, has been, at best, half-hearted about imposing and implementing them.

President Trump may think he can change that by pushing Beijing to become much tougher on Pyongyang. But he'll find Beijing hard to shift: Chinese leaders are cautious about steps which might undermine North Korea's government and unleash a chaotic regime collapse on China's border.

And they may well realise that a North Korean ICBM that weakens US alliances in Asia can benefit China in the long run as it seeks to build a "new model of great power relations".

That is a reminder that though North Korea might be the most urgent issue on the new US President's national security agenda, it might not be the most consequential in the longer term.

North Korea is, after all, an economic basket case. China, on the other hand, has a good chance of overtaking America to become the biggest economy in the world while Mr Trump is president.

• The writer is a professor of strategic studies at the Australian National University in Canberra.