Is coffee good for my health? Should I eat less carbohydrates and more protein? How much exercise is sufficient to keep me healthy?

We know it pays off health-wise to make the right diet and lifestyle choices, but it is not easy sieving out fact from fiction amidst the myriad of oft contradictory and inconsistent research reports.

Research should empower individuals to take personal responsibility for their health by making sound evidence-based lifestyle and diet choices. And this evidence is often derived from population studies such as cohort studies. A "cohort" is a group of people who share a common trait, for example ethnicity, gender or occupation. Cohort studies attempt to observe such a group over a long period, collecting data such as physical, biological and lifestyle information, which is thought to be relevant to the disease risk.

Unlike interventional trials, cohort studies do not involve the administration of drugs and participants are not asked to make any change to their diet or lifestyles. Nevertheless, cohort studies with large numbers of participants and long periods of observation are very informative, often providing critical evidence on how risk factors drive disease rates in a population.

There are many successful cohort studies based on Western populations. One such example is the Framingham Heart Study, which started in 1948 with 5,209 participants. Almost every important fact we know about the causes of heart disease and stroke can be traced back to this study. Another example is the British Doctors Study, which began observing 40,701 British doctors from 1951 and has continued for more than six decades. It was the first study to show convincing links between smoking and deaths from lung cancer, heart disease and lung diseases.

How would such findings apply to Asians since we are distinctly different in genetic make-up, lifestyle and diet? For example, an Asian tends to have more body fat compared with a white European of the same body mass index (BMI), and this has implications on using BMI as a predictor of disease risks. Another example is the difference in staples - rice versus bread or potatoes. This too will impact how the health effects of carbohydrates is translated for Asians.

Asian populations are under studied. Recognising this need, the United States' National Cancer Institute (NCI) sponsored a collaborative effort between the University of Southern California and the then Department of Community, Occupational and Family Medicine (now NUS Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health) to establish the Singapore Chinese Health Study (SCHS) cohort in 1993. The NCI continues to fund the study today.

Now more than 20 years into the study, SCHS has published 220 papers, with most of the work receiving much scientific interest and cited extensively worldwide. The term "Singapore Chinese Health Study" alone generates over 26,000 hits on Google for its noteworthy findings. These include several significant and novel findings that have produced important insights to shape our understanding of associations between diet and disease in Asians, including:

•Eating fish frequently may reduce the risk of breast cancer, probably due to the protective effect of omega-3 fatty acids, which are high in fish.

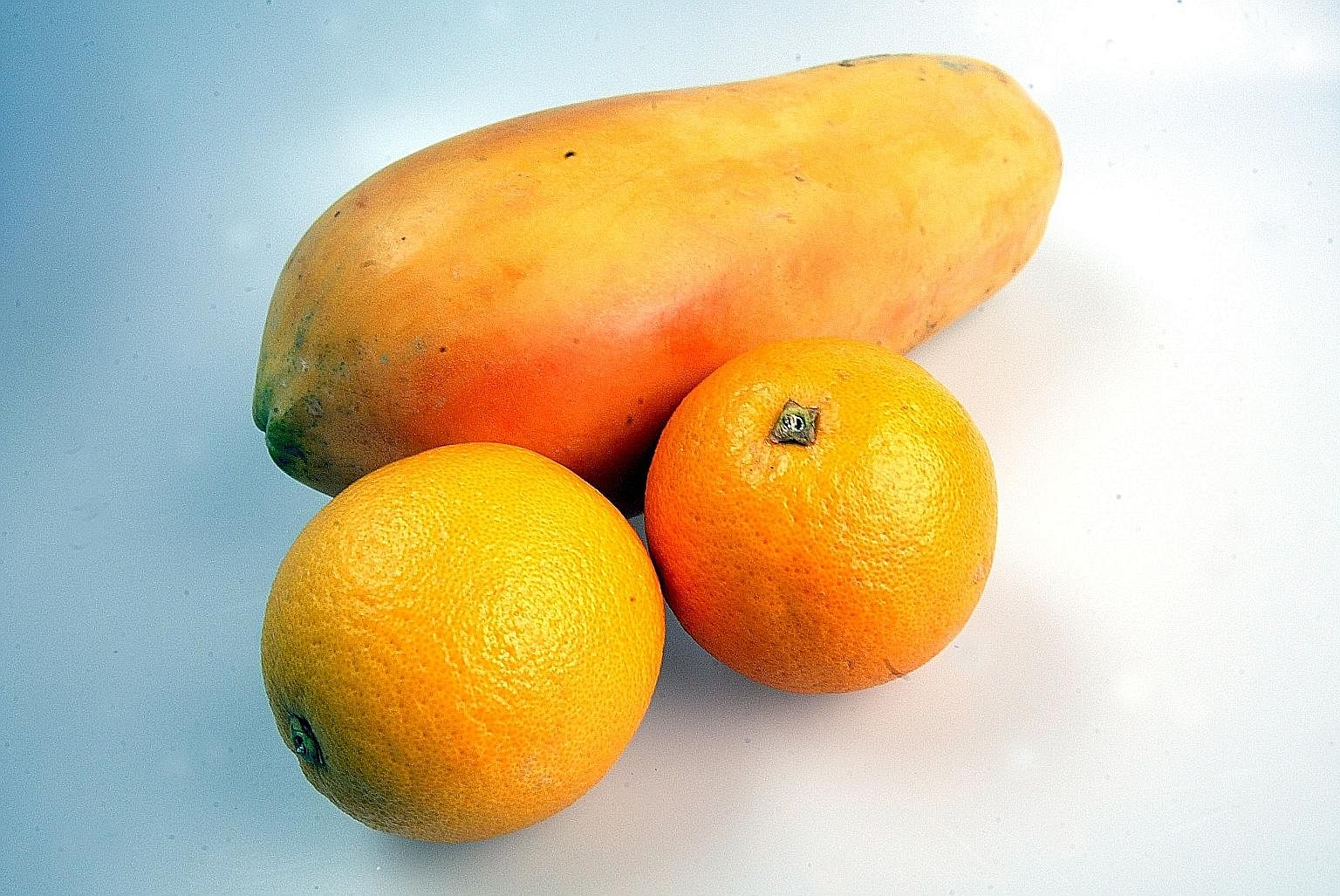

•Eating yellow-coloured fruits such as papayas, pumpkins and oranges may reduce the risk of lung cancer in smokers, probably due to the antioxidant beta-cryptoxanthin, which is in high concentration in these foods.

•Soy-based products may help reduce the risk of breast cancer and osteoporosis-related hip fracture in elderly women, probably due to the phytoestrogen in soy foods.

•Red meat may increase the risk of diabetes, probably due to heme-iron and other chemicals that affect the body's production of and sensitivity to insulin.

Findings from the SCHS benefit all Singaporeans, as many of the disease factors are not modified by genetic differences among the different major races. The future public health applications and policy implications of many of these findings were among the areas of discussion by various researchers and academia at the SCHS Symposium: A Legacy for the Future, organised by the NUS Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health, last week. Indeed, the study has great potential in contributing towards the scientific bases for public health programmes and policies for Singapore.

To continue providing such useful scientific evidence, we need to collect accurate medical information about our participants. Fortunately, SCHS has linkages with national disease registries to augment the information collected from study interviews.

Beyond the scientific aspects, a core area of cohort studies which has attracted intense attention is the protection of privacy. Every participant's trust must not be taken lightly, and privacy protection is a paramount priority. The SCHS operates on a robust framework which guards privacy and maintains data security, including regular reviews by an independent scientific ethics review board, removal of personal identifiers, and password protection to guard data access. For these reasons, the cohort study has not encountered any breaches of privacy to date.

That said, the true heroes of the SCHS are the 63,257 Singaporeans who generously shared information about their diet and lifestyle with the objective of helping to improve the well-being of fellow Singaporeans and future generations. It was a remarkable demonstration of the "kampung spirit" where each person wanted to support and help the community. The contributions of the SCHS participants provide valuable data that forms a continuing legacy for future research. As our participants age, we have begun studying the factors that contribute to healthy ageing. We also plan to recruit the children of our original participants to examine how inter-generational factors affect health and disease development in Singaporeans. This will be possible only if the next generation lends their support.

Following the success of SCHS, Singapore is ready to organise other cohorts linking interactions between genes and exposures to disease risk. We are optimistic that Singaporeans will continue to share their health information for such studies vital to research on disease prevention and promotion of health.

•Emeritus Professor Lee Hin Peng is professor at the Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health, National University of Singapore, and co-founding principal investigator of the Singapore Chinese Health Study (SCHS) and Professor Koh Woon Puay is professor at the Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health, National University of Singapore, and Duke-NUS Graduate Medical School. She is also the principal investigator of the SCHS.