Intellectually, we know that life is short and fragile. Yet, many of us live our lives and get through each day in a way that is quite inconsistent with this knowledge. Many things we do or think about - and how we feel about them - would be very different if we really appreciate that our time on earth is finite and could expire much sooner than expected without any warning.

Psychologists have found that people experience "mortality salience" when they encounter events that expose the fragility of life. This refers to the heightened awareness that our death is inevitable and unpredictable.

The impact is strongest when the events are highly personal. Some examples are a near-death experience, the sudden death of a family member or close friend, or when someone we identify closely with is incapacitated due to an accident or unexpected disease.

Mortality salience causes anxiety and stress. But it is not necessarily negative.

One positive impact is that it often leads you to ask questions about the meaning in your life. These "meaning in life" questions are about your own life and living. They are not about the profound "meaning of life" question that philosophy has been grappling with or religions have prescribed answers to.

When we wonder about meaning in our lives, we ask ourselves personal and practical questions about what we have been thinking, feeling and doing. It leads us to re-evaluate the way we live our lives.

MEANING MATTERS

Research has consistently found that people - regardless of socio-economic status, cultural worldviews and religious or secular beliefs - develop sustained and sustainable positive attitudes and experiences when they seek and find meaning in their lives.

Interestingly, the source of the meaning itself - be it family, friendship, religion, public service, volunteerism, skill mastery or personal accomplishments - is less important than the difference between simply having and not having a sense of meaning in life. Put in another way, having a sense of meaning in one's life is critical, and there are multiple pathways to gaining meaning.

Studies have shown that people who experience meaning in their lives are less likely to suffer from depression and anxiety. They are more resilient to adversity - they are better able to withstand negative events and more likely to recover from them. They are also happier and more satisfied with their lives.

In addition, they are more likely to have better physical health outcomes, and have a reduced risk of cardiovascular disease.

Having a personal sense of life's meaning has been found to predict longevity above and beyond other factors known to lower risk of mortality. It also predicted lower mortality across the lifespan, demonstrating a positive difference within similar age groups.

When people experience a life they find meaningful, it leads to beneficial outcomes not only for themselves but also the people around them and the communities they belong to.

Meaning in life predicts giving behaviours, including philanthropy and volunteerism, as well as pro-social behaviours such as sacrificing self-interest for the larger collective good.

These positive findings on meaning in life have been found to apply regardless of demographics such as sex, age, race, religion and nationality, and background status such as education level, occupation type, income level and retirement status.

Beyond the benefits for the individual, a sense of meaning in life has practical societal implications for adult development, healthcare and health promotion, positive ageing, team building, organisational development, community building, and, ultimately, developing a strong society and economy. So, governments should create enabling conditions to facilitate citizens to access opportunities and to feel empowered to find and make meaning in their lives.

LIVING MEANINGFULLY

At the individual level, how can we overcome obstacles to meaning-making and find meaning in our lives? Based on research in the behavioural sciences, I suggest the following five Cs.

- Complementarity. You find what you do meaningful when it matches what you want to do.

So, it is important to know your aptitude and develop your interests. Select choices and make decisions based on your interests, passion and abilities rather than convention and expectations of others.

When there is complementary fit between the demands of the task activities and your interests, passion and abilities, you are self-motivated to learn, and more likely to develop deep skills and competence in the domain. You will perform the tasks because you want to, not just because you have to.

Your interest also makes you more likely to innovate. The creative processes and outcomes associated with innovation provide a sense of task autonomy, task identity and task ownership that contributes to personal meaning in the activities.

Your task mastery and emotional involvement turn chores into challenges to be met by self-efficacy. Successful task accomplishment equals self-fulfilment, and not just mere work completion.

- Congruence. Another type of fit that affects your sense of life's meaning is the congruence between how you present yourself and who you really are.

Be your authentic self in your interaction with others at work or in social settings. This is about being honest to yourself, speaking up, and behaving in a manner that is consistent with who you are or really want to be, as opposed to what you think others like you to be.

This does not mean you should say completely everything that is in your mind. Authenticity is not extreme forthrightness or foolishness. To be selective in expressing your true thoughts and feelings is not dishonesty or lack of authenticity. It is simply practical wisdom, and common-sense discretion of good and acceptable social behaviours.

- Commitment. The experience of meaning in life is often preceded by high commitment. Commitment involves dedication and decision to do things in a sustained manner, directed at achieving a goal.

Meaning in life involves a sense of larger purpose in what you do for most or much of your time. The larger purpose tends to be at an abstract or general level such as having a happy family life, helping the poor or running a successful business.

For this purpose to impact your experience of meaning, you need to translate the general purpose into concrete goals. Setting goals and monitoring progress of goal pursuits are critical aspects of commitment. It is important to set your own goals that are specific, challenging and realistic, strive towards them, and review your progress to self-regulate decisions and actions where necessary.

- Contribution. When you help people or make a positive difference to society, you derive a sense of personal meaning from helping others live better lives. You also become more grateful for your own life conditions as you appreciate the situation of those who are less fortunate.

Volunteerism and philanthropy create meaning if they are motivated by genuine intent to benefit the recipient, but not if the act of giving is simply a means to achieve a self-interested goal such as fulfilling an organisation's key performance indicator or seeking personal glory.

To derive meaning, contribution need not be unpaid work. School teachers can experience personal meaning if they believe their work has benefited students in significant ways.

What matters is not whether the work is remunerated but whether the motivation is people-centric, whether there is a cause that one believes in, and whether the contribution has made a positive difference to the recipients.

- Community. One of the strongest predictors of a sense of meaning in life is quality social relationships that one has developed with the people within a larger group to which he or she is a member of. Such community bonds are particularly strong when members share similar interests or believe in a common cause.

The basis of the community may be religious, social or professional in nature. It is the quality interactions, the fellowship and camaraderie, and the personal attachments to the group that create the sense of group identity that gives significance and meaning to the activities associated with the community.

It is important to join a community which shares your interest or cause, and participate regularly in the naturalistic interactions within the community to develop and maintain quality relationships.

WHAT IT ALL MEANS

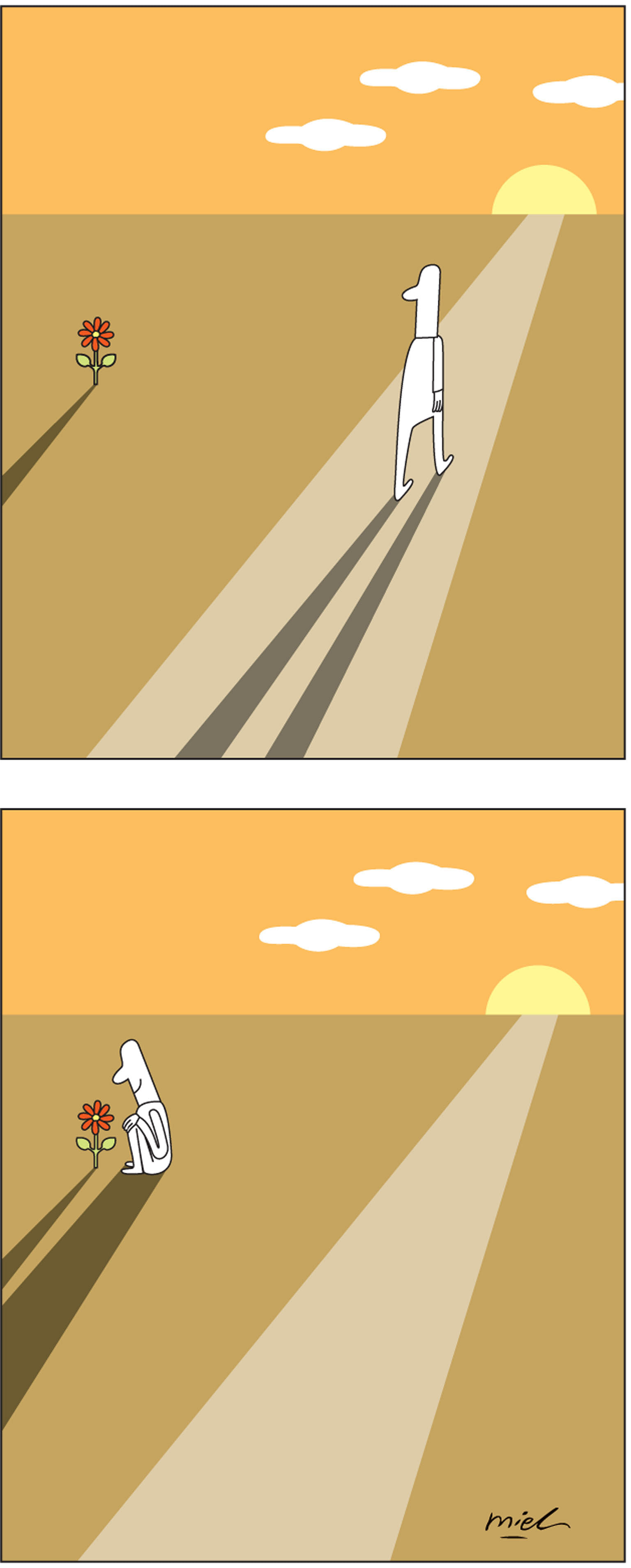

When we realise that life is short and fragile but we have a strong sense of our meaning in life, our fear of death and anxiety will be replaced with aspirations and inspirations that translate into positive attitudes and actions.

Of course, we will always have unpleasant obligations to fulfil and undesirable people to deal with. Sometimes, we need to say and do things that we do not enjoy but are necessary for good business, social and political reasons.

But responsibilities, norms and practical wisdom are not incompatible with seeking and living a meaningful life. They are not good excuses for investing all our time in thoughts, feelings and deeds that we strongly dislike and actually believe are a waste of our time.

There is clear scientific evidence of the benefits of developing a sense of meaning in life. At the more personal level, we can learn much from people who are living meaningful lives and the positive impact they have on themselves and others.

It makes good sense to make our lives meaningful, as experienced by ourselves and not defined by someone else.

A meaningful life is not just theoretically possible. It becomes a reality when we take practical steps to overcome obstacles to meaning-making and construct positive encounters, episodes and environments that create meaningful experiences for ourselves and others.

The writer is director of the Behavioural Sciences Institute, Lee Kuan Yew Fellow and Professor of Psychology at the Singapore Management University.