For most of history prior to the Industrial Revolution, Asia far outstripped Europe on indicators of development, while Europe was a peripheral upstart. Trade across vast distances between the Mediterranean and China along the Silk Roads long predated Europe's 15th-century voyages.

Far from being an undiscovered continent prior to European colonialism, Africa was for centuries an integral part of the Afroeurasian trading system. And well before Europe held any colonies at all, the Mongols presided over the largest territorial empire ever known.

These are just some of the facts of Asian history that have been lost over the past 500 years of colonialism and the Cold War, during which Asia became so fragmented that many societies have lost touch with the bonds that once tied them together. Due to the eurocentric nature of global history narratives, most Asians today are unfamiliar with the depth and contours of Asia's own history, especially its rich pre-colonial Silk Road eras of commerce, conflict and cultural patterns across the full sweep of terrain from Arabia to Japan.

Now more than ever, we need a common understanding of Asia's past to re-establish Asia's central role in global history: European empires became wealthy global powers because they subjugated Asia, and the United States' global influence today hinges on its relevance in Asia. Perhaps most important, Asians need to be reminded of what their collective historical achievements have been and consider what is possible in the future.

Here are some lessons from Asian history for Asia's future - and the world's.

CULTURE MATTERS

A panoramic arc of West, Central, South, East, and South-east Asian history going back thousands of years shows that Asia's linkages have been continuously propelled through commerce, conflict and culture. Turkic, Arab and Persian civilisations, as well as those of China, Japan and Korea, have been uninterruptedly accumulating and sharing knowledge for nearly 3,000 years.

The most basic example is language. Ancient Indian Sanskrit served as a model for written Thai, Tibetan and other regional languages, while in East Asia, the Chinese writing system came to Japan via Korea. The Arabic script became the basis of numerous oral traditions such as Farsi, Kurdish, Pashto and Urdu as they crystallised into written languages. The linkages across the Turkic, Persian and Indic worlds have resulted in thousands of modern cognates between Turkish, Farsi and Hindi.

Linguistic influence also flowed from West to East: Persian, not Chinese, was the lingua franca of the Silk Roads. The Tang Dynasty set up Persian schools to train its traders and agents to communicate with their counterparts in the western regions.

East Asian societies were also willing recipients of cultural ideas that arrived with commerce along the Silk Roads, especially Buddhism.

Commerce and conflict also enabled the intermingling of ethnicities and bloodlines through migratory settlement and marriage.

China, Japan and Korea have all had ethnically mixed dynasties. Chinese-ness is often perceived of as hewing to the Han ethnicity, but there is no one pure "Chinese" genetic stock, given the historical importance of the Mongol-Turkic Sui rulers, Mongol overlords, and Manchu dynasties.

The Chinese imperial administration, especially under the cosmopolitan Tang, employed countless bureaucrats and generals from other Asian cultures, with communities of Arabs, Turks, Persians and Mongols settled throughout the empire.

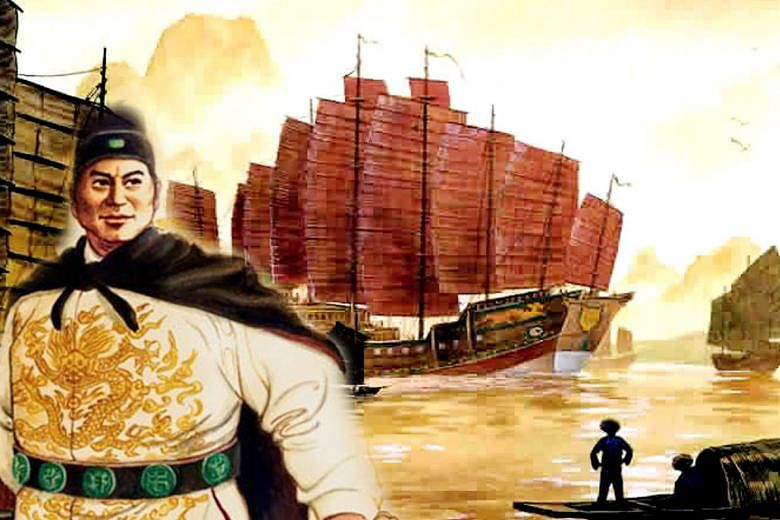

During the Ming Dynasty, the admiral Zheng He, a distant descendant of a Song-era Muslim Persian migrant, led the Ming's famous maritime voyages as far as Africa.

The later Qing military was dominated not by Han but by Mongols and Manchus. Similarly, Arab, Persian and Turkic fusion made the Abbasid Caliphate an impressive intellectual, cultural and military power, one capable of penetrating India and establishing the Delhi Sultanate. Mongol DNA is significant in the lineage of numerous Asian peoples. Asian identity has long been more syncretic than ethnic.

RELIGIOUS DIVERSITY

Religious diversity has also been a pillar of Asian civilisations' stability. Vedic Brahmanism, Zoroastrianism, Shintoism and Buddhism were established faiths centuries before the advent of Christianity, which along with Islam emerged from West Asia.

-

Parag Khanna's new book out now

-

This excerpt is adapted from Dr Parag Khanna's new book, The Future Is Asian (Simon & Schuster, 2019), now out in bookstores.He will launch the book at Kinokuniya (Takashimaya) on Saturday at 2pm, and at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy on Jan 16 at 5.30pm.

It retails for $29.95 at Kinokuniya in stores and online.

These religions often coexisted in harmony as they adapted to local circumstances. Buddhism is inseparable from the religious and cultural psyche of East Asia, where Confucianism was also a common bond that provided a means through which elites could understand one another even when their relations were adversarial. In Tang China, it was declared that "Buddhism is the sun, Taoism is the moon, and Confucianism the five planets".

The early caliphates, Mongols, Mughals and Ottomans are all examples of Asian empires whose inclusive religious tolerance aided their expansion by reducing fear among their new subjects. Though discriminatory taxes were levied on minorities in many societies, in most cases they did not amount to persecution. The third Mughal emperor, Akbar, decreed that any Hindus converted to Islam could return to Hinduism without penalty.

It is almost impossible to explain the historical role of one faith without the others. In South and South-east Asia, syncretism between Hinduism and Buddhism was most common, with an Indianised Mahayana Buddhist culture emerging in many of the early South-east Asian kingdoms.

The Khmer Empire that dominated much of peninsular South-east Asia from the ninth to the 13th centuries was a Mahayana Buddhist Hindu dominion. The resplendent Angkor Wat in Cambodia began as a Hindu temple in honour of the Lord Vishnu but by the 12th century had become a Buddhist temple. Even the nihilistic Pol Pot dared not desecrate it. Today, it is the only building on a national flag. The Srivijaya Empire of Sumatra was also a Hindu-Buddhist civilisation.

On top of this layering, South and South-east Asian culture cannot be explained without Islam, brought by Arab traders along maritime networks and its coexistence for more than 1,000 years with Hinduism, Buddhism and Christianity.

Though Islam has Arab origins, Muslim populations are larger the farther east one travels through Pakistan and India towards Indonesia, the largest Muslim-populated country in the world. Today, the vast majority of the world's 1.6 billion Muslims live in Asia (and 300 million in Africa).

For Asians, Islam cannot be viewed as foreign and adversarial. Unlike in the 14th century, West Asia today looks up to East Asia's success - and is learning lessons from it on how to manage political Islam flow from East to West.

One might suggest that the fundamental differences among Asia's dominant religions are the reason they have been able to coexist in stability: They are so dissimilar yet each is so numerically robust that the conquest of one by the other is both spiritually unthinkable and logistically impossible. Asians have no choice but to live and let live.

ASIA AND THE WEST

In addition to Asia's history of diversity, there are also lessons to be learnt from its rich history of precolonial connectivity. Asia's commercial and cosmopolitan cities formed a network of hubs spanning numerous multi-ethnic and multilingual empires.

In the 10th century, the Tang Dynasty's imperial library had 80,000 volumes, while the largest library in northern Europe at the time, in the monastery of St Gall in Switzerland, had only 800. European explorers themselves remarked at how India's and China's cities were larger than London and Paris. Over many centuries, cities from Baghdad to Delhi to Chang'an served to exchange and revitalise knowledge from near and far.

In key areas of science and technology - irrigation and bridge building, clock making and gunsmithing, papermaking and navigation - Asia was the inventor and Europe acquired the knowledge secondhand. Paper entered the Islamic domain after the Arab victory over the Tang in AD 751, after which imprisoned Chinese papermakers transmitted their skills to Muslim craftsmen in Baghdad and Damascus, then Egypt and Morocco, and eventually Spain and Italy.

COMPETITION FOR TERRITORIAL AND TRADE ROUTES

In each phase of Asian history, geopolitical competition for territory and trade routes expanded the reach and intensity of the whole system. Already in the 13th century, the Mongols managed to link much of the world known at the time. For numerous Song Chinese and South-east Asian maritime entrepots, external trade was crucial to the survival of local economies. The Chola, Srivijaya, and Ming all jockeyed for control over Indian Ocean trade routes long before the arrival of European merchants.

For most of history, then, Asians have been far more aroused by one another's imperial ambitions, especially the expansionist Arabs, Mongols, Timurids, Qing and other powers. Until the 16th century, the West remained on the sidelines of the thriving Asian system, and before 1800, trade flows among Chinese, Indians, Japanese, Siamese, Javanese and Arabs were still much greater than those within Europe.

Only in recent centuries have Western societies actually been a geopolitical concern in Asia. Yet even as European empires persisted into the 20th century, it was Japan that besieged the Pacific Rim from Vladivostok to Darwin.

Today, despite the US military presence in East Asia, China's ambitions consume the region's geopolitical forecasting far more than do those of the United States.

Asians should view Europeans' arrival and ascent in their terrain far more as the product of luck than ingenuity. Had it not been for the Ottomans' sacking of Constantinople and threatening of Europe from the east, Europeans would have been less motivated to explore westward in search of East Asia (landing in America instead).

And had the Ming Dynasty not chosen to retreat inward in the late 15th century, it is unlikely that Europe's East India companies would ever have established advantageous positions against the Ming fleets.

Europe thus gained the most from Asia's pre-modern globalisation, acquiring knowledge of weaponry and navigation from Asia that it used on trade routes opened by India and China. When Asians look at the colonial period, therefore, they see an era of complacency, not inferiority. Their collective lesson is that when they are in conflict with one another, outside powers will exploit them.

Colonialism's mix of capitalism, technology and manpower did, however, give areas of Asia a head start into the modern world. Hong Kong and Singapore became leading financial centres, drawing Asian talent from near and far, Gulf monarchies harnessed oil deposits through joint ventures with Western companies, and railways helped forge a more united Indian subcontinent.

When it comes to migration, colonialism's lasting legacy has been to make Asia even more Asian. European empires from the Portuguese to the British moved Malay and Indian merchants and slaves by the millions across the greater Indian Ocean realm. Steamship ferry services across the Bay of Bengal and South China Sea galvanised regional migration. At the same time, the pan-Asian anti-colonial movements of the 19th and 20th centuries inspired Asians to rediscover a common spatial and political understanding of Asia.

Though colonialism was a humiliating experience, it nonetheless provided a common layer on which Asians are now building a post-Western future. Asians are realising that they have much more to learn from one another than from the West. Ultimately, perhaps the greatest Western legacy will have been to accelerate the self-actualisation of Asia.

ASIA AFTER THE WEST: USES AND ABUSES OF WESTERN EXPERIENCE

Given Asia's rich historical record of intercivilisational interactions, it is odd when Western scholars make analogies to European history to explain Asian states' behaviour. Is Germany's 19th-century rise a better way to interpret China's ambitions today than a combination of Tang and Ming history?

Should the United States really hold up India as a continental counterbalance to China when India's golden era was under the seafaring Chola Dynasty, which ruled the waves?

Can Iran be confined to its present national boundaries when for much of history, Persian empires reached the Mediterranean Sea?

Since we are talking about China, India and Iran, surely it makes more sense to assume that Chinese, Indians and Iranians think and act more through analogies with their own histories than with the West's.

Unlike in the West, where religious conflict has been a defining attribute of the system's formation, Asians have long tolerated one another's belief systems, demonstrating over many centuries a capacity for interethnic and religious coexistence at the international level.

Today, despite religious differences, India's ties with the Gulf Arabs, Iran and Indonesia are getting stronger with each passing year of military and commercial cooperation. Confucian and Muslim societies at opposite ends of Asia have little to fear from each other. They form not a geopolitical axis but a restoration of the Silk Road commercial axis.

A similar logic applies in the geographic domain. Whereas European history features consistent fear of a singular regional hegemon, Asia's geography makes it inherently multipolar.

Natural barriers absorb friction. Vast distances, high mountains, and other natural boundaries such as rivers protect Asians from excessive encroachment on one another.

Taken together, the combination of geography, ethnicity and culture has significantly contributed to Asia's recent wars among neighbouring powers - China and India, China and Vietnam, India and Pakistan, Iran and Iraq - ending in stalemate.

And whereas European history teaches that wars occur when there is a convergence in power among rivals, in Asia, wars occur when there is a perception of significant advantage over rivals. Thus the more powerful China's neighbours such as India, Japan and Russia grow, the less likely conflict among them becomes.

To the extent that Western scholarship uses Asian analogies to divine the future, it often chooses the wrong ones. The most common is to suggest that Asia's future will resemble China's tributary system, which operated primarily from the late 16th to mid-19th centuries, during the Ming and Qing dynasties.

But the geographic scope of the tributary model never reached meaningfully beyond East Asia. Furthermore, the tributary system revolved around trade; China exercised minimal political or military hegemony.

China has never been an indestructible superpower presiding over all of Asia like a colossus. Western theoretical abstractions paint a false choice for Asia between hegemony and anarchy, whereas the reality is much more rooted in Asia's multicivilisational, multipolar past.

There are, however, Western colonial influences that have been baked into the fabric of the region, perhaps only slowly (if at all) to be undone: state sovereignty over fluid borders, religious and ethnic national divisions over multi-ethnic identities, consumerism and materialism over clan and kinship.

There are exceptions to these shifts, but each has shaped Asia to a considerable degree. Asians must now decide to what extent Western legacies will be Asianised and what elements of Asian history will be recovered.

The most pertinent questions facing Asia are about neither ideology nor hegemony, but rather about how to demarcate and share territory.

Asia's main tensions are not between civilisations but between nations. Asian civilisations have maintained deep patterns of mutual respect and learning for millennia, while post-World War II sovereignty and nationalism have left a legacy of boundary disputes that still need to be resolved for Asia to fully return to its pre-colonial fluidity.

The zero-sum nature of sovereignty requires clarity as to who owns what territory or water. Modern international law has imposed a sense of finality and permanence. The desire to ratify territorial claims has sharpened dormant tensions. Kashmir and Palestine are just two examples of how Asia today remains littered with conflicts that combine the legacies of European colonialism, exigencies of state sovereignty, and local ethnolinguistic factions.

Even Asia's foreign-manufactured security challenges have become regional ones. Many Asians, especially Arabs and Indians, continue to blame the West for their unresolved boundaries and sectarian politics, but this is of little value in conflict resolution. Asians, not Westerners, will suffer the most from fighting over terrain they have long shared.

The principal lesson from Asia's geopolitical history is that no one power's dominance has lasted for very long before meeting sufficient resistance - internally, from neighbours, or both - to dash its hopes of eternal hegemony.

Whether the Mongols, Ming China, or imperial Japan, Asia's disparate societies have proved too diffuse and impenetrable to be fully absorbed by others.

Over the millennia, Turkic, Persian, Arab, Indian and Russian empires have also sought to establish hierarchies in Asia with themselves as the core power.

Asia will always be a region of distinct and autonomous civilisations, a number of which, including China, India and Iran, have an ingrained sense of historical centrality and exceptionalism. As a result, the most any power has achieved is to be a thriving subregional anchor in a multipolar Asia - very much the scenario unfolding today.