-

Getting there

-

Great Rail Journeys (www.greatrail.com) has an 11-day tour of the Arctic Circle costing £2,295 (S$4,100) a person. KLM offers daily flights from Singapore to the Norwegian capital of Oslo - where the journey begins - via Amsterdam.

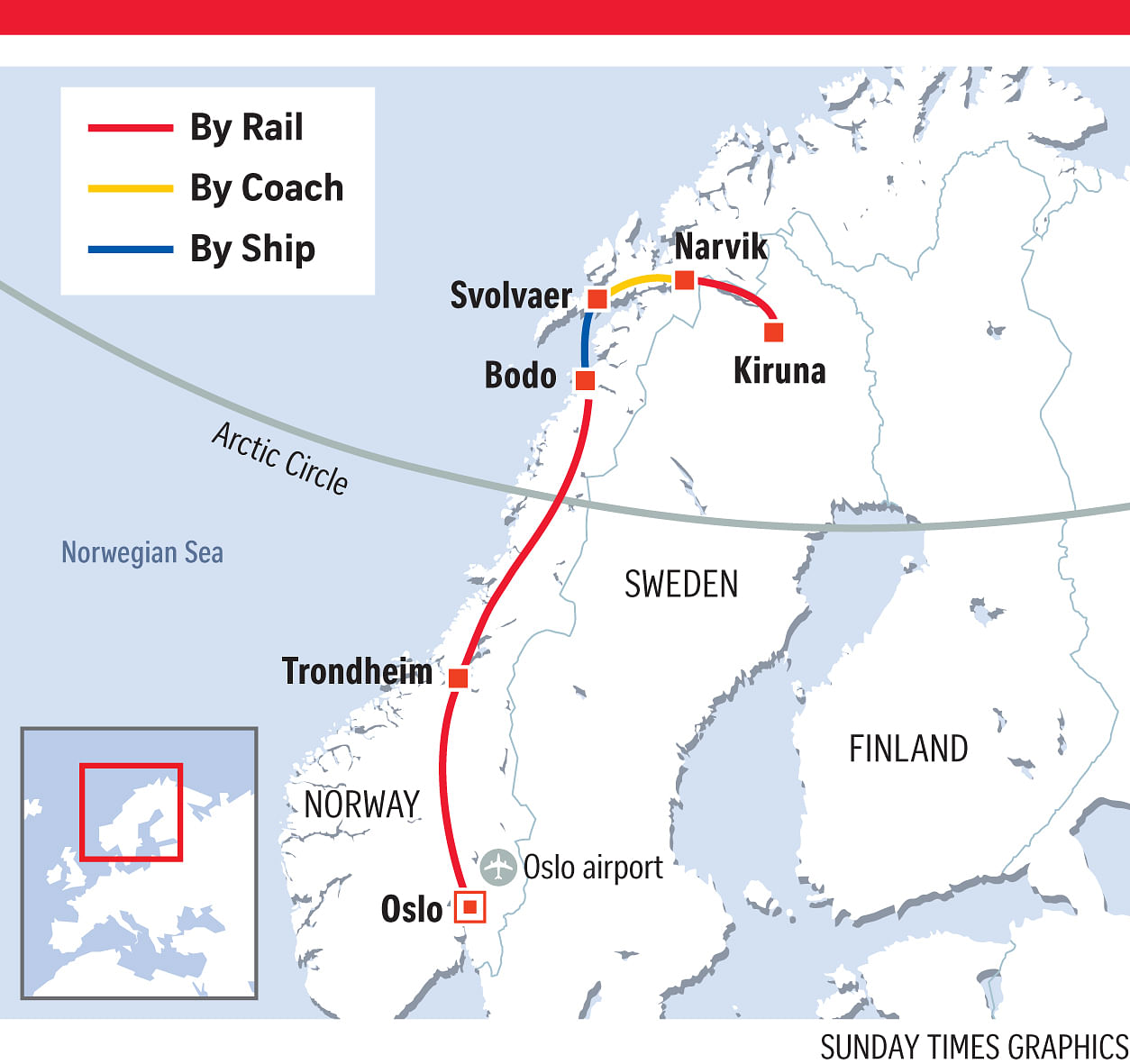

After an overnight stay in Oslo, the tour continues by rail up the Norwegian coast to beyond the Arctic Circle, with stays in Trondheim and Bodo.

Continue the tour by Hurtigruten ship to the remote Lofoten Islands, with opportunities to see the Northern Lights.

Returning overland to Narvik, the tour travels along the world's northern-most rail line to Kiruna, in Swedish Lapland, culminating in a visit to the Ice Hotel and a close encounter with Sami culture.

Journey by train and ship to the Arctic Circle

Journey through the Arctic Circle by train, ship and dog-sled and take in mountains, quaint towns, reindeer and the Northern Lights

As our train trundles through the ice and snow, I find myself thinking that the constants of Norway are hot and strong coffee and dramatic scenery.

I am travelling up the wild western edge of Norway to far above the Arctic Circle, to explore the culture and landscape of Lapland by train and ship over 11 days, starting in Oslo and stopping overnight in several Arctic towns. We may even enjoy the contorted colours of the Northern Lights.

Our north-bound train with Great Rail Journeys (www.greatrail.com), based in the United Kingdom, parallels a series of broad rivers, each resembling a Braque painting, with triangular sections of ice piled upon one another, as the surface of the water thaws into flow then freezes once again.

Closer to shore, pathways have been brushed through the fresh snow which lies atop the ice. This temporary trail system leads between small fishing shacks. A man twirls a dowel into the ice to create a passage in which to cast his lure.

The rivers all enter the mountains at some point, fed by waterfalls whose contorted shapes are reminiscent of the Munch painting I had seen the previous day in Oslo's National Museum (www.nasjonalmuseet.no/en). If this landscape has a theme, it would be the movement of water arrested.

I suppose I can expand this to be movement itself arrested, in the slow-moving trains, oddly shaped rocks that appear to be suspended mid-fall, and the deliberation of human locomotion when traversing the unpredictable element of ice.

We ourselves experience that in Trondheim later, when we disembark the train and make our way gingerly along its icy streets.

Nidaros Cathedral (www.nidarosdomen.no/en), Scandinavia's largest mediaeval building, holds court massively at the centre of town. It has been built upon the grave of the Viking king Saint Olav, who replaced the old pagan religions with Christianity.

There are a great number of old tombstones found within the cathedral, as well as in the adjacent bank and library, these modern structures having been respectfully built around the exposed ruins of ancient churches.

Just across the river is the old part of town, its multicoloured wooden homes queuing politely beneath Kristiansten Fort. This is the Scandinavia of our imagination under a winter light perpetually soft and ideal for photography.

My Singaporean travel companion and I also wander to Trondheim's shops and picturesque old buildings. The variety of locally made goods for sale here is a testament to Norway's healthy economy and apparent self-sufficiency.

We eventually stop for a light dinner at the Ravnkloa Fish Market, where I find the perfect complement to a salmon sandwich in a bottle of ale brewed at Trondheim's own microbrewery.

We cross the Arctic Circle midafternoon the following day. The first hint of its approach comes in the form of an ice-covered train heading south. Until then, we had seen far more ice than snow on our trip in late February, early March - during a winter made warm due to El Nino.

We tend to think of the Arctic as a dry, flat, desolate place, but the landscape before me is certainly three-dimensional, beneath mountains that look like filed teeth and through long narrow valleys, their craggy walls scarred by glaciers. These walls have birthed sections of shale that I see stacked in railyards to be shipped overseas for the homes and gardens of the south.

Our group celebrates crossing the Arctic Circle with a champagne toast, as outside the window a large stone cairn drifts by.

Growing up with tales of the Arctic, you come to believe that it is uninhabitable to nearly all. But now and again we pass the occasional lone farmhouse, in complete isolation, yet perhaps finding some comfort in the human connection with the rail line.

I love these little moments of surprise. At its best, travel can be seen as a puzzle, each successive journey enabling a familiarity with the contours of a new piece, the shape of the world eventually to be formed by the traveller himself.

It is dusk as we arrive at our hotel in Bodo. I step back out onto the icy streets, trying to find a replacement for the scarf I accidentally left in my hotel that morning. It is then that I get my first glimpse of the Northern Lights, a dull orange glow that hangs over the harbour and the hills beyond. They last only a short while and by the time we take a few photos, they are gone.

They will appear again the next night, this time in blue, as we disembark our ship in Svolvaer.

Part cruise ship, part ferry, the Hurtigruten is the classic Norway experience and many travellers hop from port to port, 35 in all, as the ship traces Norway's rough fjord-lined coast over several days.

I spend part of the journey in the hot tub on deck, forgetting the cold as I marvel at the landscape of oddly shaped mountains that the glaciers have left behind.

The Arctic is a windy place, the air in near constant movement over these still, grey waters. As the gusts dance across their surfaces, they go greyer still. It is a quick, brisk walk from tub to table, where I warm myself with a hardy reindeer steak, a staple dish in much of Scandinavia.

Looking ashore, I notice the candlelight that fills nearly every window of the houses there, as if mimicking the soft light in the winter sky.

The following day, we set out on a tour of the Trollfjord, zipping along the icy waters in an open Zodiac boat (www.lofoten-explorer.no/en).

From the sea, Svolvaer's relationship with the water quickly becomes apparent. This fishing town is built atop a series of rock islets interconnected by wooden piers.

On the way to the fjord, we pass beneath swirling sea eagles, each with a wingspan the width of our Zodiac. It is a wonderful ride, beneath jagged snow-covered peaks and past the odd lone cabin, now closed-up for the season.

Within the fjord itself, we are told it is wide and deep enough for the large Hurtigruten ship to make a U-turn. Above the waterline, I spy a group of cross-country skiers gliding slowly along, on a multi-day excursion.

We make an excursion of our own that evening, dinner with a photographer famed for his shots of the Northern Lights, who gives us hints on how best to capture them.

Midway through dinner, I remember the zen parable of the danger of mistaking the moon for the finger that points its way and excuse myself to go outside and look for the Aurora.

Sadly, all is clouded over. It must be minus 20 deg C, but I stand without jacket in the cold, trying to catch snowflakes on my tongue.

I later thaw with a cocktail at the Ice Bar, whose interior temperature hardly differs from that without, sipping from a glass that is made of ice.

An overnight at Narvik breaks the journey from the Lofoten peninsula to the Swedish border. Here, we board a train and head south-east.

The first hour is spent climbing above a fjord, the waters from this height showing a brilliant blue. The town of Katterat at the end of the fjord marks the Swedish border, where the train discharges a handful of Nordic skiers, one of whom is struggling to hold the leash of a very enthusiastic dog.

I wish I could say I was as enthusiastic about our final destination. Kiruna is a modern city and its look reflects that. Perfunctory twostorey structures of simple brick are laid out at random angles along the compact maze of streets. The town was built in 1900 as a settlement for the still-working iron ore mines visible from anywhere in town.

Aside from the Kiruna Church (voted the most beautiful building in Sweden), there is little of interest, barring perhaps a wonderful meal at SPiS Mat&Dryck (www.spiskiruna.se), whose menu is as creative as the wine list is broad. There seems nothing incongruous about a dinner in Lapland, with Argentinian Malbec in the glass and Isaac Hayes coming through the speakers.

Thus fortified, we plan a series of excursions for the following day. We are picked up by Tommy Petersson, the owner of Laxforsen Sleddog, for a dog-sled ride across the frozen surface of a lake.

He is a friendly and knowledgeable man who truly loves and cares for his dogs. Once in harness, they leap and spring in the air as if as excited as we are.

We move briskly through the snow-covered forest, the only real sounds being the soft commands coming from Mr Petersson. I am amazed that the dogs can hear, but he explains that yelling is unnecessary and would destroy the bliss of near silence.

After an hour or so, we drink around a bonfire. Here, Mr Petersson explains that smaller operations like his have the healthiest dogs, since personal care can be spent with each one.

As I ride behind the dozen dogs on our return journey, I gaze out across the rolling terrain and think of my great grandfather, who emigrated to the United States from Sweden, a young man who had paid for his fare by working for a number of years as a guard at a logging camp, protecting the workers from wolves.

Further down the Torne River is the world-famous Ice Hotel. Originally inspired by Japan's Sapporo Snow Festival, artists from around the world gather to rebuild the hotel each winter, each trying to outdo one another in creating the most clever or bizarre designs. Come spring, the entire structure will melt and return to the river.

Guests can opt to sleep beneath reindeer hides in one of these creations, or can choose from one of the heated permanent rooms next door. As we already have a comfortable hotel in town, we merely wander around for a look, before having a bountiful lunch in an old 19th-century house on the grounds.

As night begins to fall, our group meets with a guide from the local Sami tribe. More colloquially known as Laplanders, the Sami have been living and herding in this area for 6,000 years.

Our guide leads us to a reindeer pen, where we feed these impressive animals with their grand antlers. Reindeer play a large part both in the folk tales he shares with us that evening and in the meal itself, in the form of cranberry-covered steaks grilled to a tenderness surprising in a game animal.

There are few things finer than a meal had with friends in a quiet corner of the world, in the company of a people whose way of life seems far from the troubles of the more populated nations to the south.

Leaving the others to continue their meal, I step outside to find a brief moment to myself.

The northern lights are hidden somewhere above, but I find this appropriate as their dazzling electrical dance would only distract anyway. I am happy instead to have the dark, and the solitude, and the sound of my breath echoing off the snow.

•Edward J. Taylor is an American freelance writer based in Kyoto.

Join ST's Telegram channel and get the latest breaking news delivered to you.

A version of this article appeared in the print edition of The Sunday Times on September 04, 2016, with the headline Journey by train and ship to the Arctic Circle. Subscribe