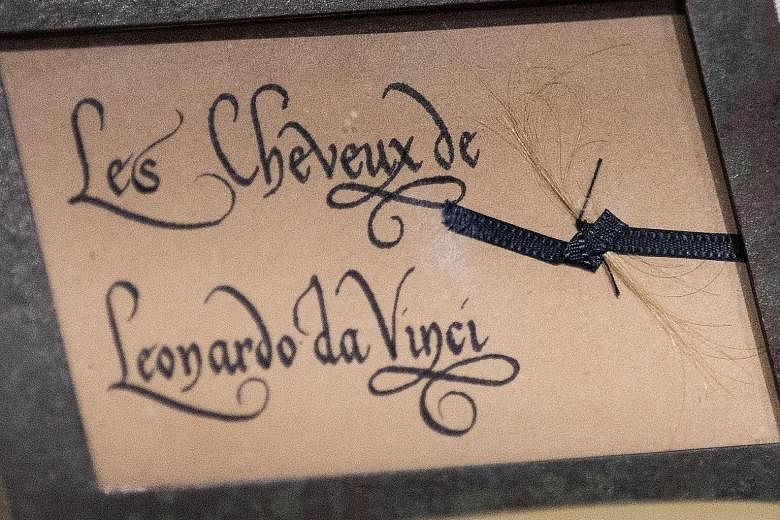

VINCI (Italy) • An Italian museum says it plans to carry out DNA tests on a lock of hair it believes might have belonged to Renaissance artist Leonardo da Vinci, who died 500 years ago this month.

However, some experts have thrown doubt on the exercise, saying the hair almost certainly did not belong to the Italian master, while credible DNA testing may prove impossible.

Da Vinci died in May 1519 and was buried at the Chateau d'Ambroise near the French city of Tours. The castle was badly damaged following the French Revolution of 1789 and many graves were destroyed, including that of da Vinci's.

Mr Alessandro Vezzosi, director of the Ideal Leonardo da Vinci museum in Vinci, the artist's hometown in Tuscany, said the strand of hair was collected from the site in 1863 by a man tasked by a royal commission to try and locate da Vinci's remains.

"In 1925, an American collector bought this relic in Paris... Later, before dying aged 95, he sold it to another American collector, who contacted us," Mr Vezzosi said.

He said the museum planned to extract DNA from the sample and compare it with the DNA from a group of descendants whom the museum says it identified in 2016, using genealogical records.

The testing should also be able to prove if the remains identified in France in 1863 really belonged to da Vinci.

"What is important is not to take for granted a result before the scientific testing is completed," said Mr Vezzosi.

But some experts are already pouring cold water on the whole exercise.

"It is highly improbable that this lock (of hair), which was presented like a (religious) relic, would be in any way related to Leonardo da Vinci," said Mr Eike Schmidt, director of the prestigious Uffizi Gallery in nearby Florence.

Finding a DNA link with living descendants will prove an added complication, with tracing possible only via the mother and an unbroken female line, or the father and an unbroken male line. The identity of da Vinci's mother is unknown.

The artist never married and left no direct heirs, so the DNA will be checked against that of the descendants whom Mr Vezzosi said had been found by following the family trees of other children born to da Vinci's father.

The chance of re-creating an unbroken male line over 500 years is extremely unlikely.

Meanwhile, a new study said da Vinci may have suffered traumatic nerve damage that left him with a "claw hand", impairing his ability to paint later in life.

The damage could have been the result of a fainting episode, according to Italian research published last Friday in the British Royal Society Of Medicine journal.

Reconstructive surgeon David Lazzeri and neurologist Carlo Rossi said the handicap prevented the artist from holding his palette in his right hand, though he continued to draw with his left.

Many researchers have assumed that the palsy of his right hand stemmed from a stroke or Dupuytren's contracture, a condition that causes fingers to become permanently bent.

The two scientists reached their finding by studying a chalk drawing of da Vinci attributed to 16th-century Lombard artist Giovanni Ambrogio Figino.

The picture shows the Italian polymath with his right hand emerging from his clothing, as if he were wearing a sling, with the fingers contracted.

"Rather than depicting the typical clenched hand seen in post-stroke muscular spasticity, the picture suggests an alternative diagnosis, such as ulnar palsy, commonly known as claw hand," Dr Lazzeri said in the report.

For the Italian experts, da Vinci's physical weakness was not accompanied by any cognitive decline.

But according to Dr Lazzeri, it may explain "why he left numerous paintings incomplete", even including his most famous, the Mona Lisa, during the last five years of his career as a painter, "while he continued teaching and drawing".

According to another study carried out by Florence Museum researchers and published last month, da Vinci was completely ambidextrous - capable of writing, drawing and painting as well with his left hand as his right.

The findings were based on analysis of his earliest work.

REUTERS, AGENCE FRANCE-PRESSE