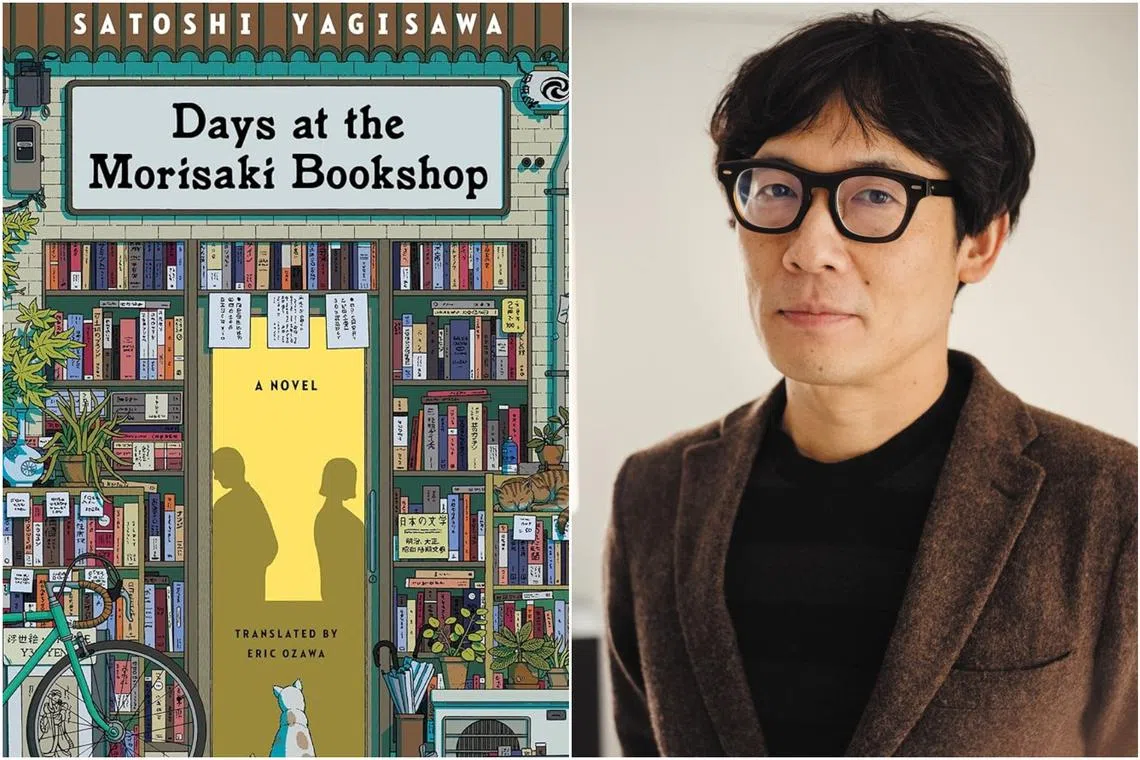

Book review: Bestseller Days At The Morisaki Bookshop twee tale of finding peace at a second-hand bookstore

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Days At The Morisaki Bookshop was Japanese author Satoshi Yagasawa’s debut novel in 2010.

PHOTOS: PANSING, SATOSHI YAGISAWA

Follow topic:

Days At The Morisaki Bookshop

By Satoshi Yagisawa, translated by Eric Ozawa amzn.to/3MAXr5Q

Fiction/Manilla Press/Paperback/147 pages/$21.91/Amazon SG (

3 stars

A colossus on international bestseller lists, this novella about the mind-expanding effect a Tokyo bookshop has on an ordinary office lady is unfortunately twee to the point of semi-blandness and lacks ambition.

It is part of a wave of feel-good, easily digestible books now emerging from East Asia, seemingly written to cater to that most indulgent instinct of book lovers – their love for the transformative space of the bookshop.

First published in Japanese in 2010, it was author Satoshi Yagisawa’s debut and won the Chiyoda Literature Prize.

It has been newly translated by Eric Ozawa for the English market, perhaps with a greater marketability now, given the nostalgia for independent spaces and more generally as an escape from the world.

Days At The Morisaki Bookshop is written in that by now all-too-familiar “Japanese voice” – detached introspection, stunted connection with others and an overwhelming quiet as if the world has been muffled with a duvet or submerged underwater.

It is essentially a two-parter. The first begins with the deliciously absurd premise that Takako, who thinks she has been dating her colleague, is suddenly confronted one day with him announcing his marriage to another woman.

Gaslit and heartbroken, she accepts her oddball, estranged Uncle Satoru’s invitation to live with him in his second-hand bookstore in Tokyo’s Jimbocho district, the largest concentration of second-hand bookshops in the world. (For the most bookstores per person, look instead to Buenos Aires, Argentina.)

There, she slowly gains perspective and settles into the pedestrian rhythms of reading, drinking at coffee shops and reconnecting with her uncle, gradually regaining the strength to leave.

The second, and more interesting section, introduces the more complex character of Aunt Momoko, Uncle Satoru’s hippie wife who had years earlier upped and left him with no explanation, but who has now returned.

At her uncle’s request, Takako returns to the bookshop to figure out why, and a tragedy is quietly revealed.

The relationship between Takako and Uncle Satoru is then consigned to the backdrop as Aunt Momoko launches her charm offensive, taking Takako on a trip to the mountains.

Both parts of Yagisawa’s tale are beautifully but procedurally sketched – romanticism but without the sturm und drang.

Readers do not know much about Takako’s life outside these two stretches of time spent in Jimbocho, and the implication is that they need not concern themselves with these.

The time spent at Morisaki Bookshop is as edifying as it is inconsequential. Much like reading this book, the experience is self-contained, suffusing readers with an escapist peace that they can then store for their more hectic “real lives”, without the experience necessarily meaning anything in itself.

The little moments that are supposed to create incisive meaning, upon closer examination, more resemble semi-meaningful glances and vaguely suggestive dialogue.

Takako does transform from a person who would not give books a second glance to an avid reader, but this feels trite and self-congratulatory, especially since it is written for people who likely love reading.

There is, however, a pleasingly cinematic finale, written as a second-hand account that one imagines could be played out perfectly on screen in silence.

And perhaps with actors filling in the blank spaces, the reticence in this book could be better coloured in with micro-expression and movement.

As text, this is too mild to be satisfying, and is perhaps more suited as a good stress-relieving or commuting read.

If you like this, read: The Midnight Library by Matt Haig (Canongate Books, 2021, $18, Amazon SG, go to amzn.to/3StAchG

This article contains affiliate links. If you buy through these links, we may earn a small commission.