US oil prices plunge below zero for first time in history

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

NEW YORK (BLOOMBERG, REUTERS) - Oil continued its unprecedented sell-off on Tuesday (April 21), the day after prices fell below zero for the first time in history.

Demand for oil has crumbled due to the coronavirus crisis, thrusting markets into a parallel universe where traders were willing to pay US$40 a barrel just to get somebody to take crude off their hands.

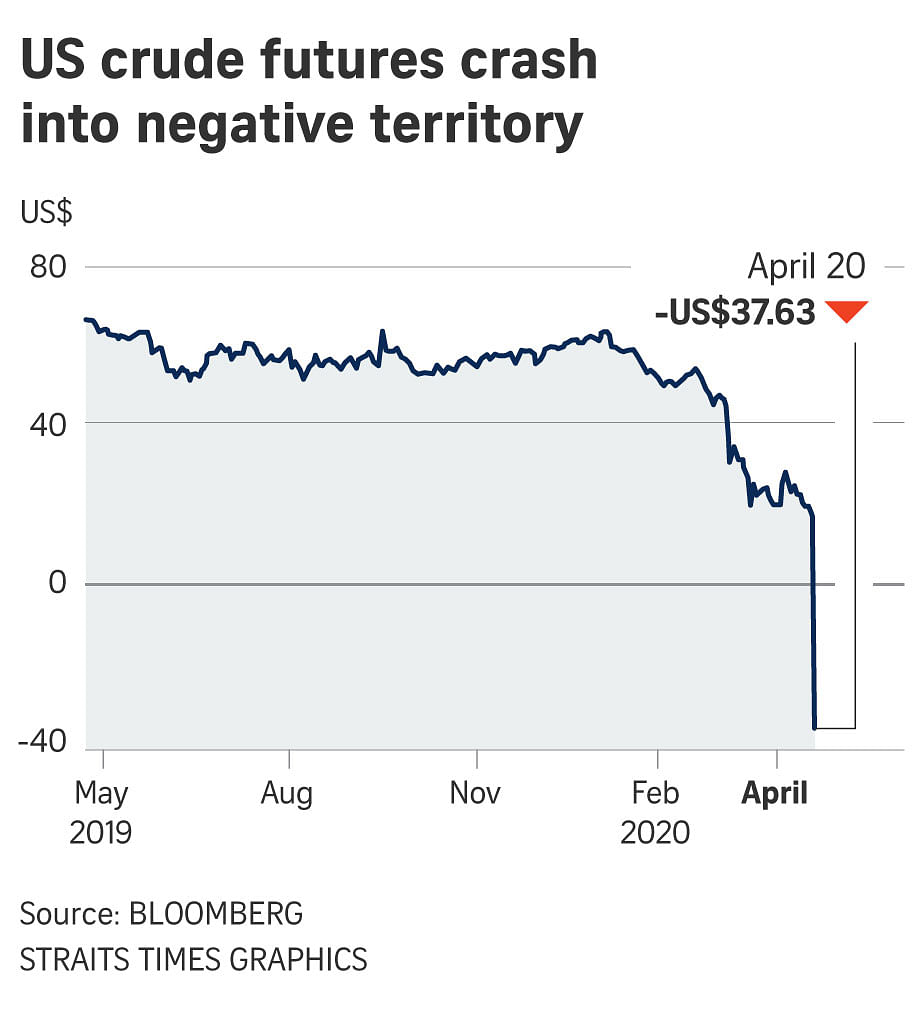

West Texas Intermediate (WTI) futures have been the benchmark for America's oil industry for decades, seeing the market through booms, busts, wars and financial crises, but no single event holds a candle to this. By the end of trading on Monday, the WTI contract for delivery in May had crashed 300 per cent from US$17.85 a barrel to minus US$37.63.

"Today was a devastating day for the global oil industry," said Mr Doug King, a hedge fund investor who co-founded the Merchant Commodity Fund. "US storage is full or committed and some unfortunate market participants were carried out."

In one way, it was just an extreme glitch as traders prepared for the expiry of the May contract. On Tuesday, the May contract still traded below zero - minus US$3.99 at 1200 GMT - after briefly clawing its way back to positive territory.

Traders are now more focused on the contract for June delivery, making it more actively traded and therefore a better indication of how Wall Street views the price of oil. But this contract also fell, dropping 21 per cent to US$16.14, after earlier in the session sinking below US$15. The contract for July delivery fell roughly 11 per cent to US$23.42.

Brent crude, the international benchmark, for June delivery fell to as low as US$18.10, its lowest since November 2001. At 1200 GMT, it was down 18 per cent at US$20.98.

The May futures contract expires on Tuesday, meaning traders who buy and sell the commodity for profit needed to find someone to take physical possession of the oil.

But with the glut in markets and storage facilities full, buyers have been scarce.

The negative prices revealed a fundamental truth about the oil market in the age of coronavirus: The world's most important commodity is quickly losing all value as chronic oversupply overwhelms the world's crude tanks, pipelines and supertankers. Ultimately, traders were left desperate to avoid having to take delivery of actual oil because nobody needs it and there are fewer and fewer places to put it.

GLOBAL ACCORD

Despite the Opec+ deal to cut 10 per cent of global production, lauded by United States President Donald Trump little more than a week ago, the oil market's crisis is worsening. The rout will send a deflationary wave through the global economy, complicating the task facing central banks trying to keep economies afloat as the pandemic continues to paralyse business and travel worldwide.

The price collapse could redraw the global map of power as petrostates like Russia and Saudi Arabia, which enjoyed a resurgence over the last 20 years thanks to an oil windfall, see their influence diminished. Exxon Mobil, Royal Dutch Shell and other oil giants are ripping up business plans, desperate to preserve cash.

WTI is the world's most traded financial oil contract, a benchmark followed from Zurich to New York to Tokyo. But when each month a futures contract nears expiry and traders roll their positions into further-out contracts, the real, physical world of WTI becomes very small - centered on Cushing, an oil town in Oklahoma where a massive hub of pipelines and storage tanks serves as the actual delivery point for barrels.

In the past three weeks, crude has been flowing into Cushing at a breakneck speed, averaging 745,000 barrels a day and taking in more oil than a medium-sized European nation like Belgium consumes. At that rate, the tanks there will be full before the end of May, something that has never happened before.

ETF FEVER

The days before expiry are often volatile as traders make the shift from a paper to a physical market. Until a few days ago, the May contract had been supported by huge financial flows by retail and institutional investors pouring money into oil through exchange-traded funds.

The largest crude ETF, known as the US Oil Fund, received billions of dollars in fresh funds in recent weeks, accumulating a fifth of all the outstanding contracts in the May futures contract. But last week, it rolled its position into the June contract, and evaporated from May. Without the fund, the contract was abandoned to the the forces of physical supply and demand.

As the market opened early in Asia's Monday morning, the May contract traded at US$17.85. As New York traders were firing up workstations in their makeshift home offices, it was below US$15.

Then prices really started to slide, making history all the way down. By 8am New York time, the decline had reached 37 per cent, the biggest intraday drop since the futures started trading in 1982. At around 11am, it passed the low of US$10.35 set in the oil bust of 1998. About an hour later, it took out US$10 a barrel.

'NOT A SINGLE BID'

When CME Group, which runs the exchange where WTI futures trade, said prices would be allowed to go negative, the selling accelerated. By 1.50pm the contract was below US$1 a barrel. Less than 20 minutes later, prices went below zero for the first time and just kept falling.

"No bids. Mental!" said one trader at a top merchant in a vain attempt to explain the collapse as prices went negative. "No bids; not a single bid," said another one in London. "Ridiculous," said a third senior trader in Geneva.

The contract settled at minus US$37.63, a drop of US$55.90. And there's still another day of trading to come before it finally expires.

"The May crude oil contract is going out not with a whimper, but a primal scream," said Mr Daniel Yergin, a Pulitzer Prize-winning oil historian and vice-chairman of the research and information company IHS Markit.

Even discounting the oddity of the May contract's plunge into negative prices, the world of physical oil suggests widespread pain.

Many refineries and pipeline companies told producers on Monday that they would only take their oil if they were paid. The daily price bulletin from Enterprise Products Partners, one of America's largest pipeline companies, showed negative prices for all of the crude it buys. Another giant, Plains All American Pipeline, told producers the same.

Mr Bob McNally, a consultant and oil historian, said the energy market was getting "reacquainted with how the price mechanism for oil works" - and why "for most of oil history, the industry and governments strive to stabilise prices through supply control, be it a tolerated cartel, government regulation, or both."

The Opec+ coalition of oil producing countries has failed to stop the rout. Saudi Arabia, Russia and other producers announced a week ago a historic deal to cut global production by nearly a tenth, or 9.7 million barrels a day, from May. The US, Canada, Brazil and others have said their own production is also falling as companies stop drilling new wells.

For Mr Trump, who personally brokered the Opec+ deal, negative prices means more trouble in the US oil patch. Pressure is building within the Republican party to use trade barriers to save the shale industry, including placing tariffs on foreign oil.

But the market - negative prices and all - isn't waiting for Opec to cut production, or for tariffs to slow imports. Rather than being an isolated event, Monday's unprecedented oil market plunge serves as a warning of more pain to come.

"If global storage worsens more quickly," veteran Citigroup oil analyst Ed Morse said, "Brent could chase WTI down to the bottom."