A $106 billion industry looks for child workers – but it keeps missing them

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

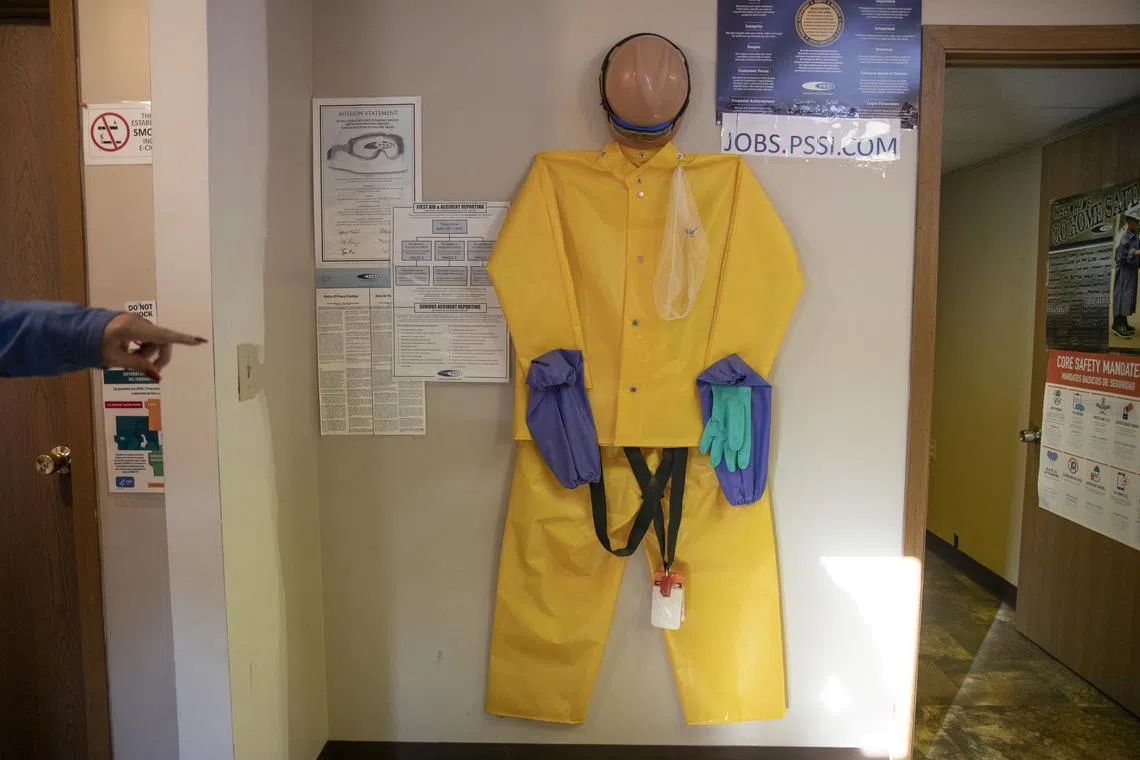

Protective equipment hangs in a recruiting office for Packers Sanitation Services, where migrant children were hired to clean slaughterhouses overnight, in Worthington, Minnesota.

PHOTO: NYTIMES

MINNESOTA - One morning in 2019, an auditor arrived at a meatpacking plant in rural Minnesota. He was there on behalf of national drugstore chain Walgreens to ensure that the factory, which made the company’s house brand of beef jerky, was safe and free of labour abuses.

He ran through a checklist of hundreds of possible problems, such as locked emergency exits, sexual harassment and child labour. By the afternoon, he had concluded that the factory had no major violations. It could keep making jerky, and Walgreens customers could shop with a clear conscience.

When night fell, another 150 workers showed up at the plant. Among them were migrant children who had come to the United States by themselves looking for work. Children as young as 15 were operating heavy machinery capable of amputating fingers and crushing bones.

Migrant children would work at the Monogram Meat Snacks plant in Chandler, Minnesota, for almost four more years, until the Department of Labour visited in the spring of 2023 and found such severe child labour violations that it temporarily banned the shipment of any more jerky.

In the past two decades, private audits have become the solution to a host of public relations headaches for corporations. When scandal erupts over labour practices, or shareholders worry about legal risks, or advocacy groups demand a boycott, companies point to these inspections as evidence that they have eliminated abuses in their supply chains.

Known as social compliance audits, they have grown into an US$80 billion (S$106 billion) global industry, with firms performing hundreds of thousands of inspections each year.

But a New York Times review of confidential audits conducted by several large companies shows that they have consistently missed child labour.

Children were overlooked by auditors who were moving quickly, leaving early, or simply not sent to the part of the supply chain where minors were working, the Times found in audits performed at 20 production facilities used by some of the most recognisable brands in the United States.

Auditors did not catch instances in which children were working on Skittles and Starburst candies, Hefty brand party cups, the pork in McDonald’s sandwiches, Gerber baby snacks, Oreos, Cheez-Its or the milk that comes with Happy Meals.

In a series of articles in 2023, the Times revealed that migrant children, who have been coming to America in record numbers, are working dangerous jobs in every state, in violation of labour laws. Children often use forged documents that slip by auditors who check paperwork but do not speak with most workers face to face. Corporations suggest that supply chains are reviewed from start to finish, but sub-suppliers such as industrial farms remain almost entirely unscrutinised.

The expansion of social compliance audits comes as the Labour Department has shrunk, with staffing levels now so low that it would take more than 100 years for inspectors to visit every workplace in the department’s jurisdiction once. For many factories, a private inspection is the only one they will ever get.

Auditors for several firms said they are encouraged to deliver findings in the mildest way possible as they navigate pressure from three different sources: the independent auditing firms that pay their salaries; corporations, such as Walgreens, that require inspections at their suppliers; and the suppliers themselves, which usually must arrange and pay for the audits.

The auditor who looked at the Minnesota jerky factory for Walgreens was Mr Joshua Callington. He has conducted more than 1,000 audits in the past decade.

He had not seen any child labour in the Minnesota factory. To keep to his work schedule, he had to leave for his next audit at 4pm, long before the late shift arrived. Spotting problems had also led to tension between Mr Callington and his employer, UL Solutions, which began as a safety testing business and expanded more than two decades ago into social compliance audits. The company took in US$2.5 billion in revenue in 2022 and is on the cusp of an initial public offering.

What Mr Callington saw as a commitment to his job, his firm seemed to see as overzealousness.

“The assessment is not meant to be a policing effort,” the UL Solutions employee handbook says.

After Mr Callington failed three Walgreens suppliers in 2017 and 2018 for abusive working conditions, the chain complained about his communication style and asked for him to be taken off its account. UL put him on a remediation plan for about a year.

Walgreens declined to comment on the incident, but said it only rarely asks for auditors to be removed. In response to questions about the Monogram factory, the company said it had cut ties with the supplier. Monogram said it is now using stronger age-verification procedures.

In the spring of 2023, Mr Callington flagged labour issues involving adult migrant workers at a warehouse that supplies Costco’s potatoes. The plant’s management complained that he was demanding and argumentative, and his supervisor barred him from returning. Mr Callington believed that the supplier objected to his finding 21 violations when the previous audit had found none. UL Solutions, which still employs Mr Callington, declined to comment on either incident.

A Darigold milk-processing plant in Portland, Oregon. Workers at the company, which processes milk for an association of 300 north-west dairy farms, said they often saw minors in the dairies.

PHOTO: NYTIMES

Night shifts, daytime audits

In dozens of interviews, auditors said that sometimes, their firms provide little more than a veneer of compliance for global corporations, which overstate how rigorously they review sprawling supply chains.

Auditors typically start their inspections in the morning and stay for about seven hours, even at 3,000-person factories that operate round the clock. In practice, this means that late afternoon and night shifts, where child labour violations most often occur, are almost never seen.

In 2023, the Department of Labour imposed a US$1.5 million fine against Packers Sanitation Services, which provides cleaning crews to slaughterhouses. Investigators found that the company was employing more than 100 children, including 13-year-olds, to clean back saws and head splitters overnight.

These plants had been supplying McDonald’s and Costco for years, and the corporations required regular audits. Some of those auditors noted that there was a large night shift run by the sanitation company, but said they had not been able to observe any of the workers. One auditor who was checking a Nebraska plant for Costco’s Kirkland brand beef spoke with 20 out of 3,500 workers – as is standard in much of the industry – and left at noon, an inspection showed. In another audit at the same plant, the inspector left at 1.30pm.

Costco and McDonald’s said in statements that they were strengthening their auditing standards. Packers said it had improved age verification of its workers.

But even if the auditors had stayed later at the plants, they might not have been able to talk privately with the migrant child workers, who largely speak Spanish or Indigenous languages of Central America. Auditing firms rarely provide interpreters.

In the absence of in-person interviews, auditors rely on paperwork. But children use forged documents. In the summer of 2023, for instance, a 16-year-old from Guatemala was killed while cleaning a Mississippi slaughterhouse that supplies Chick-fil-A. His documents said he was in his 30s. In a statement, Chick-fil-A said it was reviewing how it investigates violations at plants.

Research has shown that outside audits are less conclusive than companies suggest. A 2021 analysis of 40,000 audits by a Cornell professor found that nearly half had relied on forged or dubious documents. An earlier study that explored the industry’s financial conflicts of interest found that auditors report fewer violations when factories are paying the bill.

In a statement, UL Solutions said that audits provide a snapshot for companies, which are ultimately responsible for enforcing their standards. An audit, the statement said, “cannot and does not guarantee that an audited facility is in full compliance with requirements against which it was audited, and does not confirm nor certify compliance with laws”.

In the absence of thorough inspections, child workers can stay hidden for years.

Dairy cows in Washington’s Yakima Valley near the town of Sunnyside. Workers at Darigold, which processes milk for an association of 300 north-west dairy farms, said they often saw minors in the dairies.

PHOTO: NYTIMES

In 2020, an auditor visited a snack food factory in Geneva, Illinois, to do an inspection required by baby food giant Gerber. As it always had, Gerber’s report came back clear of child labour. The factory was also being regularly audited for the makers of Starburst and Skittles candies, Oreos and Cheez-Its. The companies behind those products said in statements that they had not seen indications of child labour in any inspections.

However, some migrant children were working on these products at the time. Among them was Efren Baldemar, who described getting the job with false identification at 14 years old. He was working from 10pm to 6.30am to help support his family in Guatemala, renting space in a house of strangers.

In the mornings, he went from the factory to ninth grade and often fell asleep at his desk. The pace on the assembly lines was gruelling. “If you didn’t keep up, the product would back up, and the machines would smoke,” he said.

The manufacturer, Hearthside Food Solutions, has been under federal and state investigations since the New York Times revealed child labour at other facilities in February 2023. In a statement last week, the company said it “has never knowingly employed underage labour in our facilities”. It said it could not find a record of Efren working at its plant.

Nagging questions

In his career, Mr Callington had never found a case of migrant child labour, which would trigger an automatic failing grade. But now, looking back, he suspected he had often audited plants where children were working.

Earlier in 2023, Mr Callington asked managers at UL Solutions if Costco or other corporations might be willing to start requiring unannounced night-time inspections. He pointed out news coverage that mentioned child labour raids at slaughterhouses.

“I have audited these locations and was never able to detect these issues, given that we are only present for the first shift,” he wrote.

A manager said she would raise the question with higher-ups. He never heard anything more about it. NYTIMES