Thousands of Indians keen on construction jobs in Israel despite safety concerns

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Job seekers trooping into a screening centre in north India's Rohtak on Jan 21. They were tested for potential roles as construction workers in Israel.

ST PHOTO: DEBARSHI DASGUPTA

Follow topic:

ROHTAK, Haryana – They waited patiently in padded jackets or with shawls wrapped around their torsos one recent morning at a public university in Rohtak. The haversacks on their backs were packed with certificates.

Mr Dayanand Kumar, 29, was among several hundred men queueing at a recruitment camp in the north Indian city.

Mr Kumar had turned up early for the third day in a row, hoping to show off his masonry skills to Israeli recruiters who are looking to India to replace thousands of deported Palestinian construction workers following Hamas’ attack on the country on Oct 7.

The lure of handsome pay in Israel has made these daily-wage workers, who mostly earn around 25,000 rupees (S$403) or less for 30 days of work, overlook the danger of working in Israel amid the continuing conflict there.

“We can’t run our house with the money we make here,” Mr Kumar, who has two daughters, told The Straits Times. “With 25,000 rupees, do we feed our children or ourselves?”

Haryana Kaushal Rozgar Nigam, a state government recruitment agency that co-organised the job camp, has advertised a monthly pay of around 137,000 rupees for various construction sector roles in Israel. Workers will also be offered other benefits, such as four days of leave every month.

More than 2,000 workers were screened at the six-day camp in Rohtak that began on Jan 16. More such recruitment drives are planned in the coming weeks, as Israel speeds up efforts to recruit foreign workers.

Job seekers had trooped in from across the state, including those with no or little experience in construction. Many also came from neighbouring states such as Punjab and Rajasthan but were turned away after the first two days, following demands that only those from Haryana be screened at the camp organised by the local state government.

This is not the only controversy dogging this recruitment drive. There are concerns over the workers’ safety in Israel, and labour unions in India are worried that workers from the country could become “tools in the hands of Israel” to further its war efforts against Palestine, including by getting them to build military-related infrastructure or construct illegal settlements on occupied territory.

But all this is of little worry to the workers at the camp, who consider unemployment and poverty in India a bigger threat than the conflict in Israel.

“There you will die once; here you die daily, every moment,” said Mr Ashok Rohilla, 29, who is desperate for a job that will pay him more than the 18,000-odd rupees he earns every month as a mechanic in an automotive spare parts manufacturing company. He has little left over after paying his rent and supporting his mother, who lives with him.

“We are dying here. Better we die there; at least we will get something,” added 36-year-old Manish Kumar, who worked in Malaysia as a carpenter and returned nine months ago to be with his family in Haryana.

Since then, he has managed to earn just about 15,000 rupees every month, making him desperate to get out of India again.

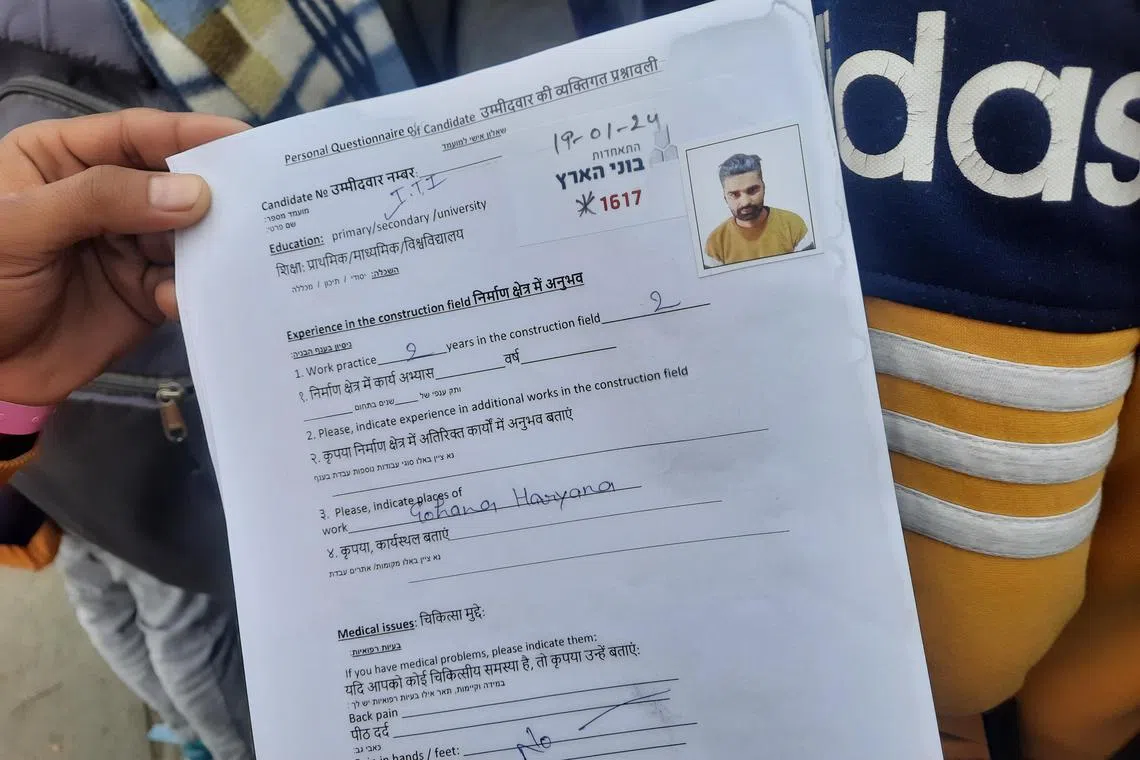

A worker shows his application form at the camp in Rohtak.

ST PHOTO: DEBARSHI DASGUPTA

According to the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy, a private economic think-tank, the unemployment rate in the country was 8.65 per cent in December 2023, but joblessness among those aged 20 to 24 for the October-December 2023 quarter grew to 44.49 per cent, up from 43.65 per cent in the previous quarter.

The fight for jobs is particularly contentious in Haryana, which has had one of the highest unemployment rates in the country.

In 2021, the state government approved a piece of legislation mandating that private companies reserve 75 per cent of their jobs that paid less than $484 per month for residents of the state. The law was struck down by the High Court of Punjab and Haryana in 2023.

The lack of meaningful employment opportunities in India has made the country’s youth, many of whom have poor levels of education and skills training, desperate for lucrative opportunities abroad.

Mr Dayanand Kumar, 29 (third from left) was among several hundred Indian construction workers queuing up at an Israeli recruitment camp in the north Indian city of Rohtak, on Jan 21, 2024.

ST PHOTO: DEBARSHI DASGUPTA

In May, Israel and India inked an agreement to allow 42,000 Indian workers to work in the Jewish state. On Dec 19, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu also “discussed advancing the arrival of foreign workers from India to Israel” during a telephone conversation with his Indian counterpart Narendra Modi.

Mr Shay Pauzner, deputy director-general of the Israel Builders Association, told ST in December that the goal was to bring 10,000 workers to Israel as quickly as possible because “time is running (out) and we are already in a big, big problem financially”. He refused to comment for this story.

Around 82,000 Palestinians worked in Israel’s construction industry before the Hamas assault, accounting for a third of the sector’s workforce. Their absence has crippled the industry, one of the country’s biggest economic sectors, with a market size valued at US$71 billion (S$94 billion) in 2022.

But Indian trade unions have opposed the move to replace Palestinian workers with Indian workers in a conflict zone.

Ms Amarjeet Kaur, general secretary of the All India Trade Union Congress (AITUC), the oldest trade union federation in the country, noted that the government has regularly evacuated Indians stuck in war zones, including more than 1,300 Indian nationals from Israel after the latest bout of conflict broke out with Hamas.

“But here the opposite is being done... The government (of India) should not use our workers as tools or as guinea pigs for political purposes,” she told ST.

“I am all for giving our youth employment opportunities but what we are seeing in this case is distress migration. Why should the government encourage this? It should instead provide them jobs here. Why has it failed to provide them jobs?”

Mr Ashok Rohilla, 29, is desperate for a job that pays him more than the 18,000 or so rupees he earns every month.

ST PHOTO: DEBARSHI DASGUPTA

The AITUC, with support from other labour unions, plans to approach the courts in India to stop the recruitment drive.

The Ministry of External Affairs did not respond to a request for comment from ST but its spokesman, Mr Randhir Jaiswal, told a media briefing on Jan 18 that the government was committed to the safe and legal mobility and migration of Indians and noted that labour laws in Israel “are very strict, robust”.

The involvement of the government has brought some assurance for many workers and their families. A poster featuring Haryana Chief Minister Manhohar Lal welcomed candidates at the recruitment camp in Rohtak. “Transforming Haryana through a ‘Go Global Approach’,” it read.

“The Indian government would surely have discussed the safety of its workers with Israel,” said Mr Sohan Lal, 53, who had come to the camp with his 30-year-old son, who works as a plasterer.

Mr Sanjeev Kumar Yadav, a 35-year-old driver, travelled more than 700km to the camp in Rohtak, from Allahabad in the state of Uttar Pradesh.

ST PHOTO: DEBARSHI DASGUPTA

Among the many who turned up at the camp in Rohtak on Jan 21 was Mr Sanjeev Kumar Yadav, a 35-year-old driver, who had taken a train from Allahabad, more than 700km away in the state of Uttar Pradesh. He had travelled more than 24 hours, lured by the possibility of high pay in Israel.

Mr Yadav hung around despite hearing that outsiders were not being screened. “Maybe I can get a job as an assistant to a mason,” he said. “From 15,000 rupees, if I am able to earn around 135,000 rupees, my problems will disappear.”