A battle is raging for hearts and minds over the ongoing Russian invasion of Ukraine.

The stakes are high. For how this gut-wrenching, live-on-your-mobile war plays out will have an impact not only on the geopolitics of Europe, but also on the prospects for growth and prosperity around the world for years to come.

Beyond that is also the question of the shape of the world order that might follow.

In 1989, as a young student, I was transfixed by the television images of the fall of the Berlin Wall, with people rushing across the border to embrace a freedom they had been denied for generations. That marked the end of the Cold War, and unleashed a wave of globalisation, that many countries, Singapore included, rode on to better lives.

History has ended, thinkers such as Francis Fukuyama declared then, meaning that the world had reached a culmination of the age-old contest of ideologies, with the triumph of liberal democracy. The world marched to global peace and prosperity, led by the United States as the sole superpower. It all sounded a tad too good to be true, since not all countries could be, or wished to be, liberal democracies in the American mould.

Then came Sept 11, 2001, when searing images of planes crashing into New York's World Trade Centre signified the flaring up of deep-seated religious hatred that spawned terrorists ready to kill others and themselves, in a misguided clash of civilisations.

Just as those proved to be pivotal moments for the world, the decision by Russia's President Vladimir Putin to send his troops into Ukraine on Feb 24, 2022, will be another turning point, even if this one is proving to be more long-drawn than many anticipated, not least Mr Putin.

Some say it marks the "end of the end of history", and a return to geopolitical rivalries as we knew it. Or less grandiloquently, an end to the "peace dividend" that countries enjoyed, which enabled them to divert precious tax dollars to priorities other than defence.

By this reckoning, the "holiday from history" is over. Almost overnight, there have been marked shifts in defence postures in Germany and Japan, with even Sweden and Finland rethinking their commitment to neutrality.

At troubled times like these, fraught discussions arise about how it all came to this, who is responsible - or to blame - and how the world might extricate itself from these strategic conundrums.

A leading voice in this ongoing debate is the well-known international relations scholar, Professor John Mearsheimer of the University of Chicago. For several years now, he has been railing against United States foreign policy, charging that it is both misguided and dangerous. This is because false hopes have been given to some Eastern European states, not least Ukraine, about the strategic options open to them, he says.

Arguing that America is "principally responsible" for the current crisis, he points to the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation's (Nato) summit in Bucharest in April 2008, "when Mr George W. Bush's administration pushed the alliance to announce that Ukraine and Georgia 'will become members'".

"Russian leaders responded immediately with outrage, characterising this decision as an existential threat to Russia and vowing to thwart it."

The US ignored these protests, and continued to draw Ukraine closer to the European Union and Nato, an "over-reach" that raised eyebrows in US defence circles and among some European leaders, he adds.

"For Russia's leaders, what happens in Ukraine has little to do with their imperial ambitions being thwarted; it is about dealing with what they regard as a direct threat to Russia's future.

"Mr Putin may have misjudged Russia's military capabilities, the effectiveness of the Ukrainian resistance and the scope and speed of the Western response, but one should never underestimate how ruthless great powers can be when they believe they are in dire straits."

This view has found a following among those who subscribe to the realist school of geopolitics. It is premised on the notion that geography, history and politics ineluctably shape the behaviour of states and statesmen.

Realists often scoff at so-called "21st century" leaders, such as former US president Barack Obama, for being liberal, idealistic and naive, failing to grasp the lessons that might be drawn from centuries of balance of power politics.

Such views have been making the rounds online. They have been shared spontaneously by some who find the arguments compelling, but are also being pushed actively by others eager to promote the narrative that the current crisis has been instigated by the US and its Western allies. The latter are charged with provoking, wittingly or otherwise, a legitimate Russian reaction against their thinly veiled and self-serving agendas for continued global domination.

Now, I have long shared the view that it is best to be robust and clear-eyed about the ways of the world, especially on matters of defence and diplomacy.

Yet, this takes us only so far, as there is so much more to the unfolding Ukraine story.

Consider the views of the highly respected historian and Russia expert, Professor Stephen Kotkin of Princeton University. He argues that Mr Putin's response was prompted not so much by US moves to expand Nato, nor its failure to acknowledge Russia's unhappiness over it.

Disagreeing with Prof Mearsheimer, and others like him, he says: "The problem with their argument is that it assumes that, had Nato not expanded, Russia wouldn't be the same or very likely close to what it is today.

"What we have today in Russia is not some kind of surprise. It's not some kind of deviation from a historical pattern. Way before Nato existed - in the 19th century - Russia looked like this: It had an autocrat. It had repression. It had militarism. It had suspicion of foreigners and the West. This is a Russia that we know, and it's not a Russia that arrived yesterday or in the 1990s. It's not a response to the actions of the West. There are internal processes in Russia that account for where we are today.

"I would even go further. I would say that Nato expansion has put us in a better place to deal with this historical pattern in Russia that we're seeing again today. Where would we be now if Poland or the Baltic states were not in Nato? They would be in the same limbo, in the same world that Ukraine is in."

The upshot of Mr Putin's actions is to reassert Russia's belief that it has a right to demand that its neighbours bend to Moscow's will, forever accepting the need to put the Kremlin's security concerns - some would say, paranoia - ahead of their own peoples' aspirations and interests.

So, whereas Prof Mearsheimer asserts that it was foolhardy for Western leaders to hold out hopes to Russia's neighbours that they too might have a choice of whom they wished to form trade or security alliances with, Prof Kotkin raises this critical question: On what grounds are they to be denied such freedoms?

Could world leaders have told the Poles, Estonians or Ukrainians to just be "realistic", and not harbour any hopes of charting their own course, for fear of upsetting the neighbours? Should they have been told to pipe down when they voiced desires to become developed democracies, simply because doing so would rouse Russian fury?

Now, here's the rub: Imagine for a moment, that world leaders had said as much to Singapore's founding fathers in the 1960s, that they too should be more "realistic" in pushing their people's desires to live freely, with all races treated fairly and equally, rather than being subjected to the majoritarian calculus of the dominant political players of that time?

Or what are today's generation of Singaporeans to tell our children to do, in the event that some time hence, some crazed strongman decides the moment and opportunity has come to revisit "historical mistakes" and forcibly redraw maps, simply because he has the inclination and will to do so?

Should they just bow their heads, grit their teeth, and accept the inevitable, given how small and vulnerable the country is?

I think not.

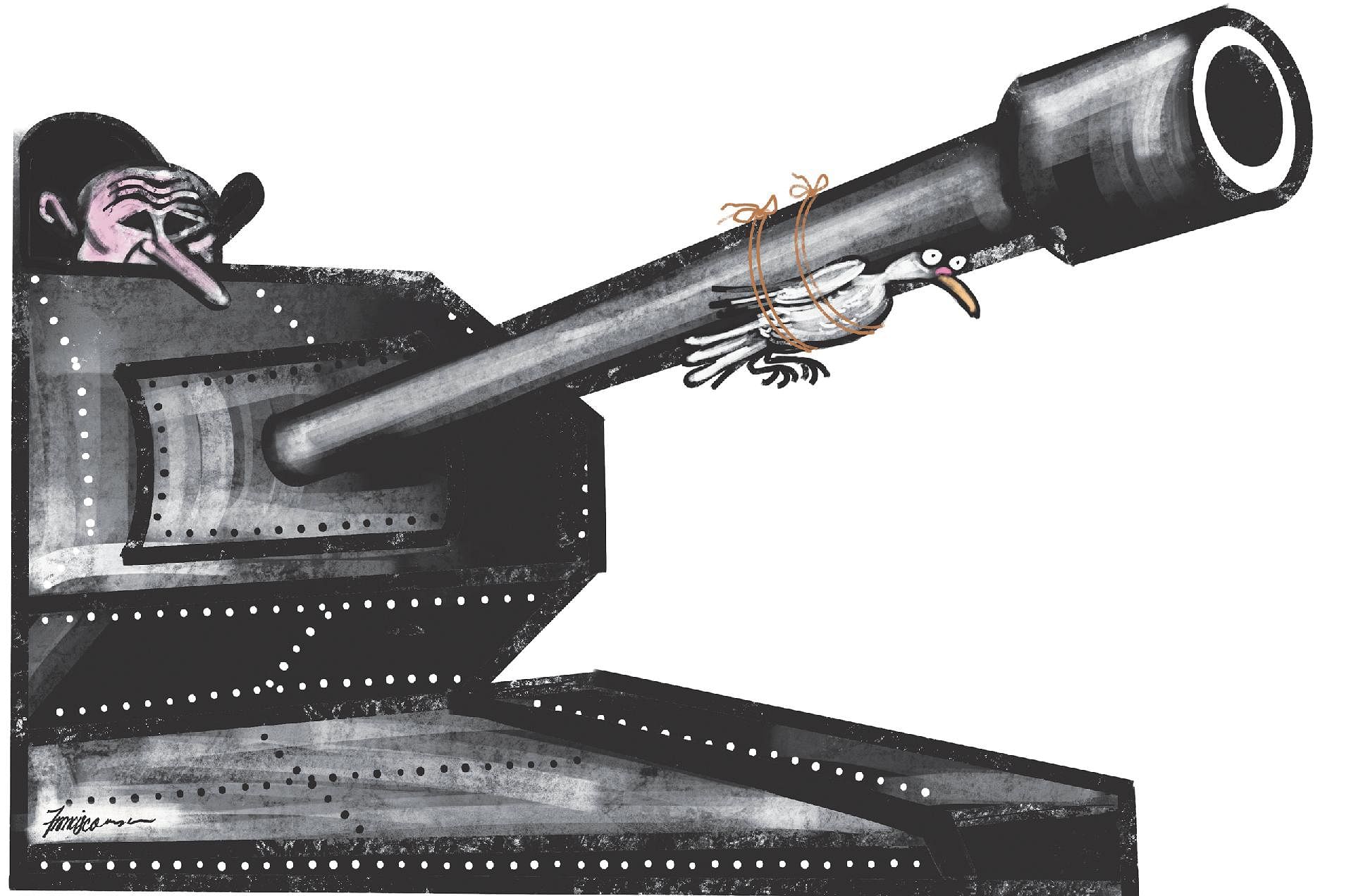

Let's be clear: Whatever one makes about the legitimacy of Mr Putin's security concerns, that surely went up in smoke with the first firing of Russian missiles and movement of its tanks into Ukraine.

Or, to put it more simply, however concerned or aggrieved one might be about a neighbour's behaviour, it does not justify anyone choosing to lob things over the fence or assaulting his children.

In doing so, Russia's - or, more accurately, Mr Putin's - actions are a blatant assertion that his grievances trump all other interests, principles and concerns.

Never mind the suffering the war is imposing on millions of fellow Slavs in Ukraine whom he claims as his kinsmen. Never mind that millions around the world are still struggling to cope with the health and economic impacts of a deadly pandemic.

Never mind that the world faces an existential climate challenge, which needs to be addressed, now, collectively and decisively.

Never mind that his flagrant nuclear threats risk an unthinkable conflagration that puts the planet at risk.

To accept - or support - Russia's case for war amounts to saying that a state or a leader can impose his interests, however questionable, over the rights and concerns of others, simply because he has the wherewithal and the will to do so, regardless of the consequences for everyone else.

That, to put it plainly, is both intellectually bogus and morally bankrupt.

So too the smug suggestion that to harbour hopes that humans might learn to live in peace, even in the face of geopolitical rivalries, is "unrealistic and naive".

Of course, leaders and states have been known to pursue horrendous agendas when they fall under the sway of their lesser angels. It is best to be clear-minded about that, and prepare to deal with it, if and when necessary.

But you don't have to be a pacifist to cherish the belief that humans are capable of progress and societal evolution, with peoples of different colours and creeds learning to live and work together for the common good.

That fundamental belief, by the way, underpins Singapore's very reason for being.

Indeed, the need for such enlightened thinking is all the more pressing today, given the perplexing challenges the world faces.

Financial Times columnist Martin Wolf summed this up well in his column last week, when he urged world leaders to stand together against the forces seeking to pull the East and West apart, and to "try not to abandon everything achieved in the past three decades".

"We are not at war with ordinary Russians and Chinese people who simply hope for a better future," he wrote. "Not least, we need to remember the wider concerns all humans share - the global environment, managing pandemics, economic development and peace itself.

"We cannot survive without cooperation. If Putin's madness proves anything, it is that. The world of 'might is right' is not a world we can safely live in. As his nuclear threats show."

Pointing to the risk of a new Cold War, pitting democratic and free trading nations against a group of angry autarkies and autocracies, he adds: "A prolonged bout of stagflation seems certain, with large potential effects on financial markets. In the long term, the emergence of two blocs with deep splits between them is likely, as is an accelerating reversal of globalisation and sacrifice of business interests to geopolitics. Even nuclear war is, alas, conceivable."

So, amid the fog of war that is, sadly, now unfolding, this much remains as clear as a spring day in Kyiv: Mr Putin's decision to go to war cannot be accepted, supported, or allowed to go unchecked. Nor should any credence be given to his claims of Russia's right to impose its views of how the world should be shaped, however righteous he might think his cause.

Doing so would be to herald a dangerous, cynical, and ultimately, unsustainable world, where might is right, and the deeply human hope for peace and progress is folly.