SINGAPORE - While the military is undeniably a big part of the current crisis in Myanmar, it must also be part of the solution if the country is not to fragment further. In this regard, Asean can play a key role in putting peer pressure on Myanmar, said Mr George Yeo.

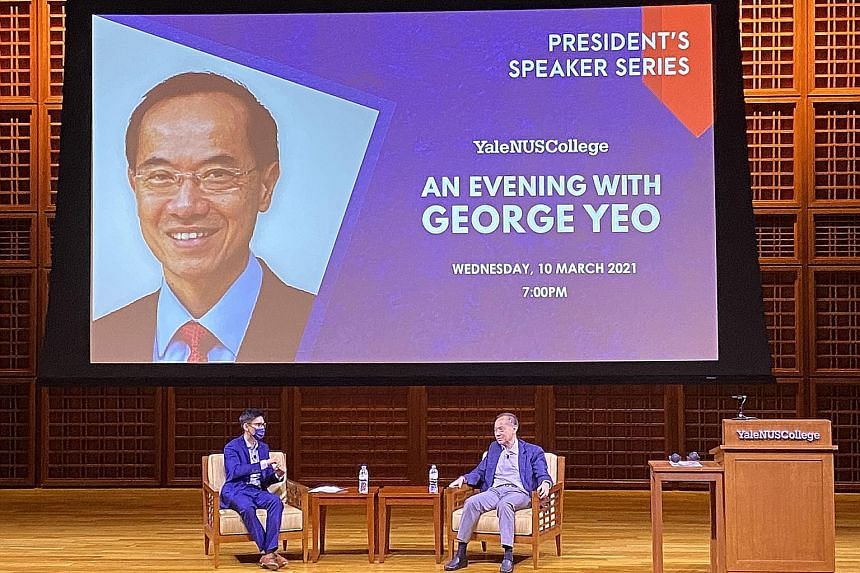

Singapore's former foreign minister said this on Wednesday (March 10) at the Yale-NUS College President's Speaker Series, a series of public lectures featuring key global personalities.

Mr Yeo said he is not entirely pessimistic about the situation in Myanmar, even though it is clearly "heartbreaking" and "an enormous setback" following many years of democratic transition.

Myanmar's armed forces seized power from the elected government on Feb 1, citing alleged voter fraud in the November 2020 election to justify the coup. The military, led by Senior General Min Aung Hlaing, also detained state counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi and members of her National League for Democracy (NLD) party.

Security forces have cracked down with increasing force on nationwide protests, with over 60killed and thousands arrested. A watchdog said this week that a second NLD official has died in custody following alleged torture.

Mr Yeo, who was foreign minister from 2004 to 2011, said the key to a compromise is to involve the army, not to dissolve it, as Western powers had done in Libya and Iraq.

For example, he said, it was a "fatal decision" to dismantle former Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein's Baathist army shortly after the 2003 US invasion. Baghdad's post-invasion military lost some of its best commanders and troops, creating a vacuum which was filled by warring factions and eventually terror group Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS).

Likewise, Myanmar is made up of 135 officially-recognised ethnic groups, many of which have their own armies and the capability to incite war.

Hence, there can be no solution without the army, Mr Yeo said. "However unpleasant, however difficult, you still need a compromise and a power balance."

He added that while the immediate reaction would be one of euphoria if the army is removed, what happens five years, 10 years from now is a question mark.

"There's a fair chance that Myanmar would become a Libya or Iraq, and its divisions would drag in all its its neighbours, including India, Bangladesh and us. We would have years and decades of trouble."

He said that based on statements made by the military government, the current state of affairs may not be permanent. The military had declared a one-year state of emergency on Feb 1, and said it would hold a "free and fair general election" after the emergency is over.

Asean, he said, must exert pressure on Myanmar as it had in the past - not by condemning it, but by insisting that it put time markers on its roadmap to democracy.

"This is the role Asean must play - peer pressure on the military government. Hold them to the one-year programme and say, 'Look, how are you going to return Myanmar back to what it was?'" he said.

"If you want to fix the election mechanism, tell us how you want to fix it. And maybe after you've fixed it, let there be Asean monitors to ensure what you promised us will be properly carried out."

Mr Yeo noted that Western governments had turned against Ms Suu Kyi in recent years for her failure to condemn the military atrocities against Muslim Rohingyas in Rakhine State. She also defended her country against claims of genocide at the International Criminal Court in The Hague.

But it is not clear that the recent leadership change will aid the Rohingya cause, he said, as most Myanmar people do not recognise them as a separate ethnic group. "They see them as a legacy of British colonial rule, when Myanmar was part of the (British) Raj and all the top jobs were held by Indians... It's a legacy of history."

During the session moderated by Yale-NUS political scientist Chin-Hao Huang, Mr Yeo also touched on US-China rivalry, the rise of nationalism, and Singapore's response to Covid-19.

"When you have something big like (Covid-19), all social systems come under great stress and societies respond... People become selfish and they ostracise one another," he said.

The desire among countries to fault-find, he explained, has its roots in the fear of a rising China, which threatens the dominance of the US and other Western powers.

"In a sense, Covid-19 is accelerating history. Tensions which were building up anyway are now quickly reaching a head," he said.

"For those of us who are (caught) in between like Singapore, we have to be very conscious of the forces being unleashed, and the fact that different societies are responding with varying success to Covid-19."

Being a hub, Mr Yeo said, Singapore would lose the very basis of its existence unless it reopens. The key task is therefore to open up borders safely and reestablish trust.

Because hubs which are trusted will draw a disproportionate amount of traffic compared with those which are not trusted, the problem which Singapore faces is also a "great opportunity".

"Trusted hubs can network together, creating an almost Covid-19-free Schengen," he said, citing the zone where 26 European countries have abolished their internal borders to enable free and unrestricted movement of people.

Mr Yeo stressed the importance of international cooperation despite rising tensions.

He said: "Rudyard Kipling said, 'East is East and West is West, and never the twain shall meet.' But the twain must meet."