Suez blockage puts spotlight on mega ships and the problems they pose

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

The Ever Given can haul more than 20,100 steel boxes, making it one of the largest container ships.

PHOTO: EPA-EFE

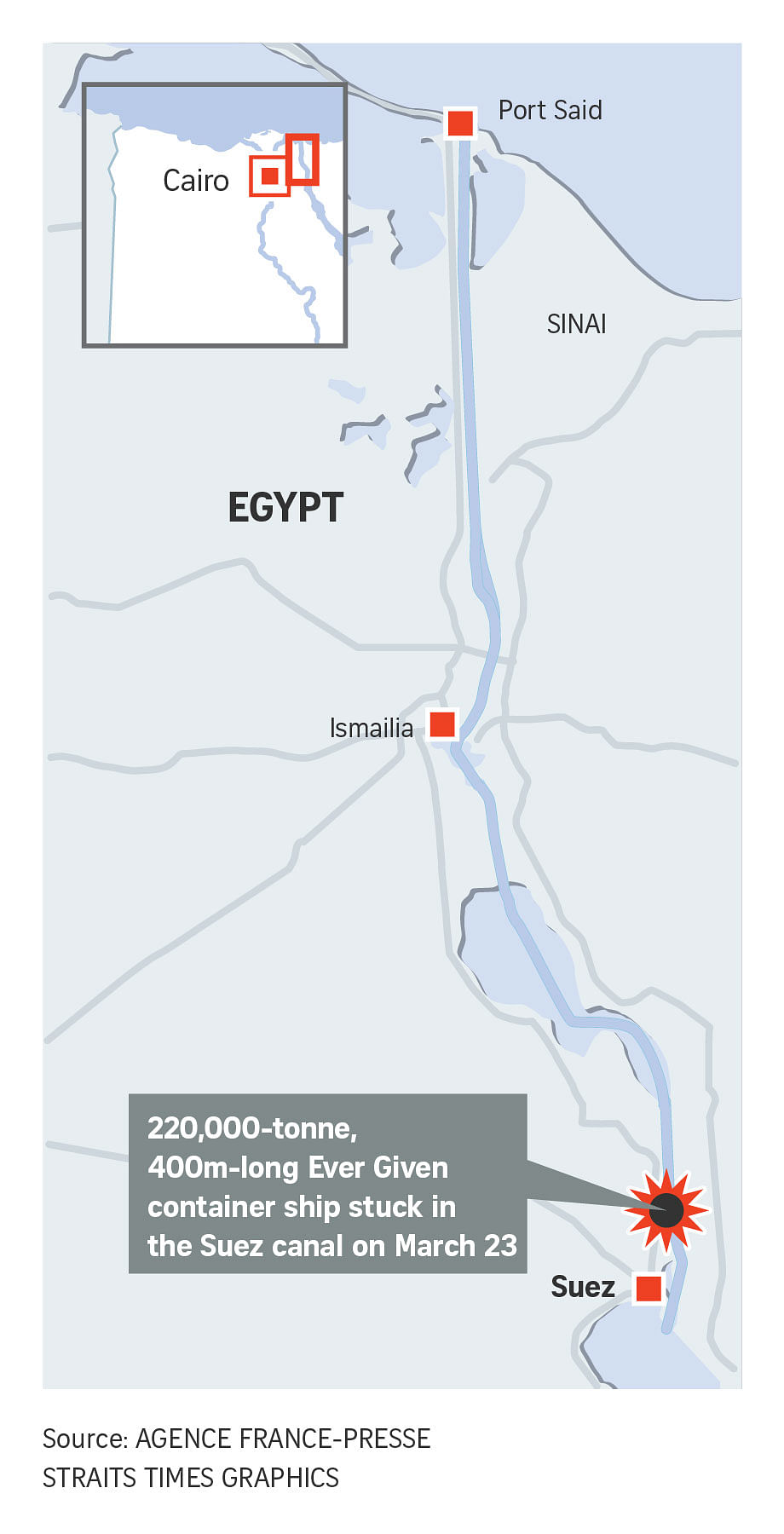

SEOUL (BLOOMBERG) - The maritime world went into overdrive this week to dislodge one of the world's biggest ships after it got jammed in Egypt's Suez Canal, laying bare the fresh challenges the industry must navigate as mammoth vessels play an ever larger role in global trade.

The container ship Ever Given got stuck across the canal early on Tuesday (March 23), and about 48 hours later, tugs and diggers are still struggling to get it afloat.

The Ever Given can haul more than 20,100 steel boxes, making it one of the largest container ships, according to Mr Jayendu Krishna, director of maritime advisers at the consultancy Drewry. Such vessels can be longer than the Eiffel tower, and bigger than three soccer fields.

Around the world, ships have ballooned in size because the industry has looked for economies of scale, but these mega vessels have also drawn concerns.

Shipping companies have used them to lower costs per unit, but that is putting pressure on ports to make their waterways deeper and spend on more cranes, said Mr Park Moo-hyun, a Seoul-based analyst at Hana Financial Investment.

Mr Clive Reed, founder of Reed Marine Maritime Casualty Management Consultancy, said there is a risk of large container ships running aground in the Suez Canal if travelling at high speed.

"I am not surprised this has happened," he said. "Once it is out of dead centre, it will get sucked to one side or another, hence sinking sideways into the canal embankment."

The Suez Canal Authority said a lack of visibility due to bad weather and a sand storm led to the ship to lose control and drift. The Ever Given "was grounded accidentally after deviating from its course due to suspected sudden strong wind", Taiwan-based Evergreen Line, the time charterer of the vessel, said via e-mail.

The Suez Canal has had to contend with ever larger container vessels with the average tonnage per ship rising from 93,500 tonnes in 2015 to 119,000 tonnes in the 12 months to Feb 28 last year, S&P Global noted this week.

Globally, there are about 180 vessels that can each carry more than 15,000 containers, according to analyst Um Kyung-a from Shinyoung Securities in Seoul. The industry's appetite for these big ships was sparked when A.P. Moller-Maersk took delivery of Emma Maersk, which could carry 15,000 containers, in 2006. Since then, shipping companies have been competing to build bigger ships.

At least 47 more ultra-large container vessels are expected to be delivered by 2024, according to research firm Drewry. A vessel that can carry 20,000 containers costs about US$144 million (S$194 million) and those carrying 23,000 containers cost more than US$150 million, Drewry estimates.

Companies like CMA CGM and HMM expect to take deliveries of these ships almost every other month this year.

Images showing the fully loaded Ever Given blocking the canal put a spotlight on a container shipping industry that has been straining at full capacity for the past six months, trying to deliver goods as consumers, restricted from travelling because of Covid-19, spend more on household goods instead.

Managing big ships such as the Ever Given can be particularly hard when there are big wind gusts in places like the Suez Canal, according to a former crew member. The ship's enormous size means it can be pushed into wind gusts and turned sideways fast, he said.

More than 180 vessels are caught up in the traffic snarl in both directions in the canal, a global trade artery. Refiners across the world use the route heavily, raising worries that global energy markets could be affected by the blockage.

Growing ship sizes also pose a problem for ports on the United States West Coast, where Los Angeles and Long Beach, California cannot easily handle ships holding more than about 15,000 containers. That means the super-sized vessels mainly ply between Asia and Europe, with places such as Shanghai, Singapore and Rotterdam being some of their preferred ports of call.

Currently, South Korea's HMM operates 12 of the world's biggest container vessels, with each able to carry as much as 24,000 20ft containers. Other companies such as CMA CGM, Mediterranean Shipping, Cosco Shipping and Orient Overseas Container Line also operate mega vessels that can each carry more than 20,000 boxes.

Building even bigger ships would not be likely because it will require changes in the design and more investments will be needed to be made at ports, said Mr Um.

"The Ever Given incident has raised the need to relook at some of the contingency plans these canals have to prevent this from happening again," he said. "A lot of large vessels do go through the Suez Canal every day but when one gets into trouble, like what's happened now, the impact is just too big."

Global trade in merchandise has recovered to pre-pandemic levels as the coronavirus triggered demand for household goods. Ports are congested from Los Angeles to Rotterdam as the pandemic affected land transport and operations at ports. All that has fuelled high demand for container ships.

Meanwhile, there were bottlenecks on the US West Coast that spread across the world and also triggered a jump in rates. Spot rates to haul a 40ft container from Shanghai to Los Angeles almost tripled last year, according to the World Container Index.

Large ships remain one of the most important cogs in the world of global trade. Still, groundings are far from the only challenge to beset major shipping vessels, S&P noted this week.

One of the industry's most recent challenges has been a series of losses at sea during the winter storm season in the Pacific that have led at least five ultra-large vessels to lose containers, the firm said.

The Suez incident is an example of the fragility of maritime commerce and global supply chains that should be addressed, said Mr Ian Ralby, chief executive officer of IR Consilium, a maritime law and security consulting firm that works with governments.

"By the time canals are completed, they're always too small to handle the biggest ships," he said. "This forces us to look at where infrastructure is today and where we think it ought to be, otherwise we'll never get it caught up and in alignment."