Covid-19 pandemic: What's next for the world?

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Experts believe that the virus will never go away entirely, and instead will continue to evolve to create new waves of infection.

PHOTO: EPA-EFE

NEW YORK (BLOOMBERG) - As a virus-weary world limps through the third year of the outbreak, experts are sending out a warning signal: Don't expect Omicron to be the last variant we have to contend with - and don't let your guard down yet.

In the midst of a vast wave of milder infections, countries around the world are dialling back restrictions and softening their messaging.

Many people are starting to assume they've had their run-in with Covid-19 and that the pandemic is tailing off. That's not necessarily the case.

The crisis isn't over until it's over everywhere. The effects will continue to reverberate through wealthier nations - disrupting supply chains, travel plans and health care - as the coronavirus largely dogs under-vaccinated developing countries over the coming months.

Before any of that, the world has to get past the current wave. Omicron may appear to cause less severe disease than previous strains, but it is wildly infectious, pushing new case counts to once unimaginable records.

Meanwhile, evidence is emerging that the variant may not be as innocuous as early data suggest. There's also no guarantee that the next mutation - and there will be more - won't be an offshoot of a more dangerous variant such as Delta. And your risk of catching Covid-19 more than once is real.

"The virus keeps raising that bar for us every few months," said Dr Akiko Iwasaki, a professor of epidemiology at Yale School of Medicine.

"When we were celebrating the amazing effectiveness of booster shots against the Delta variant, the bar was already being raised by Omicron."

"It seems like we are constantly trying to catch up with the virus," she said.

It's sobering for a world that's been trying to move on from the virus with a new intensity in recent months. But the outlook isn't all gloom.

Anti-viral medicines are hitting the market, vaccines are more readily available and tests that can be self-administered in minutes are now easy and cheap to obtain in many places.

Nevertheless, scientists agree it's too soon to assume the situation is under control.

In six months' time, many richer countries will have made the transition from pandemic to endemic. But that doesn't mean masks will be a thing of the past. We'll need to grapple with our approach to booster shots, as well as the pandemic's economic and political scars.

There's also the shadow of long Covid.

"There is a lot of happy talk that goes along the lines that Omicron is a mild virus and it's effectively functioning as an attenuated live vaccine that's going to create massive herd immunity across the globe," said Dr Peter Hotez, dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston.

"That's flawed for a number of reasons."

Experts now believe that the virus will never go away entirely, and instead will continue to evolve to create new waves of infection. Mutations are possible every time the pathogen replicates, so surging caseloads put everyone in danger.

The sheer size of the current outbreak means more hospitalisations, deaths and virus mutations are all but inevitable.

Many people who are infected aren't making it into the official statistics, either because a home test result isn't formally recorded or because the infected person never gets tested at all.

Dr Trevor Bedford, an epidemiologist at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Centre in Seattle known for detecting early Covid-19 cases and tracking the outbreak globally, estimates that only about 20 per cent to 25 per cent of omicron infections in the US get reported.

With daily cases peaking at an average of more than 800,000 in mid-January, the number of underlying infections may have exceeded 3 million a day - or nearly 1 per cent of the US population, Dr Bedford estimates.

Since it takes five to 10 days to recover, as much as 10 per cent of people in the country may have been infected at any one time. He's not alone in projecting astronomical numbers.

At the current infection rate, computer modelling indicates more than half of Europe will have contracted Omicron by mid-March, according to Dr Hans Kluge, a regional director for the World Health Organisation.

Meanwhile, a sub-variant known as BA.2 is spreading rapidly in South Africa. It appears to be even more transmissible than the original strain and may cause a second surge in the current wave, one of the country's top scientists said.

And just because you've already had the virus doesn't mean you won't get re-infected, as Covid doesn't confer lasting immunity.

New evidence suggests that Delta infections didn't help avert Omicron, even in vaccinated people.

That would explain why places like Britain and South Africa experienced such significant outbreaks even after being decimated by Delta.

Reinfection is also substantially more common with Omicron than previous variants.

"With Omicron, because it has more of an upper respiratory component, it's even less likely to result in durable immunity" than previous variants, Dr Hotez said.

"On that basis, it's incorrect thinking to believe that this is somehow going to be the end of the pandemic."

Preparing for the next Covid strains is therefore vital.

"As long as there are areas of the world where the virus could be evolving, and new mutants arriving, we all will be susceptible to these new variants," said Professor Glenda Gray, chief executive officer of the South African Medical Research Council.

Lockdowns and travel curbs aren't going away, even if they are becoming less restrictive on the whole.

"The things that will matter there are whether we are able to respond when there is a local surge," said Dr Mark McClellan, former director of the US Food and Drug Administration and director of the Duke-Margolis Centre for Health Policy.

"Maybe going back to putting on more masks or being a little bit more cautious about distancing."

Inoculation is still the world's primary line of defence against Covid-19.

More than 62 per cent of people around the globe have gotten at least one dose, with overall rates in wealthy countries vastly higher than in developing ones.

At the current pace, it will take another five months until 75 per cent of the world's population has received their first shot.

But studies show one or two injections don't ward off the pathogen.

The best bet at this point is a booster shot, which triggers the production of neutralising antibodies and a deeper immune response. People inoculated with more traditional inactivated vaccines, such as the widely used shots from China's Sinovac Biotech, will need at least two boosters - preferably with different vaccines - to control the virus, Yale's Dr Iwasaki said.

In the next six months, more countries will contend with whether to roll out a fourth shot.

Israel has started and the US backs them for vulnerable people, but India is pushing back and refusing to "blindly follow" other countries.

While the virus won't be overwhelming hospitals and triggering restrictions forever, it's still unclear when - or how - it will become safe to leave on the back burner.

Experts Bloomberg News spoke to agree that in developed countries including the US and much of Europe, the virus could be well in hand by mid-2022.

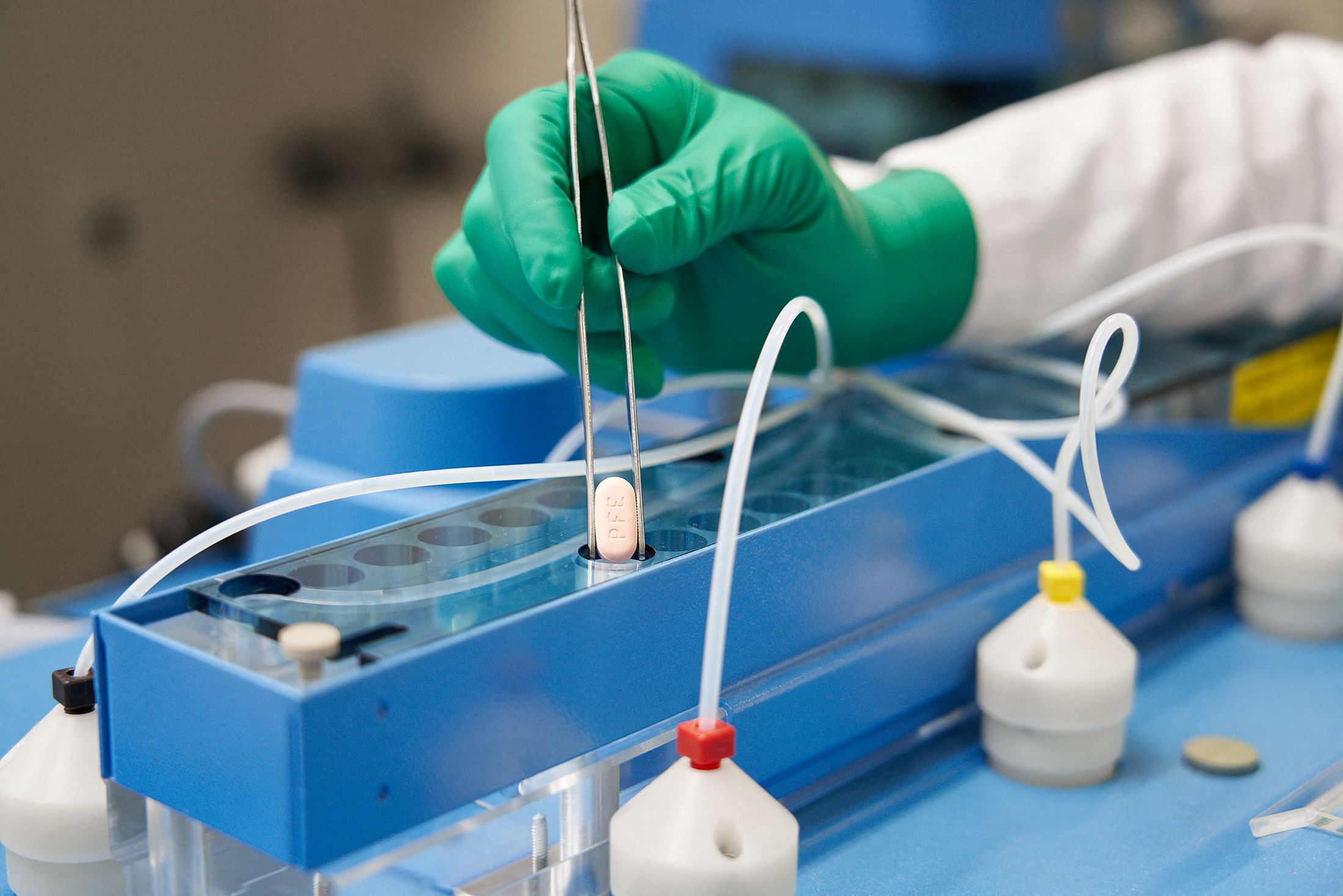

There will be better access to pills such as Pfizer's Paxlovid, rapid antigen tests will be more readily available and people will have become accustomed to the idea that Covid-19 is here to stay.

Dr Robert Wachter, chair of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, puts the odds at 10-to-one that by the end of February, most parts of the US and the developed world will no longer be struggling with severe outbreaks.

Vaccinations and new treatments, widespread testing and immunity as a result of previous infections are helping. Countries like Denmark are getting rid of all pandemic restrictions despite ongoing outbreaks.

"That is a world that feels fundamentally different from the world of the last two years," he said. "We get to come back to something resembling normal."

"I don't think it's irrational for politicians to embrace that, for policies to reflect that."

Elsewhere in the world, the pandemic will be far from over.

The threat of new variants is highest in less wealthy countries, particularly those where immune conditions are more common.

The Delta mutation was first identified in India while Omicron emerged in southern Africa, apparently during a chronic Covid-19 infection in an immunocompromised HIV patient.

"As long as we refuse to vaccinate the world, we will continue to see new waves," Dr Hotez said. "We are going to continue to have pretty dangerous variants coming out of low- and middle-income countries. That's where the battleground is."

Dr Amesh Adalja, senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins University Center for Health Security in Baltimore, sees the pandemic continuing into 2023 for parts of the developing world.

"For me, the transition from pandemic to endemic is when you're not worried about hospitals getting crushed," he said. "That will happen in most Western countries in 2022, and it will take a little bit longer for the rest of the world."

In parts of Asia, public health officials aren't even willing to consider calling the end of the pandemic. While most of the world now seeks to live alongside Covid, China and Hong Kong are still trying to eliminate it. After spending much of 2021 virtually virus-free, both places are currently dealing with outbreaks.

"We do not possess the prerequisites for living with the virus because the vaccination rate is not good, especially amongst the elderly," said Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam.

"I could not stand seeing a lot of old people dying in my hospitals."

Harsh virus restrictions including border closures and quarantines may well be in place until the end of 2022, though the higher contagiousness of the new variants is making that harder to maintain, as Hong Kong's current challenges show.

Walling out the virus completely, like a swathe of countries did early in the pandemic, may no longer be possible.

With so much of the world still mired in the pandemic, virus-related dislocations will continue everywhere.

The immense strain on global supply chains is only worsened by workers sickened or forced to quarantine as a result of Omicron.

The problem is especially acute in Asia, where much of the world's manufacturing takes place, and means global concerns about soaring consumer prices are unlikely to disappear any time soon. China's increasingly vehement moves to keep quashing Covid-19 are also becoming disruptive.

With many countries only partially open to visitors, international travel is still very far from what we considered normal in 2019.

Hospitals and health care systems around the world face a long, slow recovery after two years of monumental pressure.

And for some individuals, the virus may be a life sentence.

Long Covid sufferers have now been experiencing severe fatigue, muscle aches and even brain, heart and organ damage for months.

How long will we be dealing with the long-term ramifications of the virus?

"That's the million-dollar question," South Africa's Prof Gray said. "Hopefully we can control this in the next two years, but the issues of long Covid will persist. We will see a huge burden of people suffering from it."

Over the coming months, a sense of what living permanently with Covid-19 really looks like should take shape.

Some places may forget about the virus almost entirely, until a flareup means classes are cancelled for a day or companies struggle with workers calling in sick. Other countries may rely on masking up indoors each winter, and an annual Covid-19 vaccine is likely to be offered in conjunction with the flu shot.

To persist, the virus will need to evolve to evade the immunity that's hitting high levels in many parts of the world.

"There could be many scenarios," Yale's Dr Iwasaki said.

"One is that the next variant is going to be quite transmissible, but less virulent. It's getting closer and closer to the common cold kind of virus."

If that evolution takes a more toxic path, we will end up with a more severe disease.

"I just hope we don't have to keep making new boosters every so often," she added. "We can't just vaccinate everyone around the world four times a year."

"It's really hard to predict."