On the food trail in the Little Red Dot

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Fast-food chain McDonald’s opened at Liat Towers in 1979, and the headline in the Oct 22 edition of The Straits Times was “Hi there, Mac!”.

ST PHOTO: HAIRIS

SINGAPORE - Singapore’s gleaming skyscrapers, handful of world-class tourist attractions, and relentless efficiency make it an easy place for doing business and to visit on holiday.

What gives the city soul, however, is its hopping food and bar scene. The Straits Times has played an outsized role in shaping the Singapore food landscape. After all, it has had to answer to, and exceed the expectations of, a nation of opinionated foodies.

Russian Dressing and Sunshine Cocktail

What did people in Singapore eat in 1845, when the paper made its debut? The Straits Times provides some clues, not in features or reviews, but in advertisements.

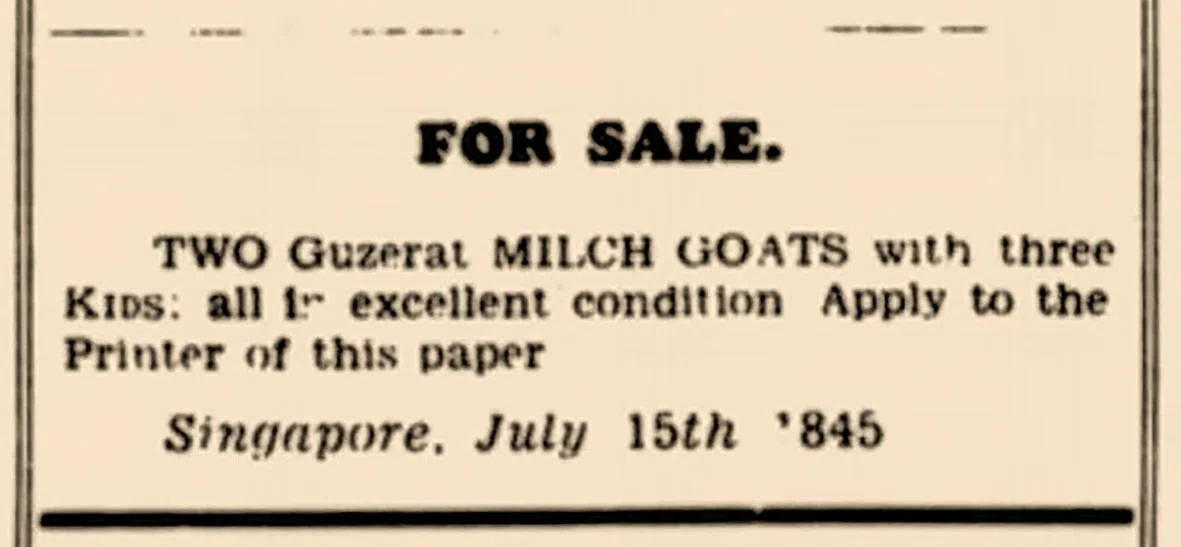

On the front page of the first edition, July 15, 1845, is a tiny ad that reads: “FOR SALE. Two Guzerat milch goats with three kids: all in excellent condition. Apply to the printer of this paper.”

Goat milk, it would seem, featured in the diet at the time. On Nov 4 that year, J.Mann & Co, “wholesale and retail provisioners”, located at No. 23 Kling Street, announces it has received shipments of a long list of food and drink. The goodies for sale include Wyatt & Co’s English pickles, Finest Durham Mustard, Tart Fruits in Fine condition and Prime Wiltshire Bacon.

Milk goats for sale on the front page of the first edition of The Straits Times and Singapore Journal of Commerce on July 15, 1845.

PHOTO: ST FILE

Food, if it is mentioned at all, is in a news or business context, with purveyors taking ads listing what they have to sell, and the paper tracking the prices of fish, vegetables and other food products.

It is only in the 1930s that the first recipes appear. By this time, the paper has women’s pages, focusing mostly on fashion and make-up.

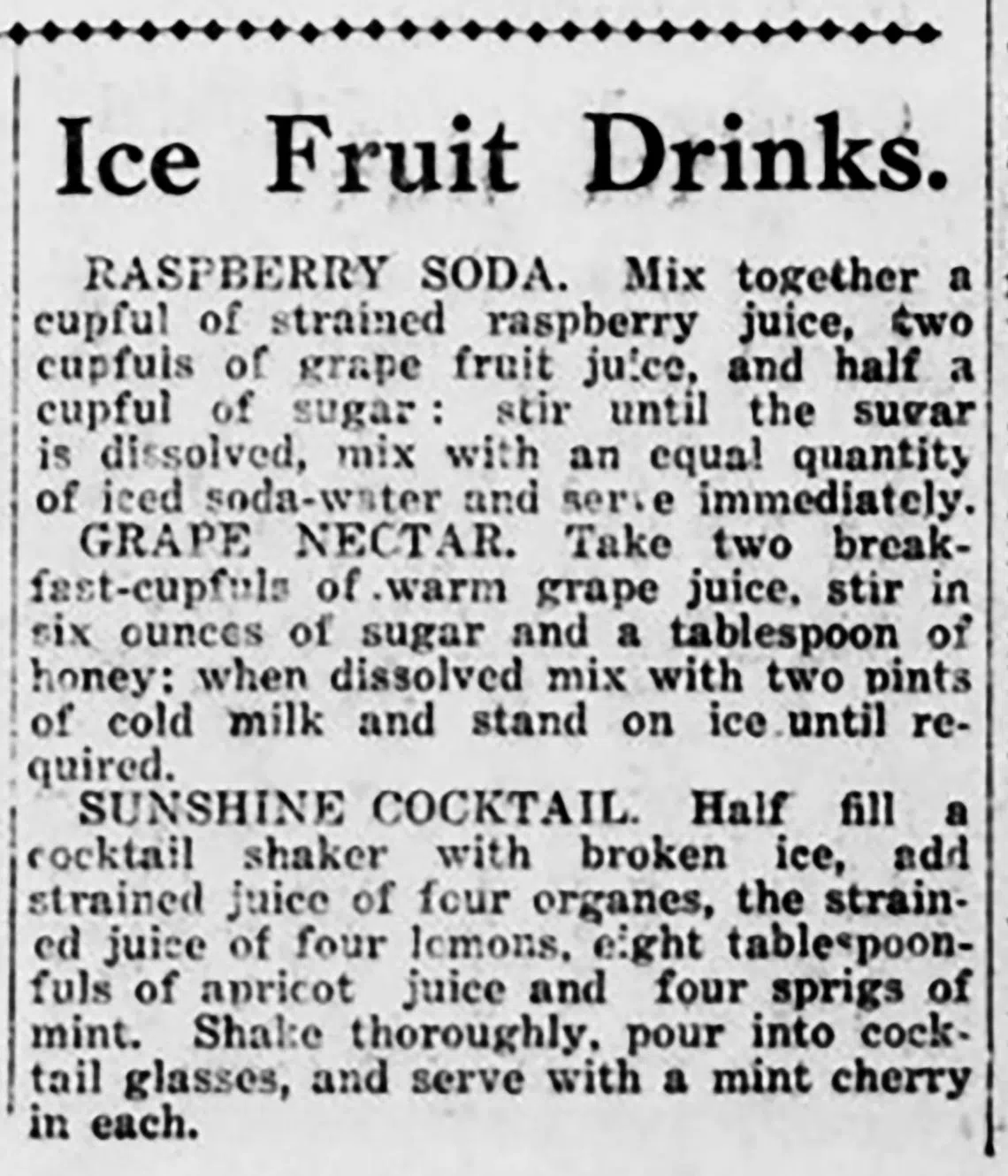

The Sept 26, 1931, edition carries, at the bottom of a page dominated by a story about “Bustles without the whalebones”, recipes for Ice Fruit Drinks – Raspberry Soda; Grape Nectar, which calls for “two breakfast cups of warm grape juice”; and Sunshine Cocktail, made with “organes” (presumably oranges), lemon and apricot juices, and mint.

The Sept 26, 1931, edition carries recipes for Ice Fruit Drinks – Raspberry Soda, Grape Nectar and Sunshine Cocktail.

PHOTO: ST FILE

This pretty much characterises food writing from the 1930s to the 1960s. Recipes are spotty, usually British or French. On Nov 10, 1940, below a story listing cosmetics king Max Factor’s beauty tips, are recipes for Russian Dressing, Olive Sauce and Tomato Salad.

In the first half of the 1970s, with the women’s liberation movement that began in the late 1960s prompting more women to join the workforce, tensions in the kitchen reverberate in the food writing of that time. Some of this is captured in her Sunday column, Adventure in Food, by one Mary Kogan. On April 27, 1975, she tells the story of her outraged friend, a working woman, who has put a sign in her kitchen saying: “The opinions expressed by the husband in this house are not necessarily those of the management.” She will only take it down when her husband agrees to help out in the kitchen.

“...it does reflect the fact that woman’s (sic) grievances are at least beginning to be taken seriously, and with new-found understanding”, is Ms Kogan’s rather optimistic view of the tension that still exists today.

Shaping Singapore’s foodie culture

Foodies perusing the Sunday food pages from the late 1970s through to the early 2000s will see how much the paper has shaped their approach to and appreciation for food. It is a time of discovery and learning, for both writers and readers.

After decades of treating food as a good-to-have at best and an afterthought at worst, The Straits Times starts getting serious about food in the late 1970s. Those European-centric recipes make way for Asian ones. Food journalism and restaurant reviewing become viable careers.

The British journalists and editors who had run the paper make way for local staff, who edit the paper differently. Food writing takes on a distinctly Singaporean flavour.

Instead of being preoccupied with what is happening in Europe, the focus moves to Singapore and Asia. When Japanese department store Yaohan opens its first store at Plaza Singapura on Sept 14, 1974, and its second in Katong on Aug 28, 1977, there are stories about its innovations. These include produce weighing machines that dispense stickers with the prices on them, and the soft Japanese-style bread – including the popular an pan that customers queue hours for – that has become ubiquitous in Singapore.

A Japanese food fair at Yaohan at Plaza Singapura in 1980. Yaohan opened its first outlet in Singapore at the mall on Sept 14, 1974.

ST PHOTO: CHUA PENG TEE

When fast-food chain McDonald’s opens at Liat Towers in October 1979, the headline in the Oct 22 edition of The Straits Times Section 2 is “Hi there, Mac!”. The story, by one Anita Evans, has a picture of customers in bell-bottoms queueing up to order the burgers and fries that are part of the “experience”.

“Hawker stalls were never like this. In McDonald’s, a uniformed phalanx of teenage serving ‘crews’ produce uniform food of a uniform taste, colour and size by means of highly sophisticated computerised cooking machinery,” Evans reports.

It is on July 29, 1979, that food writer Violet Oon makes her debut in The Sunday Times’ Timescope, with a two-parter about eating in Thailand.

In her weekly Pot Luck columns, she writes about eating in the Philippines, London and France, and also covers substantial ground in Singapore. Hawker food, posh food, ultra-luxe food, she offers a smorgasbord for readers to learn from.

For years, former journalist Violet Oon was the most famous food writer in Singapore. After she stopped writing for ST, she went on to be a food consultant, and is now a restaurateur, with her Violet Oon Singapore brand.

PHOTO: COURTESY OF VIOLET OON

At around the same time, another food writer rises to prominence at the paper – Ms Margaret Chan, whose food reviews also run the gamut of high, low and in between.

Alongside them are journalists such as fashion writer Lim Phay-Ling, who through the 1980s and 1990s would also write about food. These include a multi-page feature about Singapore kopi culture.

Lifestyle writer Lee Geok Boi’s recipes reflect the way Singaporeans eat – multiculturally, unencumbered by borders, and back then, with no concern about cholesterol levels.

On July 16, 1989, she gives recipes for offal dishes – Dou Miao With Intestines, and Braised Tongue With Potatoes and Chicken Liver With Spinach Fettuccine, a trio that spans East and West. On Oct 28, 1990, she writes about using the right cuts of meat for classic dishes, with recipes for Pork Chops With Tomatoes, Pot Roast Beef and Sloppy Joes.

Her intricate recipes come with few photographs, unheard of today. Readers want to see the finished product, at least, before committing time, money and effort into cooking and baking.

In 1994, Ms Sylvia Tan, then an editor in the news section of the paper, starts writing her cooking column, Mad About Food. Her recipes, drawn from her travels and Peranakan heritage, resonate with readers despite having no photographs, only illustrations. For a new generation of budding cooks, her simplified Peranakan recipes are approachable, and written without the weight of a Nonya matriarch’s expectations.

From the 1980s, to reflect the population’s aspirations, the paper has weekly columns about wine and other alcoholic drinks, helmed at various times by the likes of well-known wine experts such as Mr Ch’ng Poh Tiong, Dr N.K. Yong and Mr Edwin Soon.

Buffets to omakase

If the late 1970s mark the first peak of the paper’s food coverage, then the paper hits peak food again on Sept 28, 2003, when the new look Sunday Times, with a new masthead and Lifestyle section, renamed from Life!, debuts.

The Taste pages offer a buffet of stories – on disappearing foods like ah balling, sugee cake and lei cha fan and where to eat them; the increasing appetite for what is at the time exotic vegetables, including romaine lettuce, Truss tomatoes, portobello mushrooms and red radishes; and eateries selling bull, turtle and crocodile penis soups. Food features are also making it onto the Lifestyle cover.

In the mid-2000s, with another revamp of The Sunday Times, there is even more food content.

Feature stories cover the full taste spectrum. There are stories about healthier hawker food; old-school hawker food; grumpy hawkers; the multiple waves of bubble tea, Korean restaurants and hotpot restaurants; the rise of the home barista; primers on luxe food such as white truffles; inexpensive food in the Central Business District; the rise, and subsequent fall, of supermarket sushi; the rise and rise of high-end sushi; the growing appetite for tasting menus and omakase meals in restaurants; the obsession with Japanese beef; food fads – salted egg yolk croissants, rainbow cakes, and sourdough bread; among other things.

Knowing what makes a Singaporean’s heart beat faster, the paper comes out with Love Mee on April 15, 2007, a feature about instant noodles. It features 50 recipes from chefs and its food writers for how to cook this Singapore favourite creatively. It is later published as an e-book.

On April 15, 2007, the paper published a feature on instant noodles. Chefs and the paper’s food writers offered creative recipes on cooking the noodles. Straits Times Press later published this as a book, Cook Mee.

PHOTO: STRAITS TIMES PRESS

New columns come thick and fast. There is Singapore Cooks, featuring recipes by readers. Foodie Confidential, continuing on from the 2003 revamp, branches out to also feature chefs and bartenders.

Other columns continue the mission of decoding food for readers. There is Cheat Sheet, offering primers on topics such as different varieties of bananas, durians, peppercorns and olives. Eater’s Digest has writers taking turns to review cookbooks, cooking from them so readers know what books to buy or avoid.

Reviews continue, with Mr Wong Ah Yoke anchoring the main restaurant review; several writers taking turns to unearth budget eats for Cheap & Good; and for a spell, Zi Char Review for belt-tightening times and Posh Nosh, a snack recommendation column, both helmed by this writer.

The OG food influencers

In American gang and later rap parlance, OG or Original Gangster describes a “highly respected originator”. Before the flood of people self-identifying as food influencers, there are Violet Oon, Margaret Chan and Wong Ah Yoke.

At the height of their power, they could make or break a restaurant or hawker stall, whether they want to admit it or not. Readers would turn up at the places they review, toting newspaper cuttings and ordering exactly the dishes they praise.

Ironically, they hone their craft elsewhere before joining The Straits Times. Ms Oon gets her start at New Nation and The Singapore Monitor; Ms Chan at New Nation; and Mr Wong at The Singapore Monitor and in magazines.

Ms Oon, 76, now a restaurateur, falls into food reviewing in the 1970s for New Nation, quite by accident.

She says that at the time, with expatriate staff at the papers leaving their jobs, Singaporeans take over as editors. The paper’s Eating Out column had been helmed by New Zealand-born Wendy Hutton, and she takes over it in 1974.

There is some fanfare when Ms Oon debuts in The Sunday Times, with the paper announcing her arrival this way: “Starting today, Singapore’s favourite food writer in The Sunday Times...”

Mr Wong joins The Straits Times as a sub-editor in 1992, and becomes part of a group formed in the early 1990s to review restaurants. They use the nom de plume, Mah Kan Keng, an approximation of Makan King. The reporters take turns to write the reviews, incorporating views from the others at the meal. Anonymity and tasting in a group would ensure fairness. Hilarity ensues when readers write in to Mr Mah, Madam Mah, Ms Mah and “Dear Kan Keng”.

The column hums along until, as Mr Wong, 64, puts it: “The other writers had to do this on top of their other work and they dropped out one by one until I was the only one left.”

Even then, he continues writing under Mah Kan Keng. It is not until March 29, 1998, that he has his first review printed with his byline, for a weekly column called Eats. His tenure as the food critic of The Straits Times continues until he retires in 2023.

Straits Times restaurant critic and food writer Wong Ah Yoke with a framed copy of a customised Life cover when he retired in 2023 after 31 years with the paper.

ST PHOTO: WANG HUI FEN

Anonymity is not an issue with Cheap & Good, the other review column helmed by writer Teo Pau Lin for about a decade from 1995, and then by a series of writers from around the newsroom. She scours Singapore for egg tarts, laksa, rojak, vadai and Thai-style beef noodles, among other things.

Ms Teo, 54, who leaves the paper in 2010 to start a cake business, says of her reviews: “It always resulted in dramatic increases in business for the hawkers. The queues would be super long for at least a week or two. The hawkers would be overwhelmed and overworked, and I always made sure to warn them beforehand to get more manpower on the day the story comes out.”

What accounts for the raging interest in food?

“It is an instant buy-in to sophistication,” Ms Oon says. “To become sophisticated about art or dance would take years of study. But with food, anybody could be sophisticated. Every cabby can tell you where the best places are for steamed fish. A Prada bag costs $4,000. A prata is $2.”

Ms Oon and Mr Wong say their training as reporters helps them in the early days. They widen and deepen their own knowledge about food in tandem with readers. Those early reviews, they say, are more reportage than critique.

“In those days, chefs would take you into the kitchen and show you things,” Mr Wong says. “That’s how I learnt. You never pretend you know something when you don’t. The voice came later.”

Both demur when asked if they can “break” a restaurant.

Mr Wong says: “I wouldn’t say that. I can affect their business a little, but not enough to shut them down.”

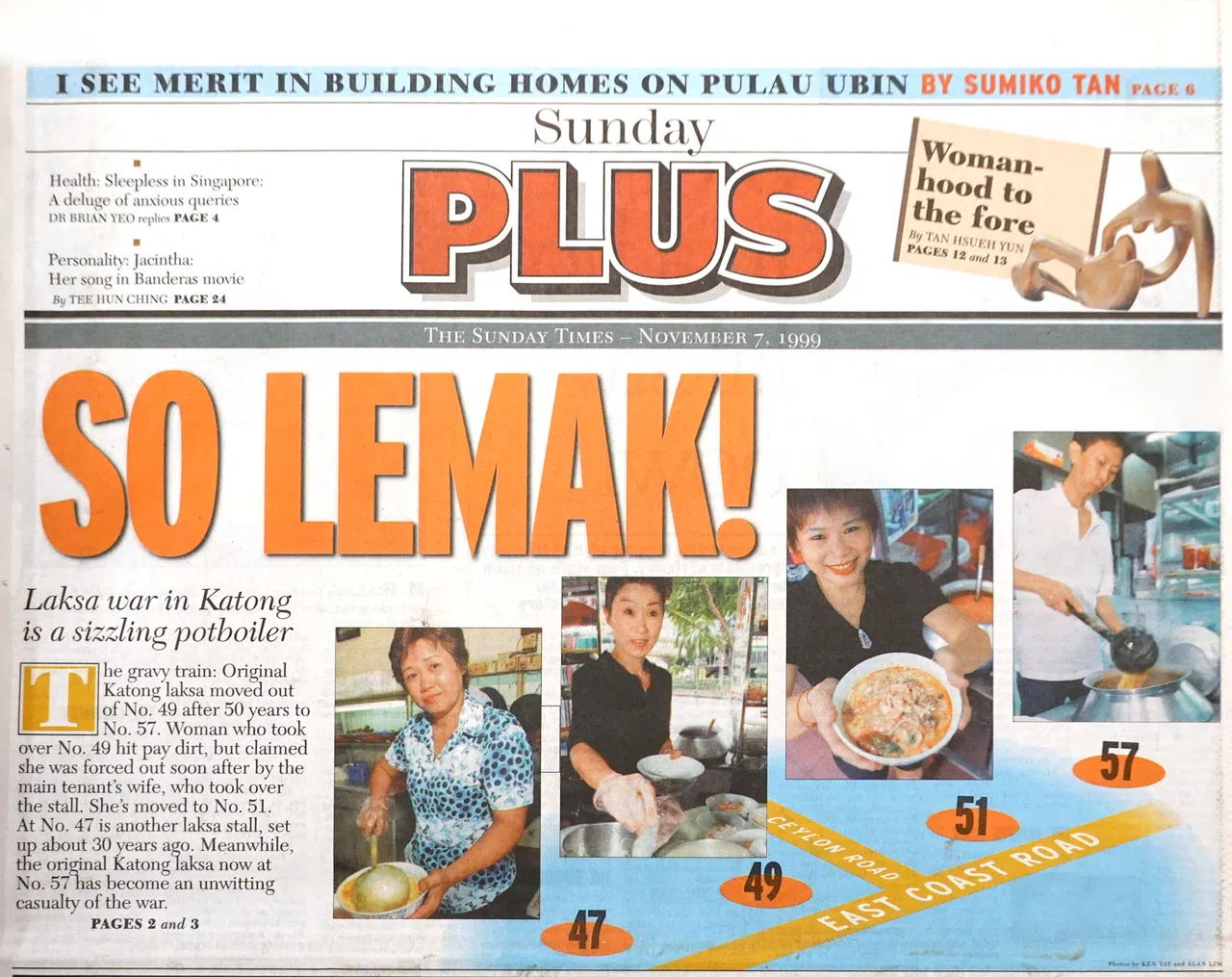

But a bad review can have consequences, as the Katong laksa war of 1999 shows. The Sunday Plus cover story on Nov 7 by reporter Lea Wee is about four stalls in Katong claiming to serve the original version of the dish. Ms Oon, a food consultant at the time, tries all four versions and gives Original Katong Laksa, at the corner of Ceylon and East Coast roads, the best score.

The Sunday Times’ feature on Nov 7, 1999, about the laksa war in Katong.

PHOTO: ST FILE

Fast forward to the next Sunday, Nov 14. In a follow-up, reporter Karl Ho reports that business at two of the stalls Ms Oon pans is badly affected. One of the stallholders regrets talking to the paper. “I beg you, tolong, tolong,” she pleads. “Please don’t write anything about me and my stall any more.”

Today, it is commonplace for chefs and restaurant owners to talk about their craft in the media. Back then, it is not. The work of these, and other food writers in the paper, help to raise the profile of hawkers, chefs and restaurateurs in Singapore, making stars out of some of them.

On May 8, 2005, Mr Wong’s review is on Pu Tien, a restaurant in Kitchener Road serving Hing Hwa cuisine, from a small dialect group in Fujian. Cue stampedes to the restaurant for its homespun food.

Mr Fong Chi Chung, 56, is the owner and he now presides over the Putien empire, with more than 100 restaurants, in Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, China, Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan. There are 17 in Singapore alone.

He says: “I didn’t know who Ah Yoke was back then. I wasn’t English-educated so I didn’t read English newspapers. The article about Putien was published around Mother’s Day that year. Wow, the moment the article was out, the restaurant was suddenly packed! There was a huge crowd lining up outside the restaurant, and I was a bit shocked when I saw it.”

Another discovery is Artichoke, a five-month-old Middle Eastern restaurant at Sculpture Square when Mr Wong reviews on Jan 23, 2011. It is now at New Bahru in Kim Yam Road.

“Business wasn’t great. I could see my bank account dwindling, and we had maybe a runway of four, five months to tahan or close in under a year,” says owner Bjorn Shen, 42, using the Malay word for endure.

He says the restaurant starts getting calls from people wanting reservations when the review comes out.

“The snowball started rolling from that day onwards,” he adds. “It gave more people the chance to try our food. Most people liked the food, and that gave us the confidence to continue doing what we were doing.”

Everybody’s a food critic

Anyone with a smartphone and an Instagram account can be a food critic now. Restaurant publicists invite them to media events and tastings, alongside legacy media. The publicists hand out “tasting notes” of the meals, to make it easy for influencers to put together content.

The Straits Times food writer today has a lot more competition. But she has all the tools that influencers have – smartphones, social media accounts, name recognition; and some that they do not – hard-driving bosses who question facts and story angles, and demand sharper reporting; newsmakers who flag errors or retaliate against unflattering copy; readers who hold them to a higher standard than they do influencers, and who have no qualms about calling out lax reporting or bad judgment.

Food writer Cherie Lok, 27, a January 2024 hire, says: “I’ve come to realise that our responsibilities are manifold. We need to track industry news, illuminate issues, highlight key personalities, entertain with punchy, vivid writing, and tell people what’s worth eating.

“That last bit is particularly hard to do in an era where everyone has an opinion on food and a platform through which to broadcast it. The kind of trust that readers place in veteran writers like Ah Yoke isn’t easily earned and can only be built up with time.”

Ms Eunice Quek, 38, social media editor at Life, is tasked with growing ST Food’s social media accounts. The one on Facebook has 61,000 followers, and the one on Instagram has 24,000. She has been a food writer since joining in 2009, and remembers the food writer pep talk.

“Responsibility to readers, to always try to approach a story from the consumer’s point of view,” she says. “To cover all ground. Legwork is of the utmost importance. Where possible, taste the food that we write about, visit the locations to have a sense of place.”

She starts reviewing for Cheap & Good in 2011. “It was very exciting for me but I also knew that with great power comes great responsibility,” she says. “I became a lot more mindful and careful with what I wrote, as it was a reflection of myself, and could make an impact on the businesses.”

This is something she hews to when it comes to her social media strategy.

“Featuring food first, nothing too clickbaity,” she says. “The posts must be a fair representation of the stories everyone writes. Everything is ‘very ST’. But I do try to have some fun with captions and photos while remaining ‘very ST’.”

That sense of responsibility food writers never shrug off stands them in good stead.

Putien’s Mr Fong says: “I believe that credible media figures are trustworthy, so I don’t think their influence has diminished. Their credibility is built from years of accumulated expertise and unique writing skills that enable them to write engaging stories and gain loyal readers.”

The next course

The launch of the Singapore Michelin Guide in 2016; the multiple waves of celebrity chefs from overseas opening restaurants here; the rise of the Singaporean chef, food fads, food feuds; the rise of private dining businesses; the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on restaurants – the work of pointing readers in the direction of good food, of showing them the length and breadth of the food scene here, continues.

Through the years, a clear pattern emerges. Food trends, peaks and troughs, they happen in cycles.

The food scene has had one of its worst years in 2024, with diners deserting restaurants, preferring to save their strong Singapore dollars on post-Covid wanderlust. Of course, it has happened before.

In the Feb 1, 1998, edition, in the thick of the Asian financial crisis that began in 1997, Sunday Plus runs a story about how fine-dining restaurants have been hit. It lists a number of such restaurants that have shuttered, and how the ones still open are lowering their prices. That story sounds eerily like the ones in the paper in 2024.

The story quotes chef Justin Quek, then managing director of Les Amis, saying: “Our New Year’s Eve menu last year was priced at $265. In 1994, we charged $1,000. We can’t do that any more. We want to be friendly to the market.”

That strategy still works today.

Chef Joel Ong, 37, co-owner of Enjoy Eating House, a casual restaurant in Stevens Road, says: “If we provide good value to our customers, there is a higher chance of them returning or recommending us to their social circle.”

What he says applies to food coverage in The Straits Times.

Value is a loaded word. For some, a fast-food meal represents good value – burger, fries and a milkshake – served fast and efficiently. Food coverage can be that way. In its history though, The Straits Times has chosen another route. Call it the hawker route. It is not uniform and consistent in taste, colour and size. Instead, it is many-splendoured in its variety, and in its ability to adapt and change to suit the circumstances of the day, to meet the expectations of its readers. That is how it has been able to appeal to the soul of a nation obsessed about food.

In good times and bad, through lean years and fat, people gotta eat. In good times and bad, through lean years and fat, The Straits Times shows them how, where and why.

Tan Hsueh Yun joined The Straits Times in 1991 and is senior food correspondent. She covers all aspects of the food and beverage scene in Singapore and believes food is Singapore’s ultimate soft power.

Recipe: Garden Focaccia

When making Garden Focaccia, large pieces of vegetables work better than fiddly slices.

PHOTO: ST FILE

Ingredients:

250g plain flour

1 tsp salt

1 tsp instant yeast

2 Tbs extra virgin olive oil, plus more for greasing and brushing

175ml lukewarm water

Vegetables

Coarse sea salt

Method:

Place the flour, salt and instant yeast in the bowl of a food processor. Cover and pulse two or three times to mix the dry ingredients. Add the oil and water. Pulse 14 to 16 times, until a ball of dough forms. To do this by hand, whisk the flour, salt and instant yeast to combine in a large mixing bowl. Make a well in the centre, pour in the water and olive oil, and mix with a large spoon until a sticky dough forms.

Lightly flour your hands and shape the dough into a ball. Coat the inside of a mixing bowl with olive oil. Place the ball of dough in it, smearing the bottom with the oil in the bowl. Flip the ball over. Cover with plastic wrap or a tea towel and let it sit until it has doubled in size. This will take two to three hours, depending on the weather and how active your yeast is.

When the dough has doubled in size, punch it down in the bowl. Grease a 20cm square or round cake tin, or a 23cm enamelled cast iron pan, with olive oil. Transfer the dough to the pan and stretch it so that it reaches the edge of the pan. Or line a baking sheet with baking paper, place the dough on top and shape it however you want. The dough should be about 1cm thick. Cover with plastic wrap or a paper towel and let it rise for 40 minutes.

Wash, dry and slice the vegetables with which you intend to decorate the focaccia. Coat with olive oil and set aside. Preheat the oven to 230 deg C.

After 40 minutes, brush the top of the dough with olive oil. Sprinkle on the coarse sea salt. Decorate the focaccia, pressing the vegetables onto the dough. When done, you can brush the entire top of the focaccia with more olive oil, or leave it be.

Place in the oven and immediately turn the temperature down to 200 deg C. Bake for 35 to 40 minutes or until the focaccia is light golden brown. Remove from the oven and cool 15 to 20 minutes before serving.

Serves four.