COVID-19 SPECIAL

Rethinking dorms: Next steps for foreign worker housing in Singapore

New safety rules could shake up how dorms are run, and also result in consolidation

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

S11 Dormitory @ Punggol has Singapore's largest cluster, with more than 2,600 cases of Covid-19.

ST PHOTO: MARK CHEONG

In late January, when much of Singapore was in the Chinese New Year mood, Mr Neil Yong was busy with a flurry of meetings.

Singapore had confirmed its first case of Covid-19 on Jan 23, and Mr Yong, an executive director of local construction giant Woh Hup, was watching with concern how the coronavirus was spreading elsewhere.

The privately held company, which built landmarks like Jewel Changi Airport, has 2,000 foreign workers staying in the four dormitories it runs. A further 1,700 workers stay in externally run dorms.

A crisis management team was set up, led by Mr Yong, and a first meeting was held on Jan 27.

"We immediately identified that the spread of Covid-19 among workers would pose the greatest threat to us, due to the quantity and proximity of workers intermingling at sites and dormitories," he was to recount later.

A plan was executed.

All its worksites suspended work for two days and workers were told to remain in their rooms.

One of its dormitories - the 372-bed SK2 Dormitory in Sungei Kadut - was designated a central isolation facility. Rooms there were partitioned and equipped with features like electrical sockets.

All workers were screened during those two days before returning to work.

The company implemented its own contact-tracing plan and developed detailed schedules to segregate workers by floors.

On April 8 - weeks after its measures were put in place - Woh Hup saw its first two cases of Covid-19.

Buy-in and compliance from the workers were not easy, Mr Yong said, but the exponential growth potential of Covid-19 meant it was safer to err on the side of caution as soon as the first cases were detected.

"We have a very small window for missteps thereafter, before it becomes uncontrollable for us," he wrote in a widely shared note on April 10 that would prove prescient.

As of April 27, 12 of its workers tested positive for the virus. Woh Hup declined to comment on its current case numbers.

DORMITORIES IN THE SPOTLIGHT

Singapore had its first foreign worker Covid-19 cluster in February, when five infected Bangladeshi workers were linked to a worksite in Seletar Aerospace Heights.

On March 30, the Ministry of Health announced that a cluster had formed at S11 Dormitory @ Punggol at 2 Seletar North Link. It has since become Singapore's largest cluster, with more than 2,600 cases. From April through May, more workers in other dorms and worksites became infected.

By April 18, there were 4,446 work permit holders confirmed with Covid-19. By May 1, the number had grown to more than 15,000.

As of Sunday, the figure stands at more than 29,000, partly a result of active testing at dormitories. Singapore's total number of cases, which includes patients in the wider community, is 31,960.

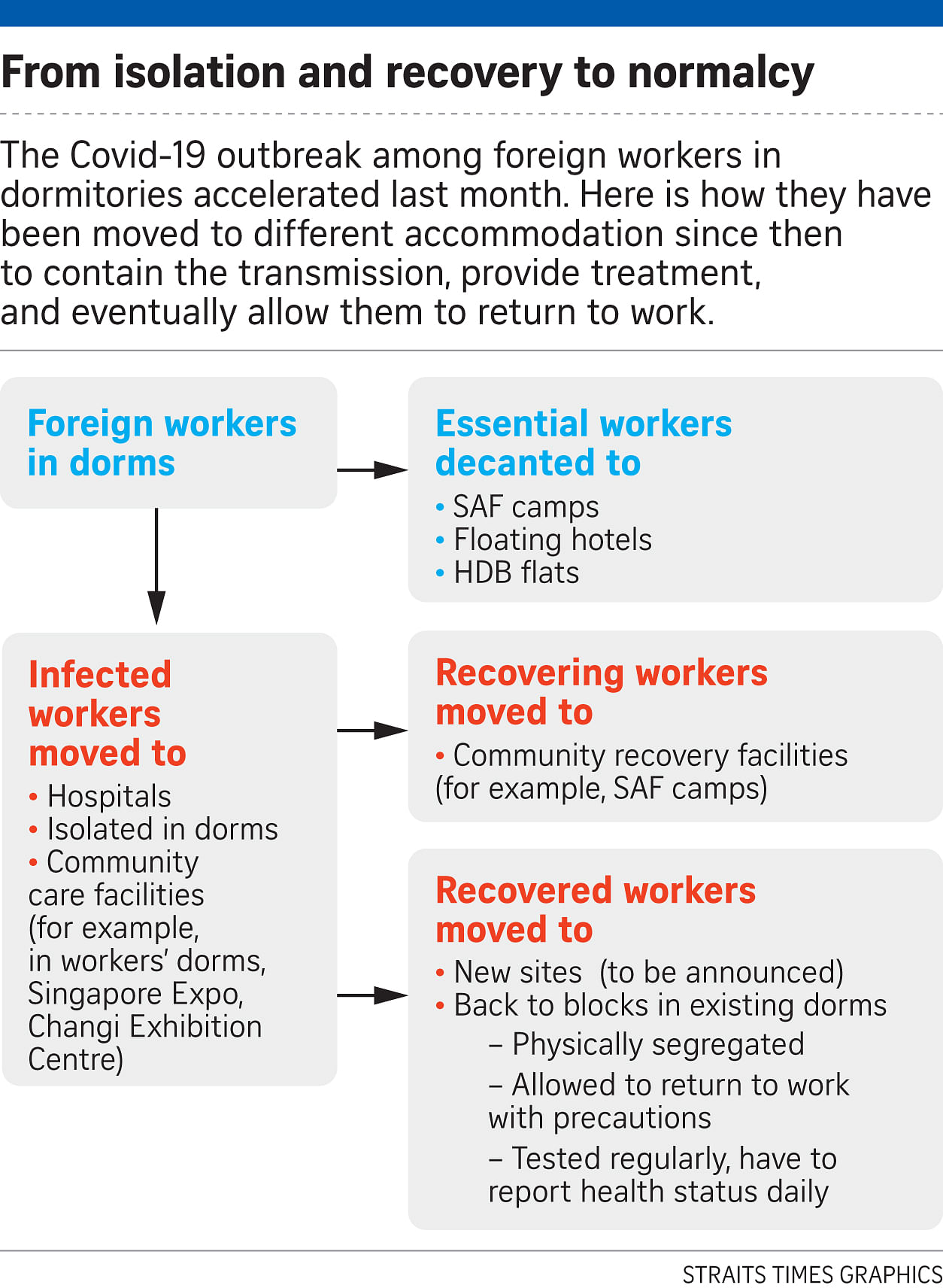

On April 7, the Government set up a task force to manage the outbreak in dorms. It has worked out a detailed system that includes testing, isolation, hospitalisation, recovery and spreading out of workers to facilities like Singapore Expo.

The outbreak has put the spotlight on Singapore's 323,000 foreign workers staying in dorms, and how the crowded conditions there led to the virus' spread.

Of the 720,800 work permit holders - excluding domestic helpers - in Singapore, 287,800 are construction workers, and the rest work in areas such as marine, processing and the service sectors.

There are three types of dorms.

About 200,000 workers stay in 43 purpose-built dormitories (PBDs). These are compounds in far-flung corners of the island, with amenities such as minimarts and gyms. Their capacity can range from a few thousand beds to 25,000 beds.

The big PBD operators include listed company Centurion Corporation. Others are mainly private companies such as Vobis, a subsidiary of Aik Chuan Construction, which runs three PBDs.

The second type of housing is factory-converted dormitories, numbering about 1,200 and run mainly by employers or operators.

These are industrial buildings or warehouses partially converted into dormitories. They house 95,000 workers.

A third type is on-site housing, including temporary quarters at construction sites. They house about 20,000 workers.

DORMS DESIGNED TO SPECS

Dorm operators have been on the receiving end of much of the public's criticisms, but they say this is misdirected.

Centurion chief executive Kong Chee Min pointed out that its Westlite dormitories, totalling 28,000 beds, were "designed to meet regulatory requirements in normal times and were deemed entirely appropriate in those times".

They come with stipulated sick bays, isolation wards and quarantine plans in the event of an outbreak.

Migrant Workers' Centre chairman Yeo Guat Kwang said such stipulations were the result of lessons learnt from dealing with the severe acute respiratory syndrome (Sars) outbreak in 2003 and H1N1 in 2009.

But "nothing was the same for the coronavirus", he added.

While H1N1 infected many people, "it was a case of you-catch-it-you-feel-it, that's why you just needed to have a sick bay to quickly isolate cases", Mr Yeo said.

"With Covid-19, there are often no symptoms, and the precautions were built for a situation where someone can be isolated straightaway when you see symptoms."

S11 Dormitories managing director Johnathan Cheah said "norms that have worked well in peace time have certainly been challenged".

EARLY WARNINGS

Dorm operators said they began implementing enhanced safety measures as early as January, following guidance from the Ministry of Manpower (MOM).

In e-mails seen by The Straits Times, MOM sent operators near-daily updates and advisories, including a directive on Jan 28 to set up 36 quarantine beds or two quarantine rooms, whichever had more beds, by the next day.

Additional requirements were issued when the crisis alert level was raised to orange on Feb 7. Directives to step up precautions were also issued on April 1 after the cluster at S11 was detected.

On hygiene in dorms, Mr Cheah, who is also president of the Dormitory Association of Singapore, said the reality has been distorted by inaccurate information on social media.

"The dorms in Singapore are governed by better legislation than that in many countries with a migrant worker population," he said.

Another issue of concern has been why public funds are being used for the lockdown operations when dorm operators have healthy bottom lines.

For the 2019 financial year, the net profits of Centurion, Wee Hur and Lian Beng from their dormitory and other businesses averaged over $35 million.

But, according to Mr Cheah, the bulk of dorm operators have been struggling in the last few years due to lower-than-projected occupancy, payment delinquency and bad debts.

Operating expenses have gone up significantly since Covid-19 with, among other things, additional utility, cleaning and sanitation bills.

Since last month, dorm operators have been working with the authorities in areas such as food distribution and medical support.

Centurion said in an earlier response that it will absorb the costs for measures it initiated, such as distributing free disinfectants and developing new technology for temperature logging and grocery ordering.

SAFER DORMS

The dense nature of dormitory living has been acknowledged by the Government and epidemiologists as one key reason the virus spread so easily.

Beyond the dormitory setting, worksites and popular rest day destinations like Mustafa Centre mall contributed to the spread.

Features of communal living remain a key principle for foreign worker housing post-Covid-19, MOM told The Straits Times.

Dormitories allow migrant workers to be in the company of friends, cooking, eating, relaxing and praying together, said Mr Kevin Teoh, MOM's divisional director for foreign manpower management.

"We will have to thoroughly examine how their social and emotional needs can continue to be met while more safe distancing measures are being introduced," he said.

Observers say much can be done within the existing dormitory framework, particularly in living density.

Under current guidelines, the minimum living space for each dorm resident is 4.5 sq m, which includes sleeping space, kitchen, dining and toilet areas. This means 12 to 20 residents typically share a room crammed with bunk beds.

This is similar to having 20 adults living in a four-room HDB flat, said Dr Harvey Neo, programme head at the Lee Kuan Yew Centre for Innovative Cities at the Singapore University of Technology and Design.

That is too small and has a serious and direct impact on accelerating the spread of viruses, he added.

Others, such as non-governmental (NGO) organisation Transient Workers Count Too, have called for smaller, self-contained apartments with their own toilets and kitchens, with windows on facing sides for cross-ventilation.

Land use can be intensified to allow for this, said Dr Sing Tien Foo, director of the Institute of Real Estate and Urban Studies at the National University of Singapore (NUS).

GOING HIGH-RISE?

But this would require the authorities to review current building guidelines for dorms, such as increasing the gross plot ratio, which limits, among other things, building heights.

Allowing longer lease terms and smaller land plots may attract developers of various sizes to compete and craft different housing models, instead of the current model that is skewed towards bigger operators, added Dr Sing.

But he noted that high-rise dorms will increase construction costs, and compliance with fire safety requirements will be more stringent.

Current dorms typically have lease terms of between nine and 30 years. "Developers will only invest more in building more permanent structures to support migrant workers if they are given a longer lease term on the land," he said.

MOM's Mr Teoh said the ministry has committed to reducing dorm density to facilitate safe distancing.

Beyond rooming arrangements, it is looking into adjusting the design and usage of common facilities such as kitchens, toilets and recreation hubs, he said.

SIGNS OF THINGS TO COME

But these changes will take time, given the challenges in finding suitable sites to house new dormitories, and spare capacity to house residents while renovations take place to upgrade existing dorms, Mr Teoh added.

While PBDs are typically located within industrial areas, the locations of these short-and medium-term housing could vary.

But observers say this also depends on Singaporeans' level of acceptance of having foreign workers in the community.

NUS sociologist Tan Ern Ser said the large numbers of workers being infected with Covid-19 may have evoked some feelings of regret among Singaporeans.

"But I'm not sure if the situation has necessarily helped us overcome the Nimby syndrome present in some quarters," he added, referring to "not in my backyard" sentiments.

While MOM did not comment on questions about tightening of regulatory requirements for dorm licences or possible changes to dorms' business models, safe management guidelines for the construction sector announced this month provide some clues.

Among the conditions for construction work to resume from June 2 is a strict ban on workers from different dorms intermixing at, or being cross-deployed to, different worksites.

Dorm operators will have to install barriers to prevent workers from different blocks from mixing, assign showers and stoves to those staying in the same room, and schedule the use of communal facilities.

If made perpetual, these rules will not only shake up how dorms are run, but could also result in consolidation for an industry hit by a soft construction sector whose recovery Covid-19 has thrown into doubt.

THE BOTTOM LINE CHALLENGE

Operators like Mr Cheah said they are prepared to work with the Government to implement changes based on the lessons wrought by Covid-19. But many such changes will entail higher costs, they added.

Experts said the tripod of Government, dorm operators and employers should share the costs of these improvements - but so should Singaporeans, who today indirectly benefit from low-wage foreign labour.

This is because any cost increase in dorm operations will necessarily impact construction costs and translate to higher building costs, said NUS Department of Building Associate Professor Daniel Wong.

One way to improve both efficiency and accountability in the dorm model is to adopt a government contracting model, said Nominated MP and Singapore University of Social Sciences economist Walter Theseira.

Under this model, dorms would be treated as a utility service that the Government is responsible for, with operations contracted out on a tender basis to private operators and reviewed frequently.

This would reduce operators' policy risk exposure to the Government changing how many foreign workers are allowed in, "likely reducing costs and excess profits because pricing and revenue or risk-sharing can become tender parameters", he said.

Government agencies like the Housing Board, with its experience in public housing, could also be involved in the management of dorms, said Professor Foo Maw Der of the Nanyang Business School.

A hybrid model with some dorms managed by private enterprises and others by government-related organisations could also facilitate new operation methods being tried out, he said.

SHARING THE COSTS

NGOs agreed that dorm improvement costs should be borne collectively by various stakeholders.

Mr Michael Cheah, executive director of NGO HealthServe, suggested that part of the foreign worker levies collected by the Government be used to support the changes.

The Humanitarian Organisation for Migration Economics said responsibility should also go up the food chain to main contractors and shipyards, as these bigger stakeholders have greater clout to ensure standards are adhered to.

On the flip side, dorm operators who pack in workers in excess of the regulations should be penalised by being made to disgorge profits gained from the overcrowding, on top of existing penalties, it said.

Observers said future dorms have to meet the needs of workers and be a space they can call home.

Nanyang Technological University School of Social Sciences Assistant Professor Laavanya Kathiravelu said one option is to form management committees within dorms, not unlike those in condos.

"Some dorms have dorm ambassadors, but those are not elected positions but usually appointed ones," she said.

For Woh Hup's Mr Yong, Covid-19 has been a wake-up call on the importance of being adaptable in these uncertain times and learning to live with safe management protocols in place, while managing one's business effectively.

The firm took steps early, but as Mr Yong said in his April 10 note: "The sad truth is, we will never know if we have done too much, we will only know if we have done too little."

• Additional reporting by Choo Yun Ting, Lim Min Zhang, Joanna Seow, Olivia Ho, Aw Cheng Wei, Michelle Ng and Tan Tam Mei