Push to expand residential schemes, social support to help people with disabilities thrive

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Mr Neo Boon Hao has been living with a housemate in an Ang Mo Kio flat since 2022.

PHOTO: AUTISM RESOURCE CENTRE (SINGAPORE)

SINGAPORE – A two-room flat in Ang Mo Kio has been home to Mr Neo Boon Hao, a 26-year-old with autism, since mid-2022. The cafe assistant lives with another adult with autism in his 20s.

They are among the pioneer beneficiaries of a pilot residential living facility programme by the Autism Resource Centre (ARC), which was set up in 2022 with support from Autism Association (Singapore).

The pilot is one of the few initiatives here to develop additional living options for people with disabilities (PWDs) besides living with family and institutionalisation. The need for alternative residential models is growing as Singapore ages and more caregivers die.

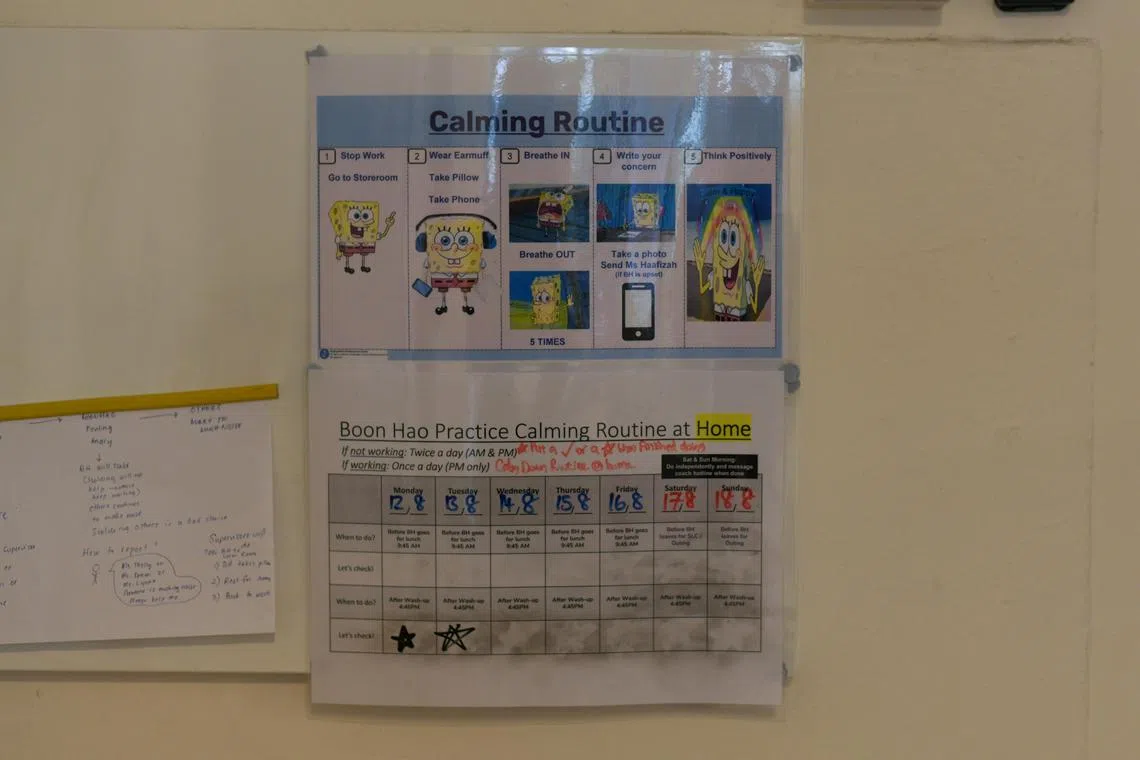

The flat is a sanctuary for Mr Neo to return to every day, meeting his basic needs of stability, safety and dignity, said Dr Sim Zi Lin, ARC’s psychologist and programme director.

Mr Neo had been at risk of not having a roof over his head after the death of his foster mother, who had been his main caregiver.

Dr Sim said some of the beneficiaries of the residential facility had faced similar circumstances or homelessness.

“We urgently set up the programme to address the needs of several individuals on the spectrum with extenuating circumstances,” she said.

The programme currently has five residents, who live in several units in the same block of flats. An on-site residential coach offers training and support.

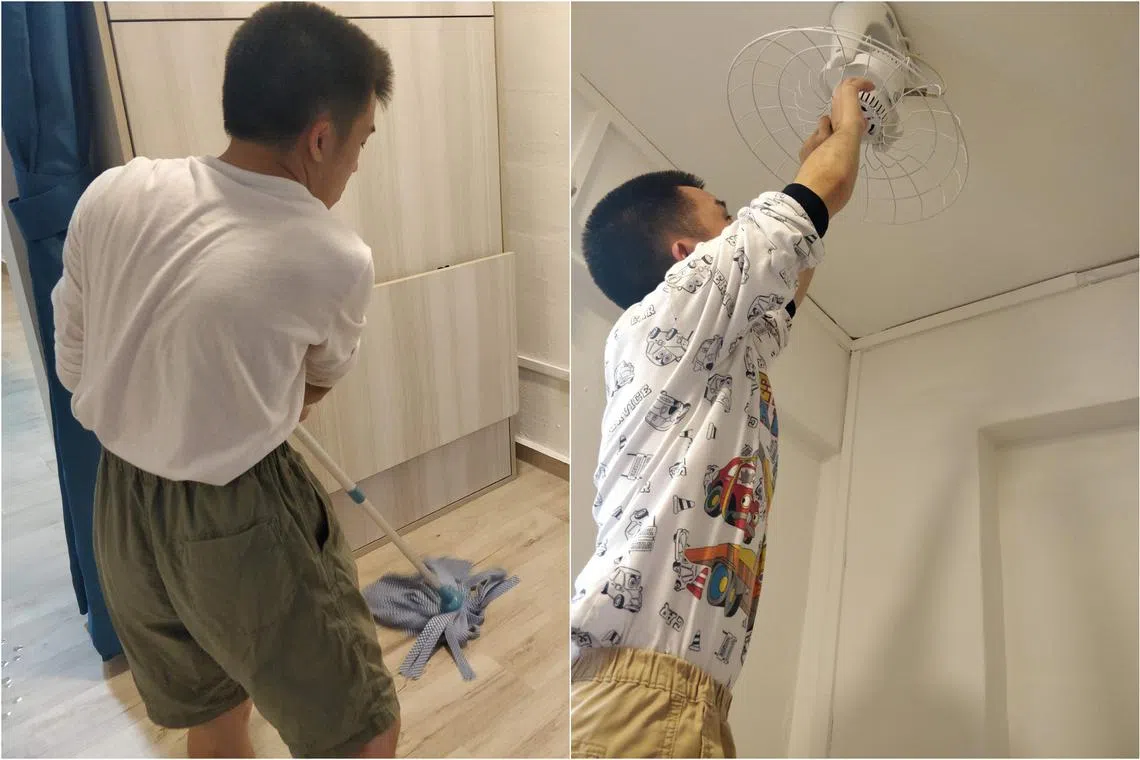

Mr Neo Boon Hao has learnt how to sweep and mop the floor, and also fix a fan himself.

PHOTOS: AUTISM RESOURCE CENTRE (SINGAPORE)

“I like learning together with them and living independently,” said Mr Neo, who lived with his foster mother in Tampines before she died. “I’ve learnt how to sweep and mop the floor, clean the toilet, do the laundry and the bedsheets too.”

He added that it is convenient for him to walk from home to his workplace, the Professor Brawn Cafe at Pathlight School. He enjoys visiting the Housing Board blocks in the estate – he particularly likes exploring the lifts – and doing grocery shopping with his coaches and other ARC residents.

Unlike in a gated and sheltered disability home, these residents have their own set of keys and are free to come and go, though they have to let their coaches know their whereabouts.

Some of them may visit their family members or dine with them on a regular basis. Mr Neo visits his foster sister on weekends and celebrates festive occasions with her.

The pilot programme

The programme fees for the facility are highly subsidised through ARC donations. The clients pay a service fee, which may be further subsidised based on their financial means and family support.

The residents get holistic support, such as social and community living training and guidance, employment services, and partnerships with public institutions to receive mental wellness or psychotherapy services.

The autism-friendly flat is designed to minimise sensory triggers.

ST PHOTO: RYAN CHIONG

“We guide them in decision-making by helping them understand the context and potential outcomes, but we ultimately respect their choices as adults,” Dr Sim said. “We wouldn’t be able to protect them from all the bad things in the world, but we are here to support them whenever they need help,” she said.

“Some of them are keen to have their own BTO (Build-To-Order) flats or HDB rentals one day, and we support them in working towards that goal,” said Dr Sim.

“Others may wish to return to their family home once their circumstances stabilise, and we work with them and their families on that front too.”

About 7,000 people with autism aged 18 and above are known to the Ministry of Social and Family Development (MSF) and disability agency SG Enable as they have applied for or enrolled in disability support schemes or programmes.

“More residential living options will better cater to the wide continuum of needs among those on the spectrum,” Dr Sim added. “This will also help alleviate the worries of ageing parents and caregivers.”

The residents get holistic support such as social and community living training and guidance.

ST PHOTO: RYAN CHIONG

Empowering PWDs through community living

Mr Fong Chong Meng found a home in Touch Ubi Hostel (TUH), a service of Touch Community Services, in June 2004, at the age of 31.

He was spotted loitering in his neighbourhood by someone in the community, who referred him to TUH. He was then unemployed, and his mild intellectual disability made him an easy target of bullying. He was living in a three-room HDB flat in Upper Cross Street with his father, who subsequently died.

TUH trains him in life skills, and helped him secure and maintain employment as a factory worker to pack towels for delivery. This November, the 51-year-old will be celebrating his 10th year with the company in Aljunied.

“I like my home here because I can make friends,” he said, adding that he can cook and perform household chores.

Every weekend, he returns to live by himself in his family flat. While he has been with TUH for some time, the aim is for him to be able to live independently in his family home.

Mr Fong Chong Meng found a home in Touch Ubi Hostel in June 2004 at the age of 31.

ST PHOTO: DESMOND FOO

Ms Ang Chiew Geok, group head of the Touch Special Needs Group at Touch Community Services, said TUH’s goal is to help trainees improve their life and job readiness skills, maximise their potential and integrate into the community, reducing their reliance on caregivers.

TUH houses 30 trainees, aged 21 to 62, in five HDB four- and three-room flats in Ubi, just a floor above the activity hall at the void deck. While all of them have mild to moderate intellectual disability, 30 per cent of them have other co-morbidities such as cerebral palsy, mild autism or deafness.

Since its inception in 1998, 40 trainees have graduated from the programme, with most of them back with their families. Six, however, have no housing alternatives and call TUH home.

In addition to three care staff who attend to their day-to-day care needs, there are three life skills coaches who conduct individual and group training in areas like financial resources, employment, psychological well-being, personal, social, daily living and community living skills.

“Being situated in the community has allowed our trainees to have the opportunity to experience communal living in a natural environment,” Ms Ang said.

“This serves as an excellent training ground for them to improve their independent living skills as they learn to apply life skills taught in a real-life setting.”

Mr Amos Kang, 45, TUH’s life skills coach, said: “We get to know them and find out about their learning disabilities, then we tailor specific training for each individual.”

For Mr Fong, who has never received formal education, this includes money management.

Eventually, TUH will help facilitate his transition back home in preparation of his “graduation”, by conducting customised home-based support to help him ease into living more independently at home.

Building an inclusive community

Community support is integral to the success of adult PWD housing schemes.

ARC staff visited the immediate neighbours of its residential facility to explain its residential programme and provide them with a contact number should they have concerns or questions.

“Like everyone living in the community, our clients also frequently tap services in the neighbourhood, such as meals at the nearby coffee shops, clinics, (getting) haircuts, either independently or with the support of residential coaches,” Dr Sim said.

“Such participation in the community has allowed natural support to develop – people in the neighbourhood have been generally friendly, understanding and helpful.”

There have been no complaints from the neighbours so far, she added. Neighbours also check in on the residents if they hear them shouting during occasional escalations, or inform the coaches.

Madam Siti Nur Aisha, 35, lives in a rented unit on the same floor, and said her neighbours are “normal residents” who say “hi” and “bye” to her when they meet.

The housewife added: “They are also human beings. They should be living in the community like us.”

Dr Mark Chui Wai Mun, a general physician with Doctor Anywhere in Ang Mo Kio which Mr Neo visits, said the clinic has spoken to the ARC team and is eager to help improve support for its residents, such as by allocating additional time for their appointments to provide more comprehensive and attentive care.

TUH also actively engages its community partners, including the coffee shop stallholders, general practitioners, dentist, supermarket and store holders, to create greater awareness on how to communicate with its trainees, and build an ecosystem of support.

For example, instead of providing meals at TUH, it intentionally creates learning opportunities for the trainees to step out confidently to buy lunch at the coffee shop and run errands in the neighbourhood. In turn, the trainees design festive cards to thank the community partners to build goodwill.

Touch’s Ms Ang said it is expected that some members of the public may not be receptive to its trainees in the community, and this is often due to a lack of knowledge about people with special needs.

“They may not fully understand their behaviours or know how to support them,” she said.

“However, by building awareness and sharing simple handles on how they can support persons with special needs, we have seen improved receptiveness towards our trainees.”

With increased positive exposure or interaction they have with the trainees, some people have also changed their attitudes, making the effort to care and support them, building inclusiveness in the community, she said.

“We are truly encouraged to see the community embracing PWDs and taking the effort to learn to communicate with our trainees as they have become a familiar sight in the neighbourhood,” she said.

Among those in the community is eyebrow therapist Reanne Ubonratyakab, a former hairstylist who walked into TUH three years ago to volunteer her hairstyling services to the trainees.

The 47-year-old, who lives in an adjacent block, said: “At first, I was worried if I could communicate with them, but they are actually very well mannered and friendly.”

Madam Su Hai Wei, who owns Delicious Ban Mian at the coffee shop in the same block, said the TUH trainees call her “sister” or “auntie” whenever they see her in the neighbourhood or at the bus stop.

“You can’t tell they are disabled. Sometimes they do not bring enough money for their food, but it’s okay,” the 52-year-old said, adding that she gives them small discounts occasionally.

Expanding the programmes

Dr Sim said all residents in the ARC facility have shown a marked increase in their quality of life after moving into the residential programme. These range from having greater social engagement to even simple things like better sleep.

They also have an increased breadth and depth of skills for greater independence in residential living, such as household and money management, leisure skills and community participation.

ARC hopes to grow its programme to accommodate up to eight residents, and develop other residential living options.

It also plans to scale up its independent living skills training to support more individuals in community living.

However, one hurdle lies in securing longer-term leases for the homes beyond the yearly renewal, which would support long-term planning for the residents, said Dr Sim.

Other challenges include ensuring a pipeline of suitable and competent residential coaches and funding, and matching suitable residents to live together.

TUH’s expansion plans are currently limited as all the surrounding units are owner-occupied. While using rental flats is a possibility, securing approval for several units to be used as a single facility will require negotiations with the authorities, said Ms Ang.

PWDs without alternative caregiving arrangements may be enrolled into adult disability homes.

There are currently 11 MSF-funded adult disability homes that provide long-term residential care to PWDs who are destitute or neglected or whose caregivers are incapable of or unavailable to care for them.

But the Enabling Masterplan 2030

“To support that plan, it is necessary to equip PWDs with the necessary independent living skills now so that when the housing options are available, our people are ready for it.”

She emphasised that it is possible for PWDs to live in the community, provided they are trained in the necessary life skills and can adequately sustain these skills. It is also necessary to empower the community they live in to work with the professionals to give PWDs the necessary support.

“This is the way forward,” she said. “Ageing in place should apply to PWDs as well.”

An Enabling Masterplan 2030 task force looking into developing new community living models to enable people with disabilities

PWDs who lack caregiving support or whose caregivers are getting on in age can seek help from SG Enable and the Special Needs Trust Company to plan ahead for future care arrangements.

Dr Eunice Tan, head of special education at the Singapore University of Social Sciences’ S R Nathan School of Human Development, said living in the community should not be limited to people with low support needs.

It should be adapted for all adults with varying levels of disabilities, just like in Canada, the United States and Australia.

“This is a human right – to be included and to participate in the community regardless of abilities,” she said. “Regardless of our abilities, we all want to be accepted, respected and loved. No one wants to feel that they are being belittled, or to be ‘hidden’ because they are different from others.”