ST Explains

What is the significance of Singapore’s carbon trading pacts on firms and the economy?

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Experts say that carbon trading could also help firms save money and boost investments into climate-friendly projects in developing countries.

ST PHOTO: LIM YAOHUI

- Experts say that carbon trading could also help firms save money and boost investments into climate-friendly projects in developing countries. Carbon credits could also become an investible asset class, similar to other commodities.

- Carbon credit prices vary widely, so firms should diversify their credit portfolio across project types and countries.

- Buyers face risks like fraudulent credits; experts advise robust quality screening, reputable sellers, and clear contracts to minimise these potential issues.

AI generated

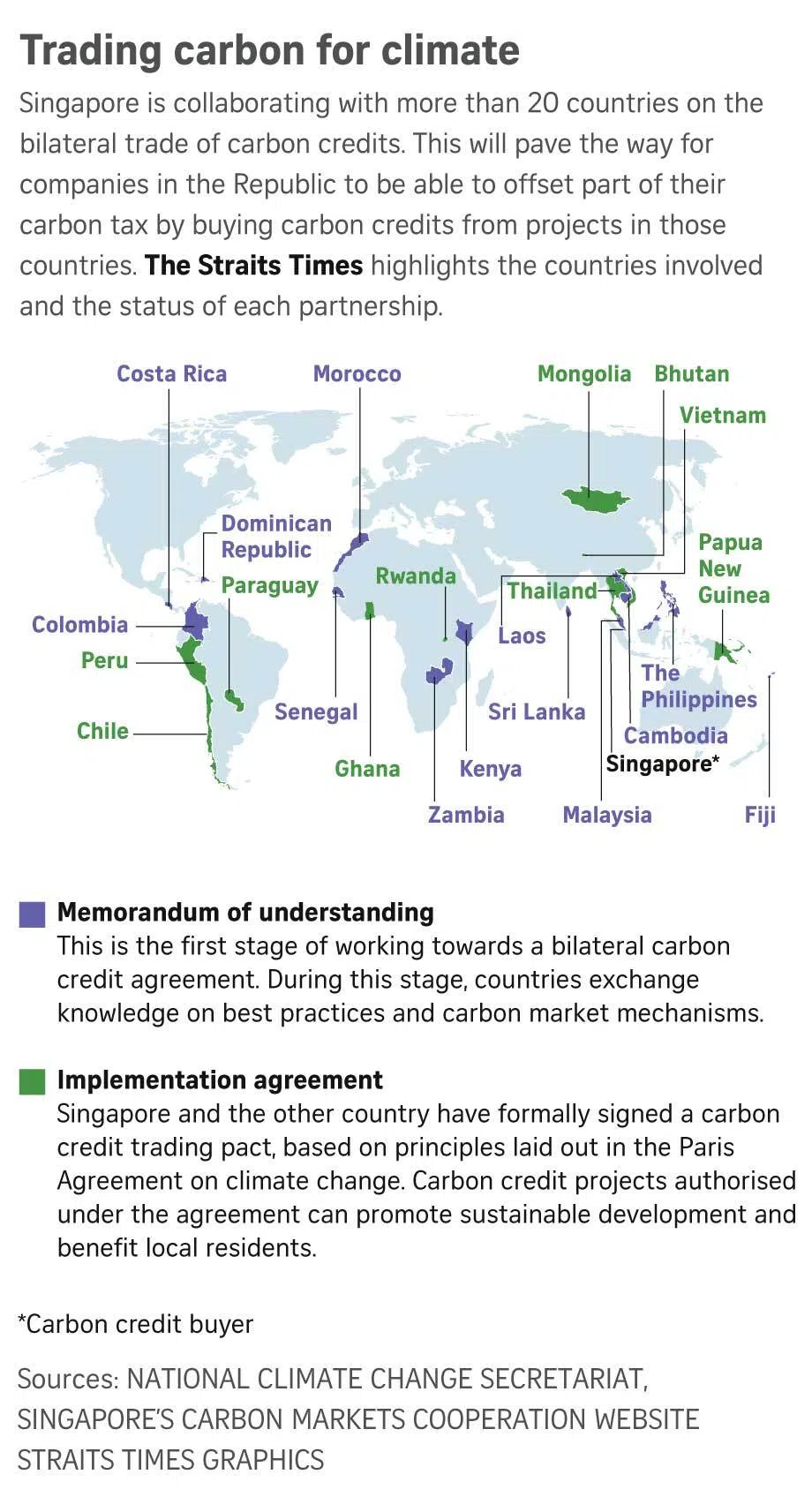

SINGAPORE - Singapore’s efforts to source for carbon credits from all over the world are paying off, with 10 such deals inked since end-2023

As at early October, the Republic has signed implementation agreements with Ghana, Papua New Guinea, Chile, Bhutan, Peru, Rwanda, Paraguay, Thailand, Vietnam and Mongolia.

These agreements pave the way for carbon tax-paying companies in Singapore, as well as the Government, to buy credits from carbon projects in these countries to offset some of the companies’ planet-warming emissions.

But these credits are shaping up to be more than just a way for the Republic or companies here to meet their climate commitments.

Experts say that carbon trading could also help companies save money and boost investments in climate-friendly projects in developing countries. Carbon credits could also become an investible asset class, similar to other commodities.

The Straits Times speaks to carbon market industry watchers to pin down the economic implications of the international carbon market for Singapore and South-east Asia.

What are carbon credits?

One carbon credit represents one tonne of carbon dioxide (CO2) that is either prevented from being released – by saving a forest from the axe, for example – or removed from the atmosphere, such as from a direct air capture plant.

For companies, buying carbon credits is one way to reduce their carbon footprint, in order to meet their voluntary targets, or to fulfil regulatory requirements.

For example, carbon tax-paying companies in Singapore are allowed to buy carbon credits to offset up to 5 per cent of their tax bill. These credits would come from carbon projects that Singapore has carbon trading deals with.

At the national level, Singapore had earlier estimated that it would use eligible carbon credits to offset about 2.51 million tonnes of emissions a year over this decade to meet its national targets under the Paris Agreement.

How can carbon credits help companies save money?

If the price of the credits is lower than the cost of paying the carbon tax, buyers could reap some economic savings.

The Republic’s carbon tax is set to rise from the current rate of $25 per tonne of greenhouse gases emitted to $45 per tonne in 2026. By 2030, the tax rate could be $50 to $80 per tonne.

“As carbon tax rates rise, more and more companies will be interested in buying carbon credits as long as the credit price is lower than the carbon tax and the company’s (decarbonisation) cost,” said Dr Kim Jeong Won, a senior research fellow from the NUS Energy Studies Institute (ESI).

At the same time, the carbon revenue flowing from emitters to carbon project developers helps in the establishment of climate-friendly initiatives in the host country, which is usually a developing country.

“Companies want credits that not only meet carbon compliance but also deliver community, biodiversity and adaptation benefits,” said Mr Sandeep Roy Choudhury, co-founder of home-grown carbon project developer VNV.

There are two main types of carbon credits – nature-based ones like reforestation, and technological ones that include switching from pollutive firewood to cleaner cooking stoves.

What is the price range of carbon credits?

The price of credits can range widely depending on the types of projects. Other factors can also shape prices, including buyers’ demand for high-quality carbon credits.

Credits are deemed to be of high quality if they help reduce or remove emissions from the atmosphere in a way that can be trusted and verified. Projects must also be additional, which means that the emission reductions would not have happened without the revenue from carbon credits.

Mr Choudhury said projects that remove CO2 from the atmosphere – such as direct air capture or reforestation efforts – tend to produce more expensive credits.

This is because of high upfront costs and the need for long-term monitoring. For reforestation, the capital is provided early, but the credits are generated much later because trees need years to grow and sequester carbon. These projects last decades and require years of monitoring.

One credit produced through direct air capture can cost US$500 (S$649), according to carbon intelligence platform Sylvera.

Projects that involve replacing pollutive sources and preventing greenhouse gases from being released – including building new renewable energy plants, forest protection and energy efficiency projects – produce carbon credits at mid-tier prices, Mr Choudhury added.

Credits arising from renewable energy projects cost an average of $2.67, according to Ecosystem Marketplace, a global environmental finance news and analysis site. As renewable energy projects can now be cheaper than fossil fuels, several renewable energy offsets are no longer considered “additional” since they would have been developed even without the carbon revenue.

Credits from forest conservation initiatives are dubbed Redd+, or reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation. The average price of one Redd+ credit was around $6 in 2024.

But S&P Global Commodity Insights, which analyses the energy and commodities markets, said credit prices for tradeable Redd+ projects in the region have seen a sharp uptick in the past few months. This is partly due to higher-rated projects that carry additional benefits such as biodiversity conservation and job creation.

“Buyers have shown willingness to pay up to US$10 (per credit), on the back of a rise in demand for projects like Indonesia’s Katingan and Cambodia’s Keo Seima, while supply is also limited in the market,” said S&P.

How do companies decide what types of credits to buy?

Demand for cheaper credits could initially be fuelled by carbon tax-paying companies looking to offset their emissions at the lowest possible cost.

In the long term, however, companies are likely to gradually diversify the types of carbon projects they source from in case low-cost credits are not of the best quality, added Dr Kim.

This is because some projects could fail to reduce planet-warming emissions as claimed, and buying such credits could expose the companies to reputational risk.

Associate Professor Daniel Lee, director of the NTU Carbon Markets Academy of Singapore, said the price of credits will not be the sole determinant for buyers, as companies will also consider a carbon project’s track record for producing the agreed amount of quality credits on time.

Failing to secure the required number of credits within a certain timeframe could mean companies incur a higher cost by sourcing for more expensive credits elsewhere, or end up paying the full carbon tax.

Experts urge buyers to source their credits from a mix of project types and countries, to avoid putting all their eggs into one basket.

Singapore’s carbon trading agreements reflect a range of project types at different price points, which gives buyers the flexibility to build diversified portfolios, said Mr Choudhury.

At least four of the 10 countries have a list of pre-approved project methods, which gives buyers a glimpse of the types of credits they could invest in.

For example, projects in Rwanda could be focused on renewable energy, energy efficiency and clean transport projects. Bhutan could offer nature-based projects.

Companies should assemble a portfolio of credits that balances carbon reductions and removals, and nature-based and technology-based solutions from a mix of geographies, said Mr Anshari Rahman, policy and analytics director from climate investment firm GenZero.

Some carbon projects have been plagued by scandals. Will that be risky for buyers?

Issues with carbon projects have made headlines in recent years, over fraudulent credits or claims that the project had affected the rights of indigenous communities.

In 2023, for instance, The Guardian news outlet reported that more than 90 per cent of rainforest credits did not represent genuine carbon reductions.

In late 2024, a US carbon offsets developer C-Quest Capital was accused of faking emissions-reduction data as part of a scheme to obtain millions of carbon credits and secure more than US$100 million in investment.

NTU’s Prof Lee said a buyer’s risk can be minimised, but not eliminated. Companies should select reputable sellers to buy from, and ensure that contracts clearly spell out who will be responsible for specific risks. Buyers should also ensure that the risks they take on match what they are comfortable with, he added.

Dr Kim from ESI said companies should have robust quality screening for the credits they buy, by using internal standards and third-party verification.

“Firms could use hedging mechanisms by engaging law firms and insurance companies in the contract process,” she added.

Mr Choudhury added: “My advice to buyers is to treat credits like an investment portfolio: Spread purchases across (methods), project types and regions, so that if one category is questioned later, the whole portfolio isn’t exposed.”

Carbon credits “behave more like financial instruments than simple compliance payments” like the carbon tax, so risk management has to be multi-layered, he said.

Can carbon credits be considered an investible asset?

Yes. As the carbon tax is set to rise, tax-paying companies could secure credits in advance and retire them later when the gap between the credit price and tax rate is wider, said Mr Choudhury.

Mr Anshari said this could be a strategic move. Carbon credits are retired or “expired” once publicly declared to be used to meet their climate obligations, making them no longer tradable in the market.

Ms Marianne Tan, associate director of policy and strategy for the Asia-Pacific at climate consultancy South Pole, noted that carbon tax-paying companies here will eventually be competing with a much larger global market for a limited supply of credits

Buyers should consider long-term partnerships with reputable project developers and explore innovative ways to source credits or make direct investments.

“That way, you’re helping to grow the supply of credits your business will need down the line, while also securing access to them in advance,” added Ms Tan. South Pole is also a carbon project developer.

In theory, it is also possible for companies to buy credits earlier and resell them to other companies at a higher price down the road when demand spikes, said Mr Choudhury.

But most serious buyers still prioritise securing a credible supply of offsets for their own decarbonisation, he added.

Mr Shawn Woo, Asia-Pacific’s head (commercial) at climate solutions provider 3Degrees, foresees that some companies in Singapore will not just buy credits, but will run a managed portfolio under which they also trade the credits, as has been seen in other markets historically.