What impact will UN climate conference COP30 have on South-east Asia?

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

The COP30 climate conference ended nearly 27 hours late.

ST PHOTO: ANG QING

- COP30 concluded with an agreement on adaptation indicators to track resilience to climate change, though some countries voiced concerns about financial obligations and clarity.

- Developed nations agreed to strive to triple adaptation finance for developing countries by 2035.

- COP30 saw no agreement on phasing out fossil fuels, but a "just transition" mechanism was established to support communities in shifting to a low-carbon economy.

AI generated

SINGAPORE - On Nov 22, negotiators left UN climate conference COP30 in Brazil with another watered-down deal, amid a year of record heatwaves, deadly storms and geopolitical tensions.

Following two weeks of talks in the Amazonian city of Belem, COP30 ended nearly 27 hours late. The discussions were fraught with disagreements over fossil fuels and finance, but 194 countries at the annual summit finally came to an agreement on the path forward for climate action.

The outcome from the annual UN climate summits is significant as it marks a political commitment from most of the world to pursue actions to tackle climate change. What appears in the text – and what does not – sends a message on what countries are willing to do to limit global warming.

The Straits Times looks at the bittersweet implications of COP30 for developing South-east Asia.

Adapting to climate change

Verdict

Adaptation refers to actions that help reduce people’s vulnerability to climate impacts, such as building sea walls to keep out rising tides.

At COP30, one of the key expected outcomes of the event was for countries to agree on a set of indicators

The set of indicators will help countries track progress to meet a key element of the Paris Agreement – the global goal on adaptation. This is a collective commitment to help the world strengthen resilience to climate change impacts.

An initial list of 100 indicators drafted by experts over two years was whittled down to 59. They cover areas such as water, agriculture and health.

Countries do not have to report on all of these indicators, but can choose those most relevant to them. This is because climate change impacts different parts of the world differently.

However, parties voiced concerns during COP30 about whether the indicators would add financial obligations on them.

They also said they did not have enough time to review the latest list of indicators, which had been decided at 3am on the penultimate day of the conference. Some of the indicators had also been modified from the list prepared by experts, and some countries thought them unclear.

For example, experts had noted that global preparedness against climate shocks could be gauged based on the number of parties that have established multi-hazard early warning systems. However, the final indicator set outlines a vague metric of the “level of establishment” for these systems.

That an agreement on the indicator list could be reached despite the tricky negotiations is considered a win for the region, experts say.

Residents evacuating to a safer place on Nov 11 after flooding during Super Typhoon Fung-wong.

PHOTO: AFP

South-east Asia is among the regions most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. Millions living in long coastlines and densely populated low-lying areas are at risk of weather extremes and rising sea levels driven by global warming.

Activists from the region brought some of this vulnerability into the COP30 venue.

Filipino activists were seen at protests there, reminding delegates of the human toll of intensifying natural disasters. They highlighted back-to-back typhoons that slammed into the archipelago in November, which barely gave communities time to recover.

They also called on the world to pump more funds to help reduce the vulnerability of countries to climate impacts.

Dr Theresa Wong, who was among the 78 experts who drafted the initial list of indicators, said countries in South-east Asia can use the indicators to track effective strategies and actions that support livelihoods, save lives and shore up economic and food security.

For example, if countries track the resilience of their health facilities to climate-related hazards, they can take steps to improve their ability to protect lives.

She added that the outcome is a welcome development, as COP30 laid a foundation for the adaptation community to build on, despite the challenging geopolitical environment.

Dr Wong, who is head of science for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Working Group II Technical Support Unit, added: “I hope this next period of work will improve the rigour and balance of the (indicators) to the point that they have wide acceptance not only politically, but for those who must do the tracking.”

The IPCC is the UN’s climate science body. Working Group II focuses on the vulnerability of socio-economic and natural systems to climate change, and ways to deal with the impacts.

Mr Andre Ferretti, manager of biodiversity economics at Brazil’s non-profit Boticario Group Foundation for Nature Protection in Curitiba, told scientific journal Nature: “The adoption of a package of adaptation indicators, although imperfect, is a win.

“Reporting and monitoring what is being done in adaptation is fundamental to understanding which regions need more attention, which populations are being most affected, and also to requesting resources.”

However, some parties, including the European Union and West African nation Sierra Leone, were opposed to the blanket adoption of the indicators in their current form.

“The global goal on adaptation is not just a framework. It is a vision born in Paris 10 years ago, a vision of a safer, more resilient future for the most vulnerable,” said Sierra Leone’s Minister of Environment and Climate Change Jiwoh Abdulai.

He called the indicators a means of illuminating which adaptation measures are working, and where support is urgently needed. However, Sierra Leone was among the countries that called for continued work on the indicators, as the current list was “unclear, unmeasurable, and in many cases, unusable”.

It remains to be seen if countries will start using the indicators agreed at COP30, as they will be refined through a two-year process.

The Adaptation Finance Now protest outside the COP30 Blue Zone at about 8.20am. Protesters were told by the military to disperse after roughly half an hour.

PHOTO: JASON VALENZUELA OF ASIAN PEOPLES’ MOVEMENT ON DEBT AND DEVELOPMENT

Another promising development at COP30 for South-east Asia was the agreement by countries to make efforts to at least triple finance for developing countries to adapt to climate change by 2035.

This amounts to raising existing funds to roughly US$120 billion (S$155 billion) annually. This sum will be part of an earlier-agreed-on climate finance target of raising US$1.3 trillion for climate initiatives

Neglected and under-resourced for years, adaptation has seen slow progress, as much of the world’s attention has been focused on mitigation, or efforts to reduce planet-warming greenhouse gas emissions.

For developing countries, adaptation efforts are further hindered by a lack of funds to cope with increasing onslaught from extreme weather events.

Finance from developed countries is critical for poorer countries to implement adaptation strategies. Discussions on this front were some of the most contentious at COP30.

Developing countries and blocs, such as Indonesia and the Alliance of Small Island States, which includes Singapore, had initially wanted adaptation finance to be tripled by 2030.

The deadline to achieve this was pushed back by five years, but observers welcomed the political commitment from developed countries to contribute more to adaptation finance.

“While 2035 is a longer timeframe than developing countries asked for, the text includes a call for developed countries to scale up (adaptation finance) steadily over time, providing reassurance following aid cuts,” said independent climate change think-tank E3G.

The commitment is a step forward to provide much-needed support for adaptation programmes and projects in the Philippines, said Mr John Leo Algo, national coordinator of Philippine climate action network Aksyon Klima Pilipinas.

“With COP30 over, our eyes are now back into what the Philippine government does next,” he added. “There is no climate justice without good governance.”

Officials, lawmakers and construction firm owners in the Philippines have come under fire for corruption and mismanagement of government-funded flood control projects there, where towns have recently been flooded by typhoons.

For clean energy non-governmental group 350.org, however, the outcome was rhetoric.

Not only was the timeline delayed, the outcome also did not state a baseline from which adaptation finance should triple. It also did not provide any guarantee of finance that did not induce debt.

Climate finance can take on many forms, including grants and private loans. Loan-based instead of grant-based climate finance can wind up entrenching vulnerable developing countries deeper in debt.

“Front-line communities, including indigenous and traditional peoples, are also and once again left waiting for direct access to finance while the EU, Japan and Canada stalled progress,” said 350.org.

Cutting greenhouse gas emissions

Verdict

Another keenly watched outcome of COP30 was whether countries would agree to phase out the root cause of modern climate change – fossil fuels.

As the conference entered its politically charged second week, momentum against fossil fuel

More than 80 countries signalled their support for a road map to wean off fossil fuels. But they failed to come to an agreement with a bloc of states with fossil-fuel dependent economies, which includes India, Russia, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

Also in attendance at the negotiations were more than 1,600 fossil fuel lobbyists, according to reports.

Nations were expected to submit their new climate pledges for the year 2035 by COP30, but many missed the deadline.

Based on new climate goals submitted, the world will heat up by between 2.3 deg C and 2.5 deg C above pre-industrial levels by 2100, according to the UN’s latest report.

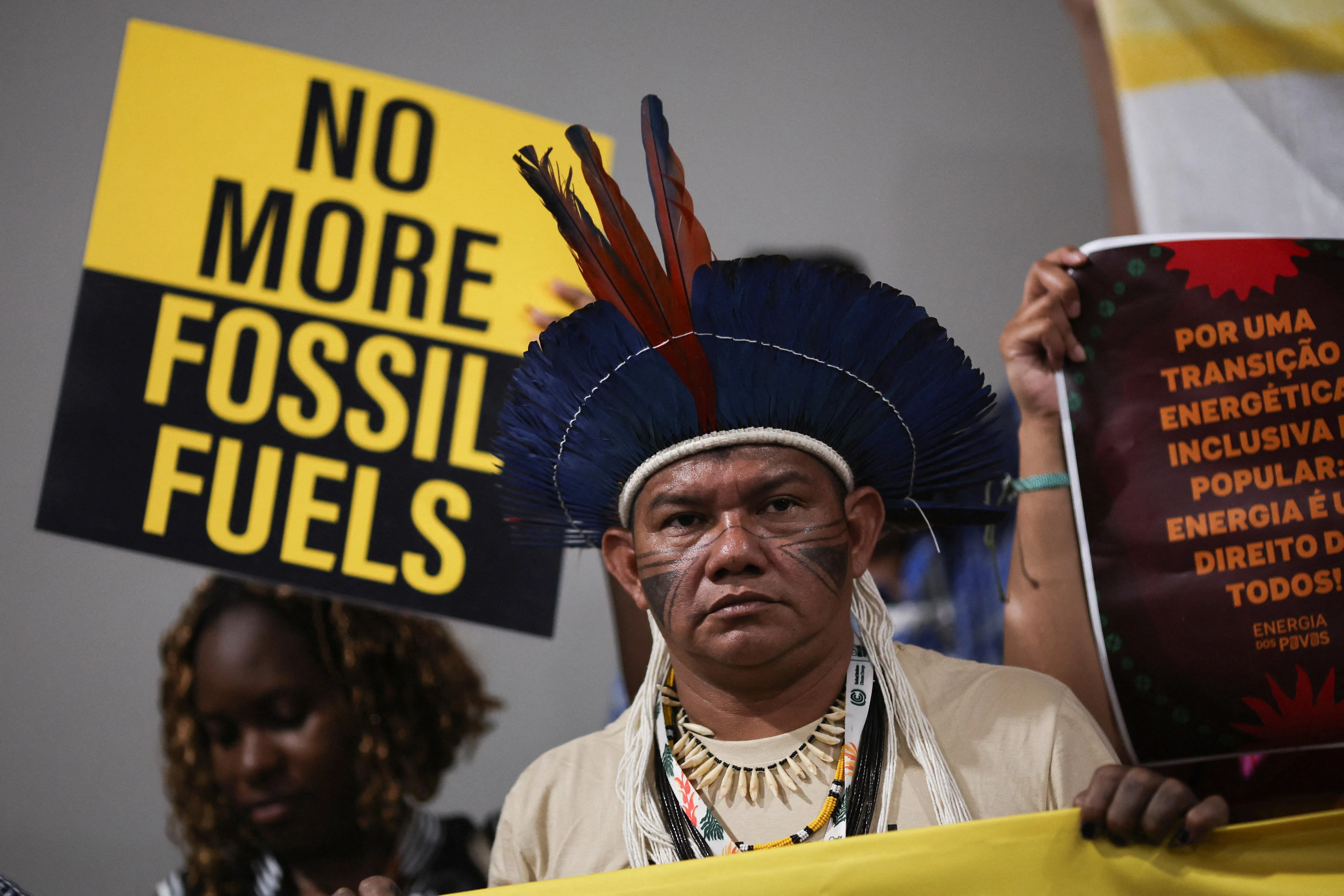

Activists and indigenous people taking part in a protest against fossil fuels during COP30.

PHOTO: REUTERS

This exceeds the target set out in the Paris Agreement, under which countries agreed to pursue actions to cap warming to well below 2 deg C, and ideally, 1.5 deg C, above pre-industrial levels.

Exceeding warming by this threshold can result in more catastrophic climate change impacts, such as expanding the geographic regions where diseases like malaria can spread, incurring higher costs for adaptation and causing damage to crops.

In October 2025, it was confirmed that the world’s warm-water coral reefs have experienced unprecedented levels of heat stress, which turned many of these colourful underwater gardens a deathly white.

The Fossil Fuels Funeral procession in Belem on Nov 15, where indigenous leaders demanded an end to fossil fuels.

PHOTO: ARTYC STUDIO

At COP30, a road map to phase out fossil fuels vanished from the final text.

Instead, the COP30 Brazilian presidency announced that such a plan will be developed outside the official proceedings.

The first International Conference on the Just Transition Away from Fossil Fuels is to be held in Santa Marta, Colombia, in April 2026.

This was announced by the Latin American nation at COP30, when 24 countries publicly signed the Belem Declaration for a just transition away from fossil fuels. Cambodia was the only South-east Asian representative to join the coalition.

For Mr Tara Buakamsri, co-founder of campaigning group Greenpeace South-east Asia & Climate Connectors, the presidency’s support of the conference in Santa Marta keeps a “crucial door” in the conversation open.

“For ASEAN – where fossil fuels still dominate almost four-fifths of the energy mix – the question is whether we show up as architects of that road map or as bystanders to it,” said the former country director of Greenpeace Thailand.

“The Santa Marta process must now become the place where ASEAN and Thailand finally help turn those hooks from COP30 into a real, equity-grounded, fossil-free pathway – rather than letting the region be the last bastion of coal, fossil gas and imported liquefied natural gas.”

Coal, the dirtiest form of fossil fuel, accounted for 80 per cent of ASEAN’s power sector emissions in 2023. Natural gas releases less planet-warming emissions when burned, but is still a fossil fuel.

Coal is the largest source of carbon emissions globally, and in Asia, coal plants contribute to one-third of the region’s emissions.

PHOTO: AFP

It remains to be seen how ASEAN will respond to voluntary initiatives launched at COP30 to strengthen the cutting of greenhouse gases and improve adaptive efforts.

Associate Professor Linda Yanti Sulistiawati, a research fellow at Asia-Pacific Centre for Environmental Law, noted that South-east Asia has the youngest coal fleets globally, making early retirement of these coal plants costly but essential.

The region’s diverse energy mix makes it difficult to agree on uniform mitigation actions to phase out fossil fuels, so other areas of collaboration could be easier points of convergence, she added.

For instance, ASEAN can cooperate on sharing renewable energy

“Renewable energy and carbon markets are framed as opportunities for growth rather than restrictions. They attract investment and create jobs without requiring explicit commitments to phase out fossil fuels,” Prof Sulistiawati said. “Similarly, forest preservation is supported by global finance and enhances national pride, making it politically easier than coal retirement.”

Ensuring no one is left behind

Verdict

The concept of a “just transition” is gaining traction globally. It is underpinned by the belief that a low-carbon economy should not leave any communities behind, especially those whose livelihoods rely on fossil fuels or carbon-intensive sectors.

At COP30, countries agreed on a mechanism to ensure that just transition initiatives will be discussed, coordinated and supported at the climate forums.

This commitment appeared in the final COP30 outcome text, and was received with jubilant cheers and applause from developing countries and civil society groups alike as it was gavelled through.

Activists from the Make Polluters Pay coalition urging Big Oil companies to fund climate solutions on Nov 19 at COP30.

PHOTO: REUTERS

The proposal by the Group of 77 and China – a coalition of developing countries representing about 80 per cent of the world’s population – will pave the way for more just transition schemes to be implemented globally.

This will be done with the help of international cooperation, technical assistance, capacity-building and knowledge on the restructuring of the global energy economy in a fair and equitable manner.

Singapore chief negotiator for climate change Joseph Teo and Italy’s Federica Fricano co-chaired the negotiations on this front.

A representative from G77 and China, speaking at the closing plenary of COP30, couched the programme as a “symbol of hope and solidarity and the promise that the international community will stand together to ensure that no nation and no community is left behind”.

A commentary by non-profit sustainability think-tank World Resources Institute hailed the mechanism as the furthest a COP has gone to address workers’ and communities’ rights.

Civil society groups called for ambition to be backed by resources.

Indigenous people demonstrating at COP30 in Belem on Nov 21.

PHOTO: EPA

The rights of indigenous people, as well as their ownership of land and traditional knowledge, were recognised in Belem for the first time, for their role in fighting against climate change.

This recognition was a key win for executive director of Indigenous Peoples Rights International Joan Carling, who told environmental media outlet Mongabay that the next battle will be implementing the assurance on the ground.

The summit was also attended by the highest number of indigenous people, a key emphasis by the Brazilian presidency. About 3,000 indigenous people were expected to attend COP30-related events. They travelled from the nearby Amazon rainforest and as far as Indonesia and the Pacific Islands.

It is unclear how many entered the access-limited Blue Zone, where negotiations take place, with estimates ranging from 360 to 900, but their presence was certainly felt as participants’ affiliations were on full display through their colourful feathers, flowers and traditional garb.

For Prof Sulistiawati, who attended the conference, while representatives of indigenous people from Brazil were present in the COP30 venue, they were treated mostly as observers or guests, not as rights-holders or decision-makers.

Protecting nature

Verdict

For a conference dubbed the “Forest COP”, COP30 failed to secure a political commitment from the world’s leaders to safeguard the lungs of the planet, which absorb huge amounts of planet-warming carbon emissions.

The Brazilian hosts had insisted on hosting the summit in Belem at the edge of the Amazon rainforest to spotlight the threats faced by the tropical ecosystem, despite the lack of sufficient infrastructure there to host the more than 50,000 delegates who showed up.

But, like the push for a road map to transition away from fossil fuels, Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva’s proposal for a road map against deforestation failed to make it to the final text.

Securing political commitment for forest protection is critical for South-east Asia, given that the region is home to the world’s third-largest forested area, or 18 per cent of global forest cover.

The forest road map had been backed by at least 92 countries, according to Carbon Brief, including the Coalition for Rainforest Nations that Cambodia, Laos, Malaysia, Indonesia, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam are part of.

The road map would have required countries to show how they intend to meet the 2030 zero-deforestation pledge made two years ago at the Dubai climate summit.

But discussions on forests at COP30 were dominated by the other controversial issues of adaptation financing and fossil fuels.

People walking past an installation at COP30 by Brazilian artist Mundano, made for Greenpeace with ashes from Amazon forest fires.

PHOTO: AFP

In place of an international commitment, Brazil’s COP30 president said it would put forward a voluntary road map.

On the sidelines of the conference, more money and pledges were made to forests and oceans.

Brazil also launched its Tropical Forest Forever Facility, a fund that rewards tropical forest nations for keeping their forests with cash, at COP30. Brazilian Forest Service director-general Garo Batmanian told ST that the initiative will supplement a shortfall in donations for conservation in the Amazon rainforest.

“You’re always competing with famine, epidemics, rebuilding areas, disasters or war,” he said. “We thought about a different way of generating funds so it does not have this overreliance on donations.”

The facility, designed with Malaysia and Indonesia, is expected to also benefit those eligible in these partner countries, as well as people in Laos, Thailand and Myanmar, he noted.

The facility secured at least US$6.7 billion from five countries by the end of the conference. Of the contributors, both Brazil and Indonesia are also beneficiaries. But this falls short of the initial US$125 billion for the fund that Brazil had hoped to raise at COP30.

By the end of 2026, the initiative hopes to raise US$10 billion, said its architect Joao Paulo de Resende, who hopes Singapore can also pitch in for forests in its neighbouring countries.

He said: “Forests provide ecological services that benefit everyone, but the opportunity cost of keeping them intact is concentrated on the poor countries.”

However, the facility has been subject to criticism that it lacks accountability, among other things.