ST Explains: Cyclone Senyar was rare for S-E Asia – could a storm like it ever hit Singapore?

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Senyar was whipped up by a mass of circulating air from a monsoon surge in the northern part of the Strait of Malacca.

PHOTO: EPA

SINGAPORE – Since late November, floods and landslides have swept South-east Asia, claiming close to 900 lives

The region usually experiences a rainy season at the end of the year. But this time, other than the lashing rains, worry had swirled over a cyclone called Senyar that developed over the usually calm Malacca Strait.

This is a rare occurrence, as such rotating storms hardly happen along the Equator.

The Straits Times unravels the science behind the unusual cyclone that resulted from a confluence of weather events, and looks at how likely it is for Singapore to be hit.

What are tropical cyclones?

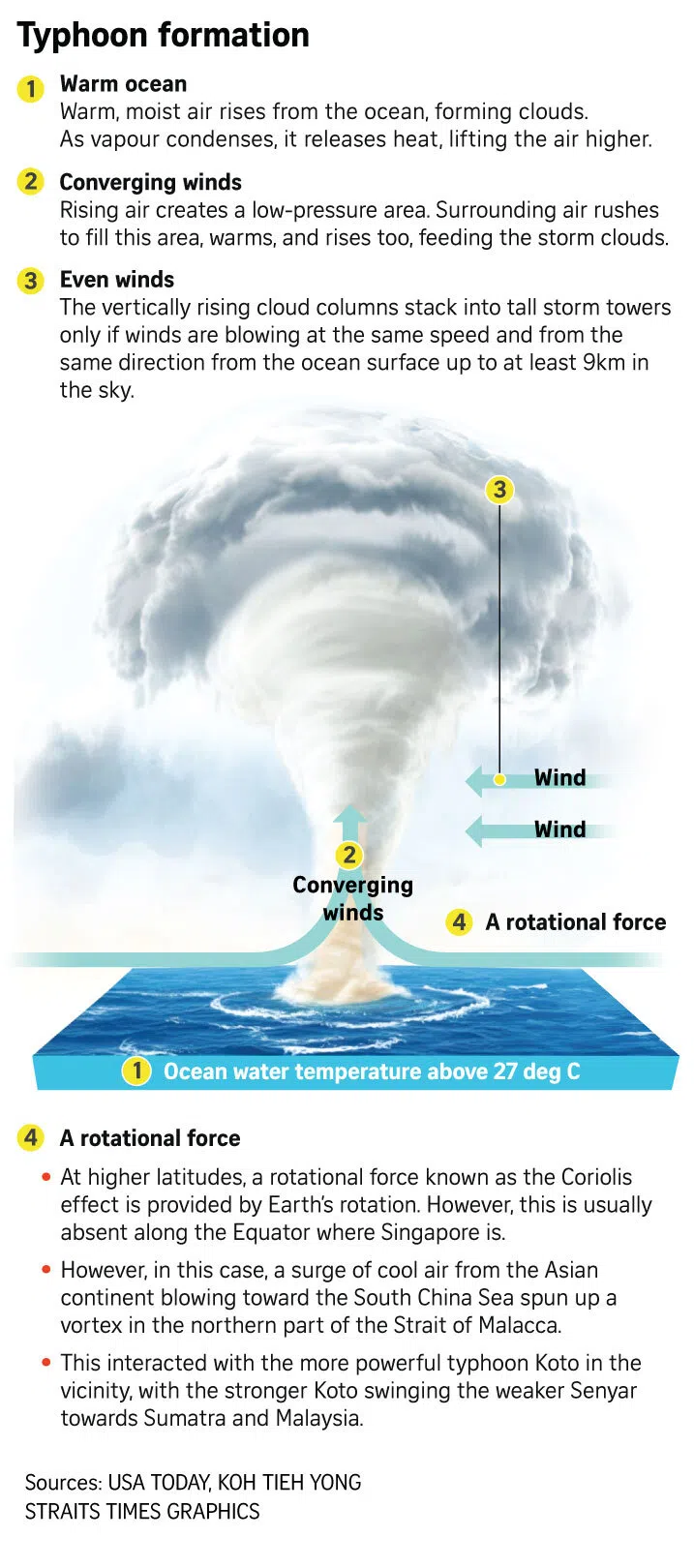

These are powerful storms that draw heat from warm water at the ocean’s surface to power horizontal, rotating winds, according to NASA.

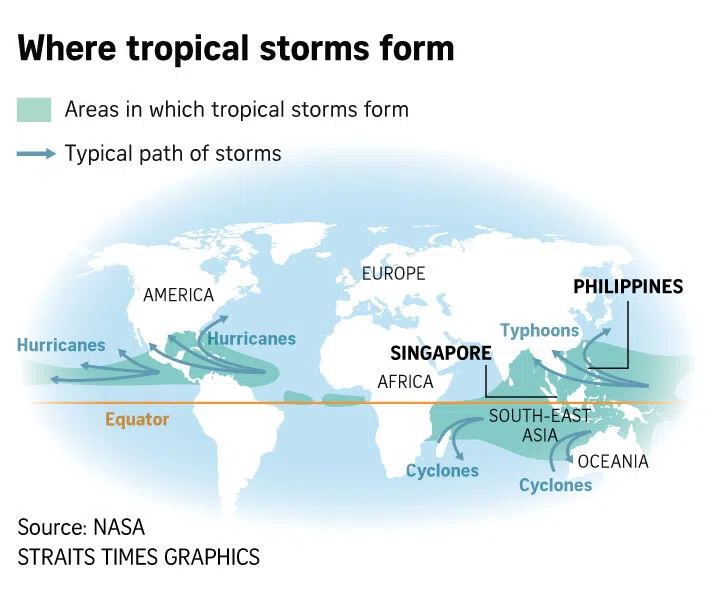

Typhoons, cyclones and hurricanes are the same phenomenon, but have different names depending on where they form.

They are called hurricanes when they develop over the north Atlantic Ocean, central-north Pacific, and eastern-north Pacific. They are known as cyclones when they form over the south Pacific and Indian Oceans.

Dr Koh Tieh Yong, a member of the Working Group on Asian-Australian Monsoon under the World Climate Research Programme, said only the strongest tropical cyclones formed in the north-west Pacific Ocean, including the South China Sea, are called typhoons.

“Senyar was not formed in the north-west Pacific and was not strong enough in any case to be called a typhoon,” said Dr Koh. Such storms are considered typhoons only when wind speeds reach about 119kmh.

Why is it rare for tropical cyclones to occur near the Equator, where Singapore is?

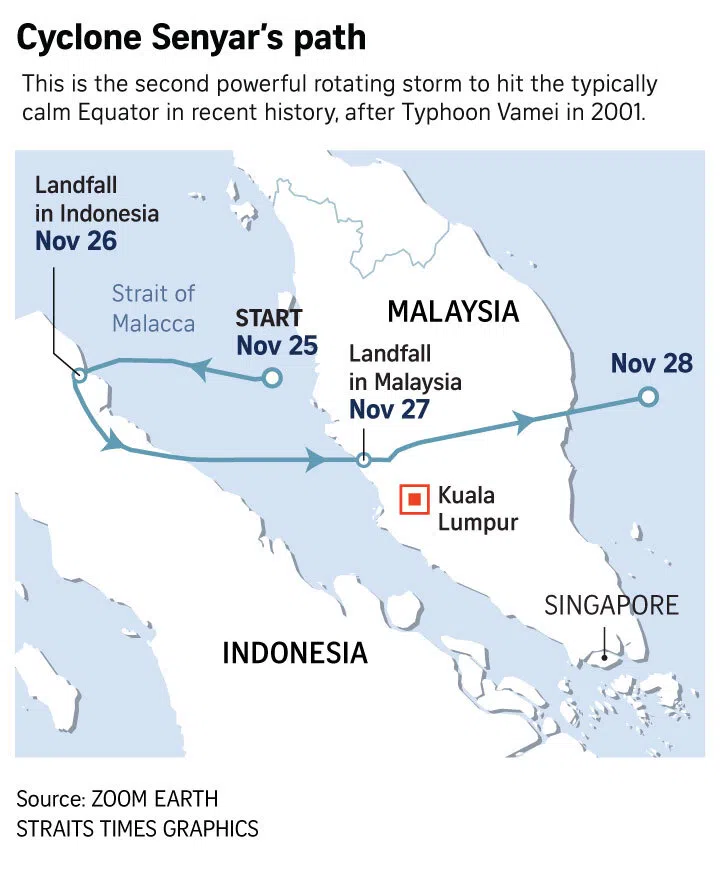

Since records began, only two such cyclones have happened.

Typhoon Vamei developed in 2001 about 150km north of Singapore.

Cyclone Senyar brewed in the Strait of Malacca

Tropical cyclones need a spinning force to form. For most storms, this spinning force comes from the earth’s rotation, known as the Coriolis force. This force is often too weak over the Equator, which is why such powerful storms are rarely generated here.

How did Cyclone Senyar develop?

It is rare, but not impossible, for a tropical cyclone to form near the Equator.

For Cyclone Senyar, it was whipped up by the north-east monsoon and a concurrent typhoon brewing near the Philippines.

The region is currently experiencing the north-east monsoon season, when winds blow mainly from the north and north-easterly direction.

During this season, monsoon surges are common. These surges refer to gushes or bursts of cool winds that flow from the Asian continent towards the warmer waters of the South China Sea.

During a particularly strong monsoon surge, the air can retain its rotational tendency from where it originates, despite being near the Equator, said Dr Koh.

If that develops into a closed circulation known as the Borneo vortex – a spinning weather phenomenon over the South China Sea near Borneo island – there is a chance that the vortex may persist over the sea, with heat from the evaporating sea surface fuelling it, said Dr Koh.

If the storm continues to strengthen with stronger winds and rain, it can reach the magnitude of a cyclone, as was the case for Typhoon Vamei.

That typhoon, which started from a Borneo vortex, came within 50km north-east of Singapore and brought extreme winds, halting flights, toppling trees and dumping 10 per cent of the entire year’s rain in one day.

Dr Koh noted that a published study had estimated the chance of a Vamei-like storm forming about once in 100 to 400 years.

Senyar was not sparked by a Borneo vortex, but was whipped up by a mass of circulating air from a monsoon surge in the northern part of the Strait of Malacca around Nov 21.

The formation of Cyclone Senyar was also influenced by another storm brewing in another part of the South China Sea

Dr Koh, who is also an adjunct associate professor at the National University of Singapore’s physics department, said: “It is a fact that when two cyclonic storms are within about 1,500km of each other, they interact significantly and modify each other’s trajectory.

“This interaction is not unlike the Earth and Moon orbiting around their common centre of gravity.”

The stronger Koto swung the weaker Senyar south-eastward along the Strait of Malacca, allowing Senyar to sustain itself and even intensify at times by the energy supplied by evaporation from the warm seawater, he added.

What else is driving the deadly storms sweeping through South-east Asia?

The floods across the region were caused by multiple factors.

The monsoon surge, and then Senyar, brought much rain leading to floods in southern Thailand, northern Peninsular Malaysia and northern Sumatra between Nov 20 and Nov 27.

Meanwhile, the floods in the Philippines and Vietnam were caused by the more powerful Typhoon Koto.

By the morning of Dec 1, Senyar had dissipated, while Koto continued to move south.

However, the effects of flooding can persist even after the storm has passed, because rainwater soaked into the ground takes time to drain into rivers and flow to the sea, said Dr Koh.

He said that while Cyclone Senyar did not reach Singapore, the destabilisation it caused in the surrounding atmosphere brought intermittent heavy rainfall here for a few days.

How does climate change affect these cyclones?

Tropical cyclones are a natural weather phenomenon.

But climate change makes them more severe. This is because warmer oceans provide extra fuel – heat and moisture – for these tropical storms to intensify.

“As our climate changes, there is an added element of uncertainty in the future tendency of cyclonic storms in terms of their frequency, intensity and duration,” noted Dr Koh.

Reports by the UN climate science body, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, continue to reveal much uncertainty in South-east Asia, he added.

“Much research still needs to be done on the science of tropical storms, cyclonic or otherwise, especially in equatorial regions around the world,” said Dr Koh.

What makes tropical cyclones so harmful?

Climate science professor Ralf Toumi from Imperial College London, who has done studies on equatorial cyclones, said such events are always significant and impactful because of their element of surprise and the extensive flooding that they bring.

He added that while tropical cyclones may not form near the Equator, a cyclone steered towards it could persist for several days despite weakening gradually.

“(This poses) a potential threat to vulnerable and unprepared communities in equatorial regions.”

People living in low-lying coastal areas and in mountain valleys are particularly vulnerable to flooding and landslides caused by persistent heavy rain of typhoons, said Dr Koh.

There is also a risk of wind damage to buildings and bridges that can lead to casualties.

What can I do to protect myself during a cyclone?

If you are in a shelter that will not withstand strong winds, flooding or a storm surge, leave for a safer location, advised the Government of Western Australia’s Department of Fire and Emergency Services.

Keep an emergency kit that has medication, food and water.

Charge devices like mobile phones if you have some time before a cyclone hits, in case of power outages.

During a cyclone, stay away from doors and windows. After the cyclone, do not walk, drive, ride, swim, boat or play in flood waters.