S’pore mulls over sixth desalination plant, possibly underground, to boost water security

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

The Keppel Marina East Desalination Plant in Singapore.

PHOTO: KEPPEL CORPORATION

SINGAPORE - The Republic is studying the feasibility of building a sixth desalination plant underground to boost the security of its water supply.

National water agency PUB said on Dec 26 that a tender has been called for a study for such a facility.

The study, which is expected to take about 10 months to complete, will assess the viability of a plant that can treat both seawater and fresh water like the Keppel Marina East Desalination Plant

Such flexibility to switch between both kinds of water would enhance the resilience of Singapore’s water supply to the weather, PUB said in its statement.

Tender documents revealed that PUB is studying the option of developing the plant fully underground.

This option would mean more space on the surface for recreational facilities or other infrastructure to be co-located at the same site.

The fully underground desalination plant would be “pushing the envelope beyond what was implemented for (Keppel) Marina East Desalination Plant”, PUB said in the tender documents.

The Keppel Marina East Desalination Plant, which opened in February 2021, has treatment facilities underground, and a green rooftop constructed for community recreation.

PUB said a site has been safeguarded for the potential plant – with its size estimated based on previous desalination plants built here – but did not reveal its location.

Previous plants have occupied between 2.7ha – roughly the size of 3½ football fields – and 14ha of land.

Mr Ridzuan Ismail, director of PUB’s policy and planning department, said more details of the site will be shared after the feasibility study is completed.

The documents noted that nature groups could be engaged to shape the scope of an environmental impact assessment for the site at a later stage of the study. These assessments are typically implemented for development projects close to sensitive nature areas.

Should an assessment be required, PUB will study the impact of brine discharge on the surrounding marine environment, said Mr Ridzuan.

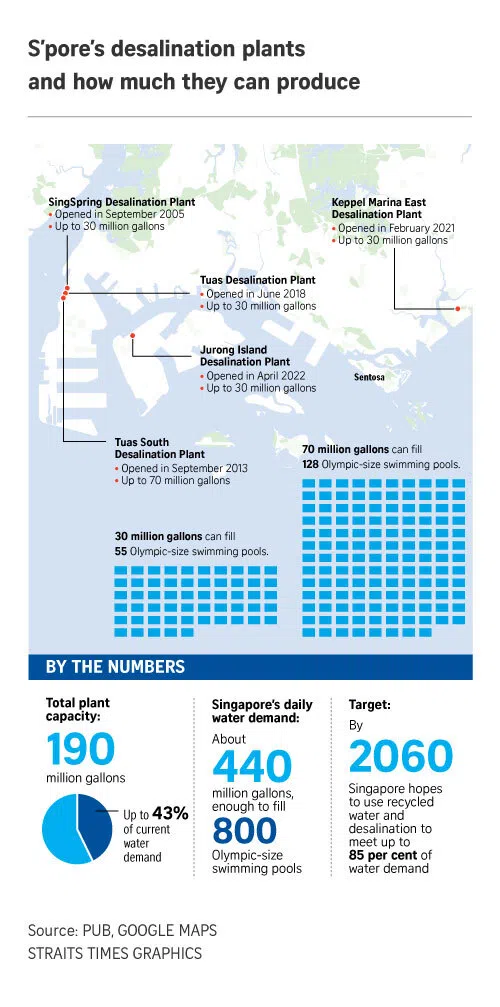

Singapore’s five existing desalination plants are located in coastal areas in Tuas, Jurong Island and Marina East.

Mr Chew Men Leong, president of the Singapore Water Association (SWA), said desalination plants are typically placed near the coast, as doing so allows efficient seawater intake and discharge, as well as minimal pumping energy and environmental impact.

Given Singapore’s land constraints, future plants will likely be built on multi-use or highly optimised land parcels, such as industrial or utility zones where infrastructure synergies can be achieved, added Mr Chew, who leads the association representing 350 members of the water industry.

For instance, the Jurong Island Desalination Plant is integrated with Tuas Power’s Tembusu Multi-Utilities Complex, making it about 5 per cent more energy-efficient than conventional desalination plants.

Both facilities share seawater intake and water-discharge facilities. The electricity generated in the Tuas Power complex also goes to the desalination facility.

These features result in annual energy savings sufficient to power nearly 1,000 HDB households.

PUB said that for the potential plant, it will be exploring multi-functional designs that maximise land use and lower the new plant’s footprint.

“This considers lessons learnt from existing desalination plants, such as incorporating higher multi-storey buildings and deeper basements to house treatment facilities,” the agency said.

The study will entail the development of three plant design options, and assessments on their technical feasibility and economic viability.

Apart from the underground design, the other two options being considered are a multi-storey building similar to Tuas South Desalination Plant, and a plant with a lower land footprint due to multiple levels and a deeper basement.

The study will also analyse the potential for worsening raw water quality in the future, and factor in any additional treatment processes required to cope with this impact.

Associate Professor Darren Sun Delai from NTU’s School of Civil and Environmental Engineering said that with Singapore’s mean sea levels projected to rise up to 1.15m by the century’s end, seawater is increasingly threatening to intrude into low-lying freshwater bodies and reservoirs, compromising drinking water quality.

“Warmer ocean temperatures lead to increased algae and plankton growth, which can lower the filtration efficiency of existing desalination plants or increase desalination pre-treatment cost,” he added, noting that 2024 was one of the hottest years on record.

The study marks a shift towards plants that treat both seawater and reservoir fresh water, said Prof Sun.

Assistant Professor Tan-Soo Jie-Sheng, NUS Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy’s incoming director of the Institute for Environment and Sustainability, said PUB’s study is part of a broader shift towards adapting infrastructure to climate change.

The global water cycle is increasingly out of balance, as rainfall patterns that were once relatively predictable are becoming more variable, he said.

“In South-east Asia, climate change is already manifesting in greater rainfall volatility, more intense droughts and floods, and rising temperatures that increase evaporation and water demand.”

Singapore relies on four sources of water, two of which are dependent on how much rain falls over the catchment area.

They are: Water imported from Malaysia’s Johor River, which makes up the bulk of water used here, and rain water captured in Singapore’s waterways and reservoirs.

But changing weather patterns due to climate change run the risk of disrupting the supply.

Prof Tan-Soo said: “This growing uncertainty underscores why Singapore must increasingly look towards weather-resilient water sources, such as desalination, as part of its long-term water security strategy.”

The two more weather-resilient sources of water are recycled used water – dubbed NEWater – and desalination.

The energy-intensive process of desalination produces drinking water by pushing seawater through membranes to filter out dissolved salts and minerals. Because of this, desalination is the most expensive way to produce water.

Prof Tan-Soo said a sixth desalination plant would further diversify Singapore’s water supply, strengthening resilience against climate-related shocks while meeting long-term demand growth and reducing reliance on any single source of water.

For Mr Chew, SWA’s president, the study creates an opportunity for the industry to evaluate and deploy next-generation technologies, from low-energy membranes that filter seawater to smart digital control systems.

“Singapore’s approach to desalination stands out globally for its emphasis on innovation, integration and efficiency, rather than scale alone,” he said, adding that the next plant can accelerate the adoption of emerging technologies.

Since desalination was first introduced in Singapore in 2005, the island-state has built five desalination plants.

Earlier in December, PUB announced that Keppel Infrastructure Trust will continue operating Singapore’s first large-scale desalination plan for another three years. The service contract for the SingSpring Desalination Plant had been due to expire in 2025.

PUB previously said the plan is for recycled water and desalination to meet up to 85 per cent of Singapore’s future water demand, which is set to almost double by 2065.

Currently, Singapore’s daily water demand is about 440 million gallons, which is sufficient to fill 800 Olympic-size swimming pools.

The Republic’s desalination plants can meet up to 43 per cent of current water demand, with a total capacity of 190 million gallons of water.

Total water demand in Singapore is projected to rise with industrial growth, especially with the push for semiconductor plants and data centres here. In 2065, non-domestic demand is expected to account for more than 60 per cent of water demand, up from the current 55 per cent.

Meanwhile, household water consumption has also inched upwards. In 2024, each resident used 142 litres of water a day, up from 141 litres in 2023. This was comparable to usage in 2017.

Under the Singapore Green Plan 2030, the goal is to reduce household water consumption to 130 litres per person a day.

Correction note: An earlier version of the story used the wrong designation for Assistant Professor Tan-Soo Jie-Sheng. We are sorry for the error.