Can Singapore keep the lights on while cutting carbon from its energy sector?

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Singapore has ramped up its target for importing clean energy, and is investing heavily in emerging technologies that could supply the country with carbon-free electricity.

ST PHOTO: CHONG JUN LIANG

SINGAPORE – In 2022, a report commissioned by Singapore’s Energy Market Authority (EMA) came to the bold conclusion that it was feasible for the country’s energy sector to reach net-zero emissions

This may not be a startling proclamation for other countries, such as Sweden and Canada, which have plenty of renewable resources that enable them to rely less on fossil fuels to keep their lights on.

But 95 per cent of Singapore’s electricity needs are now met by burning natural gas, a fossil fuel. This sector contributes almost 40 per cent of the country’s total emissions, so bringing this down to net-zero will not be easy.

Yet, despite the geopolitical headwinds that have caused other countries to temper their expectations for going green, Singapore’s commitment to decarbonising its energy sector has not wavered.

There are silver linings globally too. In 2023, countries made a commitment at UN climate conference COP28 to triple their renewable energy generation capacity

Ahead of Singapore International Energy Week in end-October, where power sector decarbonisation is expected to be an issue discussed, The Straits Times speaks to experts on the Republic’s journey to greening its energy supply, and the challenges that lie ahead.

Shifting motivations

Since 2022, the case for transitioning the energy sector away from fossil fuels towards cleaner sources has remained, although the motivating factors have changed, say experts.

In the period following the Covid-19 pandemic, a key focus was sustainability, as countries sought to restart their economies in a greener way.

But Ms Lisa Sachs, director of the Columbia Centre on Sustainable Investment, said that shifting to low-carbon energy is no longer just about tackling climate change.

It is also pivotal for key economic sectors that will increasingly require low-carbon energy to be globally competitive, she told ST.

One example is the rapid advancement of artificial intelligence and growth of data centres, which have driven up electricity demand significantly around the world.

An International Energy Agency (IEA) report released in April projected that electricity demand from data centres worldwide is set to more than double by 2030 to around 945 terawatt-hours (TWh) – slightly more than the current entire electricity consumption of Japan.

“Whether it is through regulation or customer preferences, there is an increasing demand for low-carbon products and low-carbon intensity goods and services,” said Ms Sachs, citing examples of data hubs and industrial corridors which increasingly need low-carbon energy to stay competitive.

While the US, China and Europe are projected to remain the largest regions for data centre electricity demand over the coming years, IEA said that other regions like South-east Asia – where electricity demand from data centres is expected to more than double by 2030 – are experiencing strong growth in data centre development.

Greening data centres can have economic advantages, such as helping businesses save costs in the long term.

An Ember report published in May found that despite high upfront capital costs, greening data centres can lower long-term costs due to lower power usage and less exposure to fossil fuel price volatility. This can be done via improving energy efficiency of the centres and using solar and wind power.

Costs of some renewable energy sources have also been falling.

The average cost of solar energy in 2024 was 41 per cent cheaper than the lowest-cost fossil fuel alternatives, according to the International Renewable Energy Agency.

Moreover, new financial mechanisms have also been developed to provide an economic incentive for decarbonisation.

Singapore, for instance, is piloting a new class of carbon credits

When a coal plant is closed early, some planet-warming emissions are prevented from being released. These “savings” can be sold as carbon credits to emitters.

Many South-east Asian economies are powered by coal – which is the largest source of carbon emissions globally. But many of the region’s coal plants are young, and it makes little financial sense to shut them down ahead of time – unless transition credits are factored in.

Such tools further promote the energy transition, while providing an economic incentive for this.

The other key concern among countries, including Singapore, that continues to drive the energy transition is energy security.

Mr Beni Suryadi, senior manager for Asean Plan of Action for Energy Cooperation and Strategic Partnerships at the Asean Centre for Energy, said that the global energy crisis in 2022 could have driven Singapore to diversify its energy mix further, reducing exposure to global fossil fuel price swings.

Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022

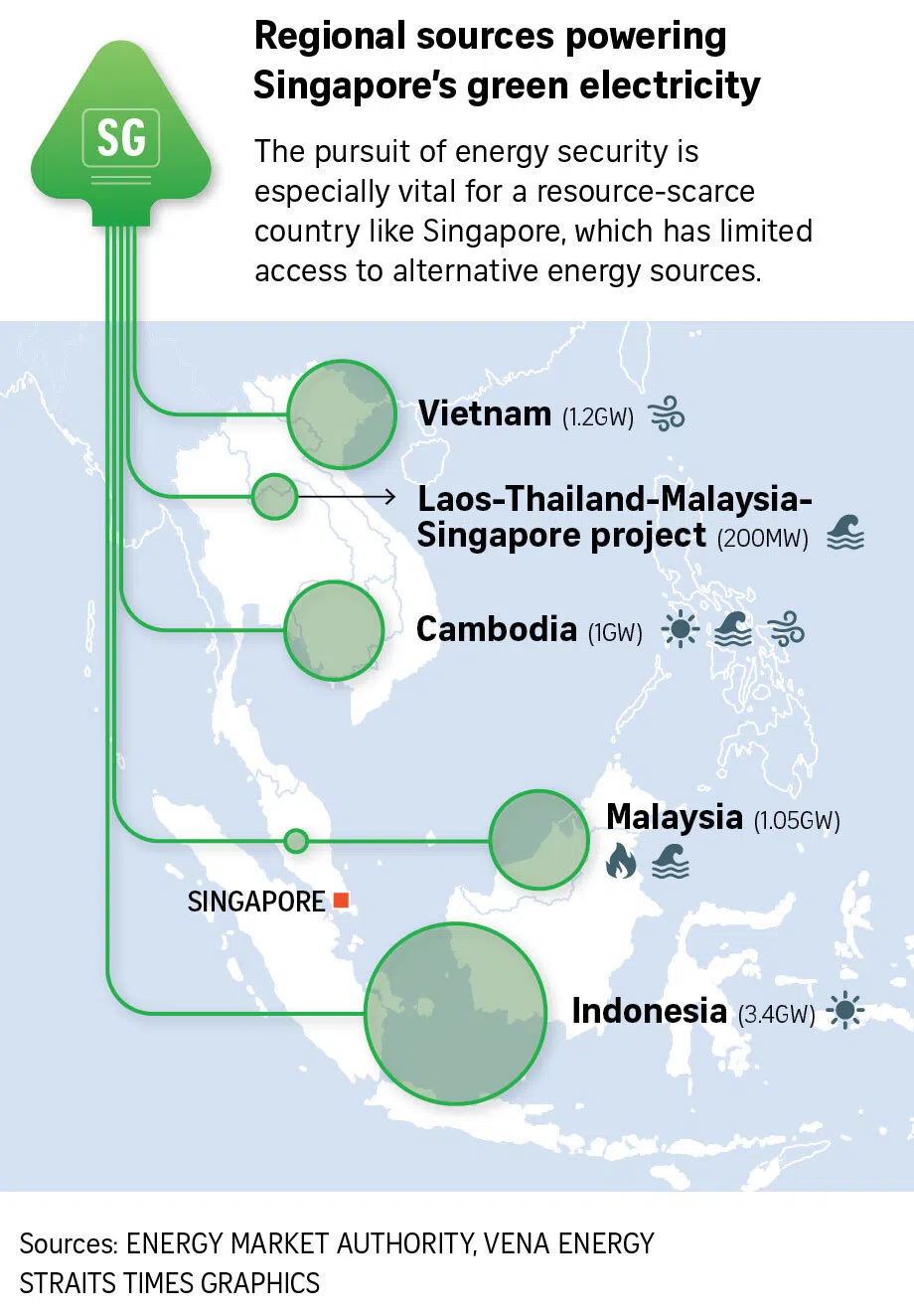

The pursuit for energy security is also especially vital for a resource-scarce country with limited access to alternative energy like Singapore.

This is where the Asean power grid – which will allow countries to share renewable energy resources – could help countries in the region diversify their fuel mix.

Singapore is banking heavily on this.

In September 2024, Singapore raised its low-carbon electricity import target

Mr Suryadi said: “Singapore has placed regional power connectivity at the centre of its transition strategy – developing cross-border interconnections to import renewable electricity from neighbours, alongside investments in domestic solar and storage.”

Dr Sung Jinseok, research fellow at NUS’ Energy Studies Institute, said the Asean power grid also has other economic advantages that add to the economic case for its development.

A US-Singapore study on energy connectivity in South-east Asia released in 2024 had assessed that the grid can generate US$2 billion (S$2.6 billion) annually

Compatibility with net-zero goals

Dr Tan See Leng, Singapore’s Minister-in-charge of Energy and Science & Technology, told ST in an interview in July that renewable energy imports hold the most promise

But he also said that the country will also be exploring all possible options in its energy transition, to ensure its energy needs are met in a sustainable, resilient and cost-effective way.

This includes investing in emerging technologies

These technologies, however, are all associated with their own uncertainties, and it is not clear when any of them could become commercially viable. If some of them only become deployable after mid-century, that would make their contribution to the net-zero by 2050 target less likely.

Dr David Broadstock, partner at the economic consultancy The Lantau Group, noted that Singapore was “keeping all sensible options open until there is better clarity on which will be the most sensible pathway to fully commit to”.

For instance, he noted that hydrogen still has some ways to go to reach mainstream commercial viability, while nuclear energy presents an emotive pathway with regard to public opinion. Other options like geothermal energy, provided by underground heat sources, have an unknown potential supply level.

But experts noted that the Asean power grid, if built up using already available and commercial technologies like wind and solar, allows countries to start taking action now.

Mr Robert Liew, director for renewables research for the Asia-Pacific (excluding China) at energy consultancy firm Wood Mackenzie, observed that there is increasing interest in developers to export renewables to Singapore due to high power prices compared to other Asia-Pacific markets.

The Asean grid was first mooted in 1997, but considerable progress on this front was made only in recent years.

In 2021, Singapore said it plans to import around 30 per cent

This helped pave the way for the electricity import pilot of the Laos-Thailand-Malaysia-Singapore (LTMS) power integration project

EMA has since issued conditional approvals to 11 projects to import low-carbon electricity from Australia, Cambodia, Indonesia, Vietnam and Malaysia.

The way forward

Despite the progress made on the Asean power grid so far, many deals still centre around bilateral agreements

Mr Dave Sivaprasad, the South-east Asia lead for climate and sustainability at consultancy Boston Consulting Group, noted that Singapore’s commitment to 6GW of electricity imports provides “strong market signals” that generate interest from regional green power developers.

This could contribute to catalysing bilateral and regional grid investments, as well as transboundary commercial arrangements.

But for a regional grid to take off, other countries also need to be willing to participate.

One oft-cited challenge is the need to establish mutually accepted codes and standards, as well as a market and governance framework for regional power trade. Another obstacle is the development of the infrastructure needed to connect the national power systems of different countries.

There is currently a low appetite among private sector players to fund grid infrastructure – such as electricity interconnectors between countries – due to the perceived high risks and large upfront costs

This is where the government-linked company Singapore Energy Interconnections (SGEI), which was set up in April

With its role to invest in, develop, own and operate interconnectors, it could help to increase investor confidence and attract new funding to help accelerate the transition.

When queried on its progress to date, an SGEI spokesperson told ST on Oct 19 that it is in discussions with several parties on the development of new interconnections. This includes a joint development agreement with Malaysia’s Tenaga Nasional Berhad and SP Group, announced at the sidelines of the Asean Ministers on Energy Meeting in Kuala Lumpur on Oct 17.

The spokesperson added: “This was to conduct a detailed feasibility study on a second power interconnection between Singapore and Malaysia.”

But while importing clean energy may be the most feasible option now, Singapore still has to keep an eye on which emerging technologies would be most suitable to help diversify its energy mix in the future.

Dr Victor Nian, founding co-chairman of independent think-tank Centre for Strategic Energy and Resources, said that while some technologies like nuclear energy and hydrogen may seem like a “distant choice”, Singapore needs to continue investing in them today so that informed decisions can be made as soon as these solutions become appropriate for deployment in the city-state.

Dr Tan, Singapore’s Minister-in-charge of Energy and Science & Technology, has also said that even if Singapore cannot be a first mover in some of the technologies, it wants to be the fastest adopter.

Singapore is continuing to move on this front.

It recently appointed consultancy firm Mott MacDonald in September to study the safety and feasibility of nuclear technologies

A second discovery of high temperatures underground in northern Singapore reported by ST in July gave a glimpse of the potential of using geothermal energy

The Government is also working with an industry consortium known as S Hub to study the feasibility of aggregating carbon emissions

Looking ahead, experts say more developments can be expected in these emerging technologies as global investments grow, pilot projects scale up and costs decline with innovation.

When it comes to keeping the lights on in a carbon-free way, Singapore faces the same challenges that many other countries face – how to balance its climate commitments with energy security and affordability.

And this will require the country to start taking action today, by investing in already available technologies such as renewables, while monitoring emerging areas.

“For Singapore, progress will depend on forging strong international partnerships for clean fuel imports, investing in local projects such as hydrogen-ready power plants, and building the regulatory and technical expertise needed to safely adopt nuclear and other advanced technologies when they become viable,” said Professor Chan Siew Hwa, co-director at Energy Research Institute @ NTU.

But Singapore’s small size could also help it be a leader in the global search for answers.

Mr Sivaprasad said that the nation’s smaller scale allows for a coordinated national approach on net-zero, enabling more effective coordination and strategy execution.

“Execution and implementation over the coming decade will be critical to our ultimate success in achieving net-zero,” he said.

Clarification note: The story has been updated with a response from SGEI.