The next steps to learning for life

Education Minister Ong Ye Kung has announced new measures to better equip Singaporeans for a future of lifelong learning. These include recalibrating the balance between academic rigour and a love of learning. This is an edited excerpt from his speech to heads of schools at the annual Schools Work Plan Seminar on Monday (Sept 24).

Sign up now: Get tips on how to help your child succeed

Change is a constant in education. Change is a constant in life. We do not change for change's sake. As we change, we are careful to retain the core strengths of our system to deliver students sound values and strong fundamentals in numeracy, literacy, and critical soft skills. The system is already well developed and I don't think we are in the building-up phase anymore. However, as it becomes more complex, we need to be clear-eyed that in this matured system, there are trade-offs within the system, and we must take sufficient bold steps to rebalance those trade-offs when needed.

In my speech at the Economic Society of Singapore, I stated four such trade-offs.

First, the balance between rigour and joy - how much robustness we want in the system and hard work we require from students, versus making learning fun and nurturing the joy of learning in our students. And we know that many of us realise education in schools is at risk of becoming too stressful and maybe some unwinding is in order.

Second, sharpening versus blurring of academic differentiation - how finely differentiated we want examination results to be as a tool for placement and admission, versus blunting the distinction of results between students so that we can gauge learning outcomes without encouraging an overly competitive culture in our schools.

Third trade-off, customisation versus stigmatisation - how our curriculum caters to students of different learning paces and learning needs, versus inadvertently stigmatising certain groups of students who are less academically inclined. Fourth, skills versus paper qualifications - the importance of attaining credentials such as Nitec certificates, diplomas or degrees, versus acquiring skills that make a person effective at the job.

The next phase of change in education will involve re-balancing these trade-offs effectively, decisively, and many initiatives are already under way.

In 1997, we developed the "Thinking Schools, Learning Nation" vision, to strengthen thinking and inquiry among students. During this earlier phase of change, we reduced curriculum content by about 30 per cent, enhanced teacher training and encouraged the sharing of best practices and ideas across schools.

In 2005, we embarked on the "Teach Less, Learn More" movement as a subsequent phase to further strengthen teachers' pedagogies. Our aim was to help teachers better engage students and develop their critical faculties through real-life learning experiences. Curriculum then was further reduced by 20 per cent, to create time and space for more active and independent learning.

"Thinking Schools, Learning Nation" was framed from a national and systemic perspective; "Teach Less, Learn More", from the teacher's perspective. Both remain relevant and important, but to help our students meet the challenges of an uncertain, fluid future, we must remember they are the ones that will face the future. We need to usher in a new phase of change - one that is framed based on the students' perspective.

LEARN FOR LIFE - THE NEXT PHASE

I call this phase of change - "Learn for Life"."Learn for Life" is a value, an attitude and a skill that our students need to possess. It also has to be a principal consideration in our school system.

Why has this become so important? In the past, Singapore attracted multinational corporations (MNCs) to set up factories and offices here. We were the world's leading producer of disk drives. We knew what kind of talent those MNCs needed, and we teach, we educate and we prepare our students well to fill up those defined job roles.

Today, the MNCs are putting their innovation hubs and R&D centres here. Start-ups are sprouting all over, hoping to come up with the next big thing. We are witnessing the advent of "lights-out manufacturing", where entire factories are automated. You step into it and you don't see anything, but in the background, you have personnel with different skill sets to design the system and ensure it hums along.

Today, you can check in and board the aircraft in Changi Airport Terminal 4 without interfacing with a single human, and that has totally redefined what a customer officer is supposed to do. These innovation centres, start-ups and automated environments are creating the jobs of tomorrow. We have some ideas but not definitive ideas of what these jobs will be; what are these jobs that our students are going to take up.

What we do know, however, is the shape of things to come. We know that our students need to be resilient, adaptable and global in their outlook. They must leave the education system still feeling curious and eager to learn, for the rest of their lives. These traits are not just adjectives that we tick off, one by one. It is a fundamental shift in our mindset.

I came across a recent article about how the author of the article, who is a middle-aged man, was trying to learn coding. I thought it explained the concept of lifelong learning quite well. It is really not about searching for the next course to attend and trying to use up the $500 SkillsFuture Credit.

Instead, it is about getting used to a state of discomfort. His key takeaway was not the technical coding skills that he picked up, but getting used to the feeling of constantly being inadequate.

So in the article, he described what a coding coach told him: "You need to get used to the idea of being out of depth all the time. You do not solve the same problem twice. You solve one and the next level is even more challenging and once again you feel inadequate. But there is a global coding fraternity that you must learn how to tap, and then you learn from one another, from that network."

I see this attitude among many elderly learners, who are obviously lifelong learners. Many do not know English well, and are not IT-literate. But they are motivated to learn to use the computer, the apps on their smartphones, and embrace e-payment to minimise their trips to the ATMs. It is uncomfortable for them, but I see the determination among these members of the Pioneer and Merdeka generations.

Once we recognise this broader objective of education, examination and grades are comparatively small milestones in the life journey of a child. The ability to score in an examination frankly may not matter very much later on in the life of a child.

BALANCE BETWEEN RIGOUR AND JOY

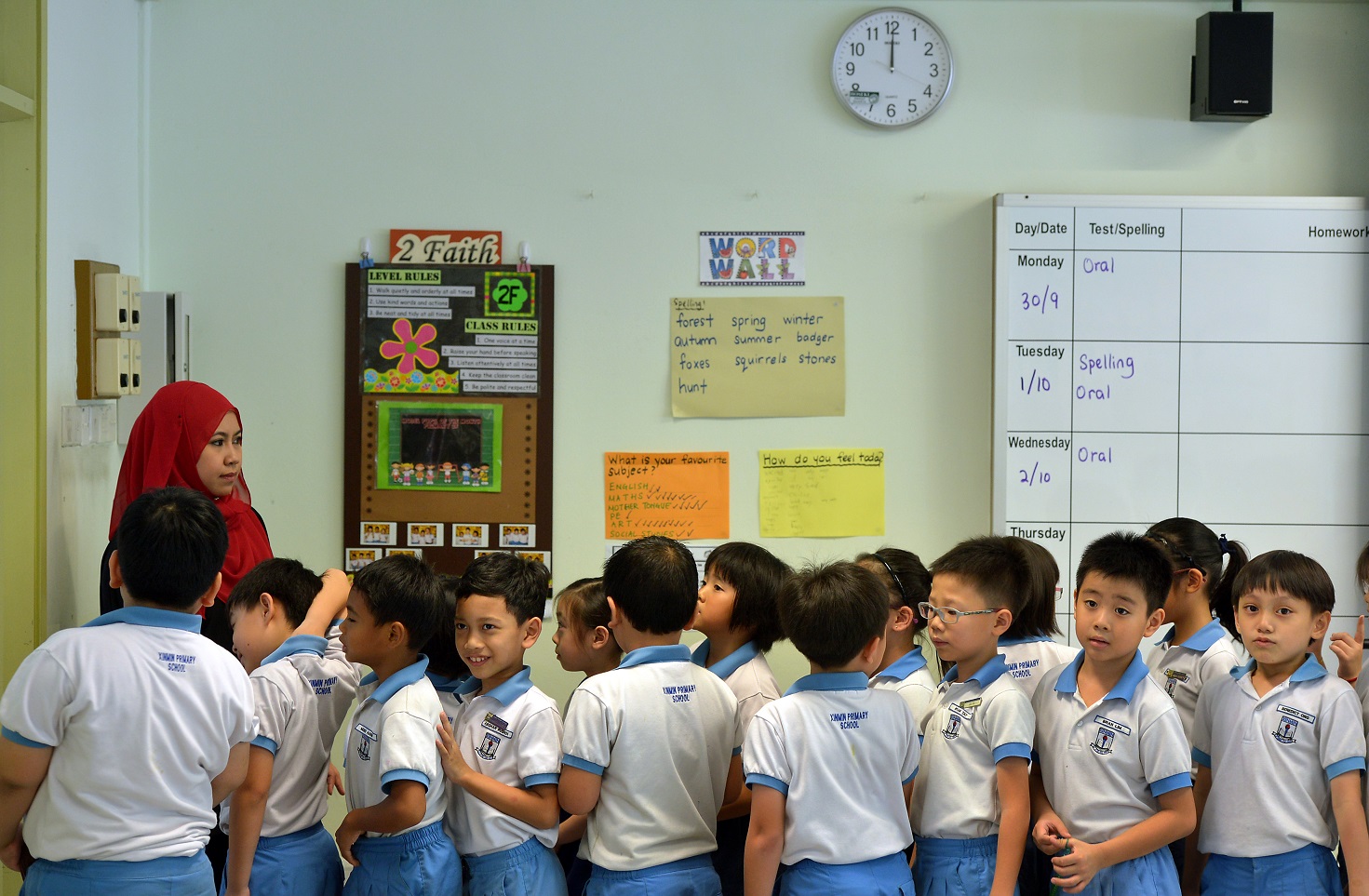

We know that students derive more joy in learning when they move away from memorisation, rote learning, drilling and taking high-stakes exams. Very few students enjoy that.

It is not to say that these are undesirable in learning; quite the contrary, they help form the building blocks for more advanced concepts and learning, and can inculcate discipline and resilience. But there needs to be a balance between rigour and joy, and there is a fairly strong consensus that we have tilted too much to the former. Our students will benefit when some of their time and energy devoted to drilling and preparing for examinations is instead allocated to preparing them for what matters to their future.

In doing so, we have a few considerations. First, there is little room for further cuts in curriculum. We have already done two significant rounds of reduction, in 1998 and then in 2005. Further reduction will risk under-teaching. What we should focus on is to curb effort inflation and review our assessment load and tuition load - both of which add to the repetitive and unnecessary effort of studying the same, or even less material, for the sake of scoring well in examinations.

Second, whatever time we may free up for the students, we must avoid the tendency to fill it up with extra practice and drills. Instead, treat this as curriculum time that we return to the schools, return to the principals and teachers, for better teaching and learning.

THE YUTORI CHALLENGE

Finally, we must be careful not to overdo the correction, and inadvertently undermine the rigour in our system. Japan offers us a very useful experience that we can learn from. In the 1990s, they implemented in their school system an initiative called Yutori. For those who know Japanese, Yutori means "relax".

The objective was to reduce rote learning and memory work, and redirect students to learning creativity and soft skills. But the move backfired - as Pisa (Programme for International Student Assessment) scores of Japanese students deteriorated, parents' anxieties went up, and students started to worry that they can't do well in the university entrance examinations. Hence the Yutori policy had to be unwound, and five years later, the government had to increase the curriculum content back and teaching hours back again.

While well intentioned, Yutori's objective was ahead of its time, and its implementation, not helped by a rather inappropriate name, was perceived as too drastic a move.

We can learn from Japan's experience. It is an instructive example, demonstrating the challenge we might face as we recalibrate the balance between joy and rigour within our system.

REDUCTION OF ASSESSMENT LOAD

Given these considerations, we decided to take the approach of reducing school-based assessment.

We have succeeded in doing this before. MOE removed mid-year examinations and year-end examinations in P1 from 2010. For P2 students, we further removed the mid-year examinations.

As a result, we reduced the stress for lower primary students. Today, everyone - teachers, students, parents - have got used to not having to worry about examinations in P1 and for most of P2. Academic results and rigour have not been affected. We will build on this good work. We know that teaching and learning comprises three important components - curricular goals and content, pedagogy and assessment, and together they form a strong triangle. Today, the three components are not balanced. As we overemphasised assessment, we inadvertently reduced the time available for schools to focus on teaching and learning. We will therefore make another significant move, and reduce school-based assessment load by 25 per cent in each of the two-year blocks in primary and secondary schools.

We will remove all weighted assessments for P1 and P2 students. This means that in addition to what had been removed, we will further remove year-end examinations for P2. Schools will also not count any assessments towards an overall score for P1 and P2.

We need to recognise that students go through different stages of learning: from lower to middle to upper primary, and then to lower secondary and eventually, upper secondary. Each stage requires a significant transition and pupils need an adequate runway to adapt to the new demands.

To help students build their confidence and develop an intrinsic motivation to learn during the transition, we should be less hasty in testing and examining students during these critical years. Hence, we will also remove the mid-year examinations at P3, P5, S1 and S3.

Schools and parents need not worry about the pace of change being fast. We will implement these changes in stages.

In 2019, we will remove all weighted assessments in P1 and P2, as well as the mid-year examination in S1. The removal of mid-year examinations at P3, P5 and S3 will be carried out over two years, in 2020 and 2021.

There is nothing wrong with having examinations and class tests, but we need to use them in suitable quantities. They are part and parcel of teaching and learning. They help teachers gauge their students' learning, and students to gauge their own learning along the way.

By all means, use formative tools such as worksheets, class work and homework to gauge learning outcomes and the strengths of each child. These are not high-stakes tests or examinations, which result in substantial loss of curriculum time. Our focus is to return the curriculum time to the schools to free up learning and teaching.

BETTER TEACHING AND LEARNING

How will these changes add up? They will free up about three weeks of curriculum time every two years. This time is now returned to the schools and teachers, and with it, the flexibility to pace out teaching and learning so as to avoid a mad rush to complete the syllabus to prepare for tests and examinations. I hope schools will use the time well, for example, to conduct applied and inquiry-based learning.

In applied and inquiry-based learning, our students observe, investigate, reflect and create knowledge. And that naturally will take up more time.

For example, we can teach a child the area of a field is length multiplied by breadth. Go memorise the formula and take the tests. It can be done in a short time. But in an inquiry approach, we will ask the child, how do you find out the area of the field and have them discuss and brainstorm.

Some may decide drawing those squares to fill up the field and count them. Others may have their ingenious methods. After that, the teacher may take them out to the school field to measure the length and breadth of the field, before allowing the students to discover that length multiplied by breadth equals area.

In art, we do not just ask students to draw something - when I was in primary school, my teacher asked me to draw a cat or apple and I would just draw. Now, we show them masterpieces, ask them what they observe, and why the artist had expressed himself that way. We ask them what do you think Monet is thinking of, what do they think Van Gogh is thinking of. We ask them what they want to express, how to express, and from there conjure their artistic creation.

Through the inquiry approach, students think and internalise concepts. The lessons are fun and more applied in nature. They are more likely to remember and enjoy the lesson, even though that could take up more time. The learning outcomes are better, and these are backed up by research, and also by ancient wisdom.

With the time and space created from reducing the assessment load, we hope teachers will leverage effective inquiry-based pedagogies, to enhance students' learning experiences.

Our decision to reduce examinations is also backed by the experiences of trailblazers. One such school is Woodlands Ring Secondary School. It has removed mid-year examinations for S1 to S3 students since 2012. It has gone beyond what MOE is stipulating today, without affecting its students' O-and N-level examination performances.

With the time freed up, the school can dive deeper into the curriculum at a pace that suits each learner. For example, the mathematics department designed a learning trail for S1 students to extend their learning beyond the classroom. The school has received positive feedback from the teachers, students and parents, that the students are becoming more self-directed and motivated.

Henry Park Primary School has removed term assessments in terms one and three for P3 to P6 students since 2014, and channelled the additional time into inquiry-based learning and student-initiated investigation.

CHANGES IN REPORT BOOKS

We will also make adjustments to the Holistic Development Profile, or more commonly known as the report book, to better reflect a student's progress in learning, and to discourage excessive peer comparison. These adjustments will also help to reduce test anxiety.

For P1 and P2 where there will be no more weighted assessments, we will use qualitative descriptors instead of marks to inform parents of their child's progress. For other levels, where marks are available, they will be reflected as whole numbers instead of decimal points, which are an unnecessary precision.

We will also remove certain academic indicators, such as the students' class and level positions. I know that "coming in first or second", in class or level, has traditionally been a proud recognition of a student's achievement. But removing these indicators is for a good reason, so that the child understands from a young age that learning is not a competition, but a self-discipline he needs to master for life.

Notwithstanding, the report book should still contain some form of yardstick and information to allow students to judge their relative performance, and evaluate their strengths and weaknesses.

PARENTS AND TUITION

I am confident that the students who are experiencing the changes first-hand will be able to see the value in what we are doing. However, for this shift to succeed, we will also need to bring in the most important stakeholder - parents - on board. We will need to show parents that the reduction does not compromise on academic rigour. Instead, we are optimising the number of assessments students have to sit today for better results.

We must expect some things are beyond MOE's or the schools' control - such as parents comparing notes in their WhatsApp groups that often raise anxieties, and sending their children for tuition and enrichment. I have no intention to heed the calls to ban tuition. Parents do this out of care and concern for their children, and many do-gooders in the community conduct free or low-cost tuition to help weaker students cope with their studies, and that's a good thing.

But there are negative tuition stories too. During my school visits, sometimes I'll ask them - do you find it stressful in schools?

They will tell me "no", but that tuition is stressful. They are very tired on weeknights after school or on weekends, because their day is packed with many tuition classes. Worst, they find that learning is not fun as a result and lessons have taken over their days and weekends.

So there is room for parents to step back, give children space to explore and play. On MOE's end, there is also room for us to step back, review the way we have been involving and engaging parents in school life, and make the nature of partnership between parents and schools clearer.

CALIBRATED STRUCTURAL CHANGE

What I just talked about is a significant but calibrated structural change, to reduce effort inflation and to create a better environment for holistic development. It is part of our journey to constantly evolve and improve.

With the removal of one mid-year examination in every two-year block, teachers will not need to rush through the syllabus. This gives them the time and space to explore new areas, and try out more effective pedagogies. If we expect our students to learn through trying and failing and trying again, teachers should also embody this spirit and set a good example of lifelong learning and lead by example.

We have a strong and excellent teaching force, an advantage that not many countries enjoy.

If we harness the passion, creativity and dynamism of our teaching force, we can make bold and meaningful changes to prepare our students well for the future. This is our collective moral imperative.