Viewpoint: At S’pore’s Gen Z friendship festival, the most effective cure for loneliness was money

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Gen Z partygoers took over Funan mall on Aug 29 and 30 for a two-night-only sober party.

ST PHOTO: TEO KAI XIANG

Follow topic:

SINGAPORE – On Aug 29, thousands of Gen Z Singaporeans descended on Funan after dark for what organisers called “the biggest sober party in Singapore”.

Many of them packed into the mall’s basement foodcourt, where DJs spun R&B and hip-hop music. Upstairs, partygoers were jumping to Afrobeats and Brazilian funk at two other party zones: Mexican chain restaurant Guzman y Gomez and sportswear store Pas Normal Studios.

“I’ve never had any experience going to clubs,” said Ms Nur Diyanah, 21, who was there with her boyfriend, adding that the event exceeded her expectations.

Like many Gen Z gatherings, this was an event born almost entirely from social media hype.

One can trace its origins back to three Singaporean 21-year-olds going viral by posting about a house party in 2024.

This trio, the co-founders behind the coffee clubbing collective Beans&Beats, would spend the next year growing their events from small daytime parties in cafes into their Funan takeover.

Something that most revellers may not have realised, however, was that the party was just the evening finale to the For Real Fest, Singapore’s newest attempt at engineering a cure for modern loneliness. Its inaugural edition took place in 2024.

After experiencing it, this reporter found that the answer was not technological innovation or a radically new approach, but something far simpler: making things free.

Youth take on loneliness epidemic

Youth volunteers shared a variety of anti-loneliness solutions at the For Real Fest.

ST PHOTO: TEO KAI XIANG

Arriving at Funan on Friday at 6pm, four hours before the Beans&Beats afterparty was due to begin, I was not sure what to expect.

The For Real Fest advertised itself as “Singapore’s biggest playground for real connection”, a vague descriptor that drew only a modest early evening crowd.

Attendees I met variously described it as a Gen Z friendship festival, a way to teach young people to ditch their screens for real-world connections, and an unofficial successor to the government-run Social Development Network (SDN).

The SDN was an initiative of the Ministry of Social and Family Development (MSF), best known for being the government matchmaker and organiser of singles events before it pivoted away from the space in 2023.

The For Real Fest, while youth-led, is also supported by the MSF. Its organisers later clarified with The Straits Times that the event is not a successor to the SDN as it also focuses on non-romantic relationships.

The timing of the event felt apt. Loneliness was declared a pressing threat to global health

In Singapore, a 2023 survey of over 2,000 Singapore residents by the Institute of Policy Studies found that young respondents were more likely to report higher levels of social isolation.

Over 70 per cent of those aged 21 to 34 said they feel they lack companionship some or most of the time, the highest proportion of any age group.

“With social media, we’re really connected, but we really don’t know how to interact with one another,” one 21-year-old volunteer told me, summing up a view held by many attendees that technology was to blame.

Revellers donned light-up bracelets that could toggle between colours based on what they were looking for.

ST PHOTO: TEO KAI XIANG

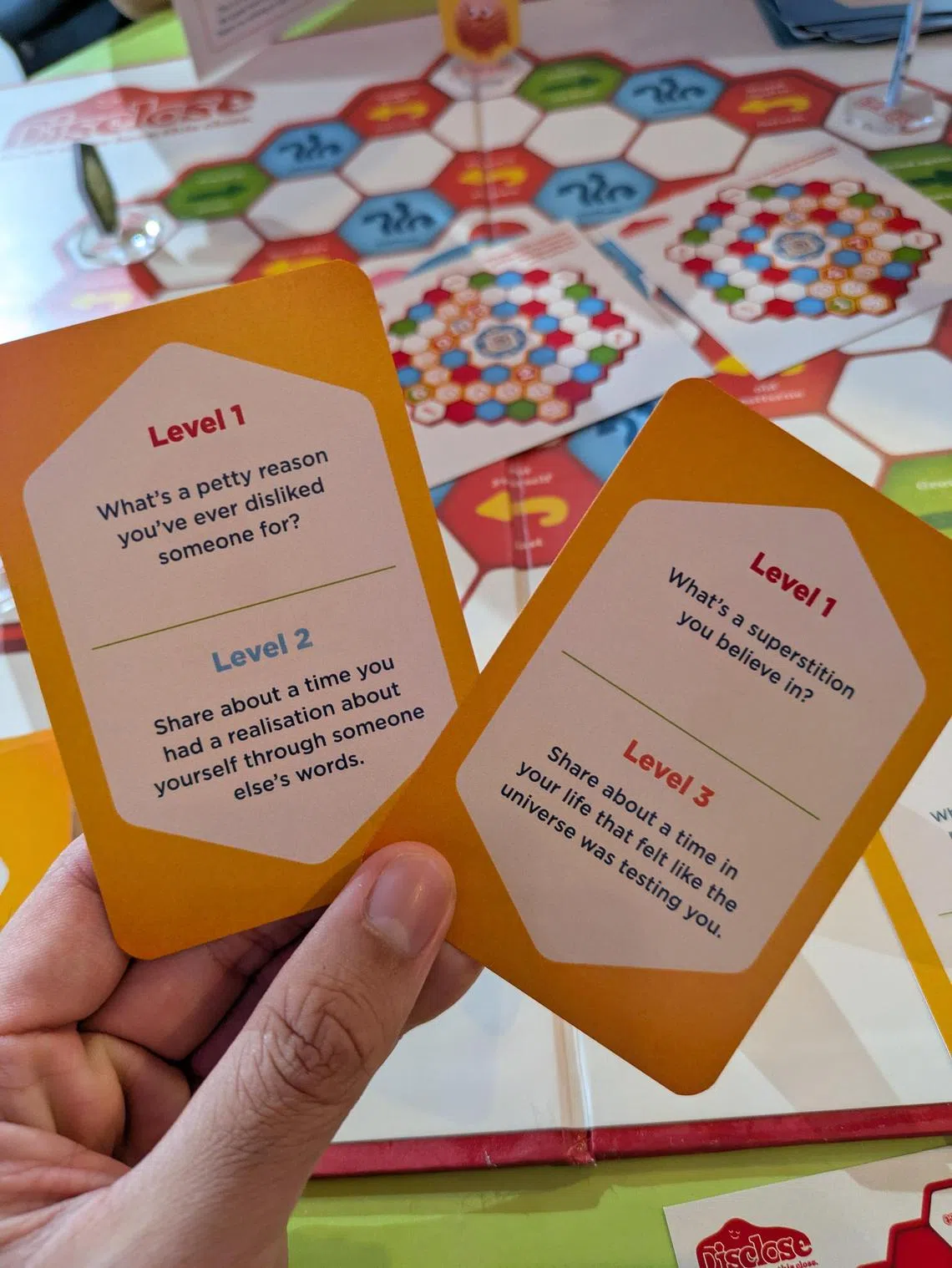

The festival’s response was a cavalcade of engineered solutions.

There were electronic light-up bracelets, which allowed people to toggle between green for “I want to connect”, blue for “I’m shy, please approach me first”, red for “open to love” and purple for “not in the mood”.

This was the device that had more than one attendee drawing parallels to an SDN singles event.

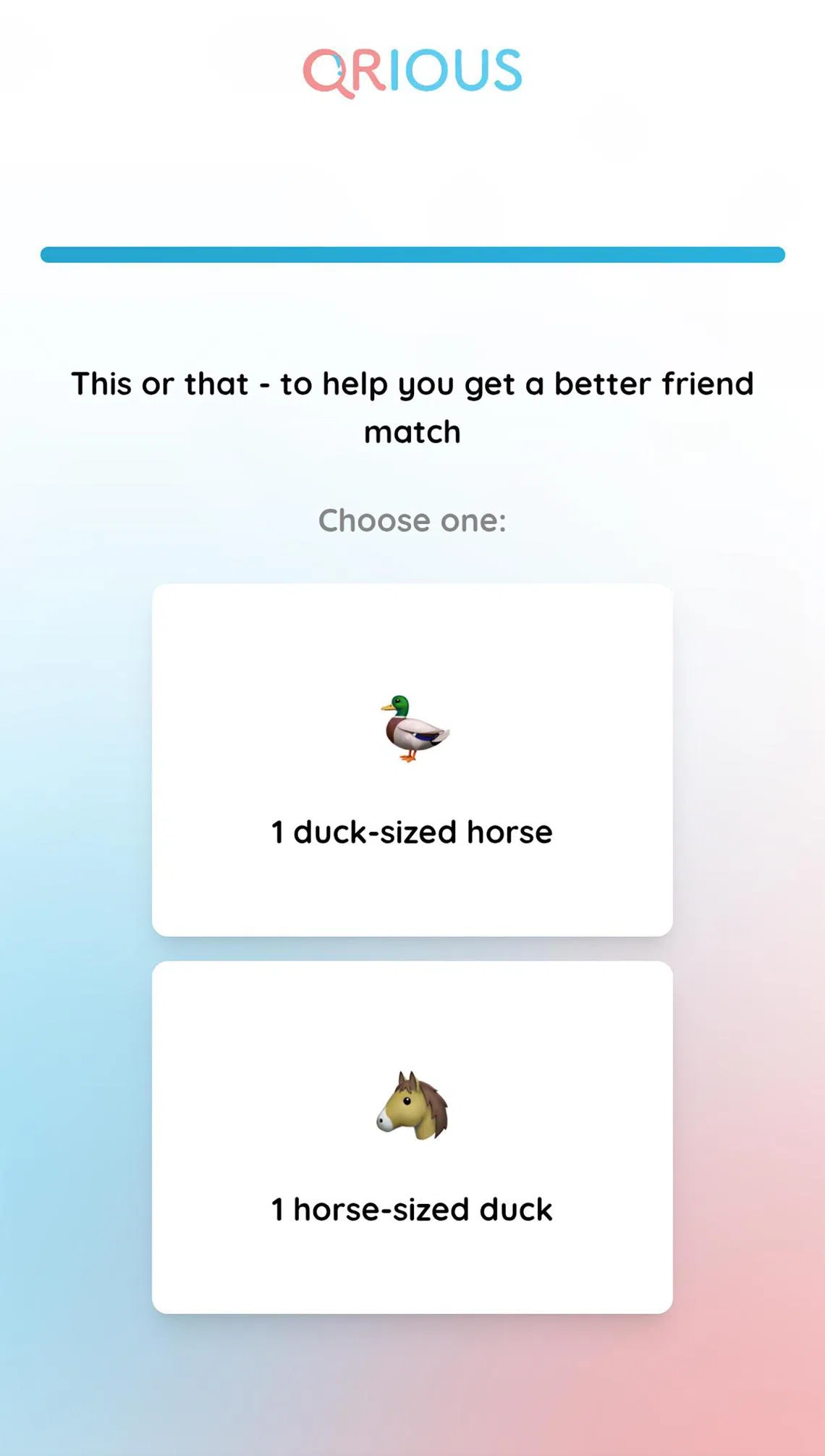

One of the anti-loneliness tech solutions on offer was a matching quiz one could access via QR code.

ST PHOTO: TEO KAI XIANG

One Gen Z volunteer told me she was inspired by an experience of going alone to a concert by K-pop singer Taeyeon to create QR codes that could be placed in cafes and concerts. These QR codes allow those too shy to make the conversational first move to match up with others after a short quiz.

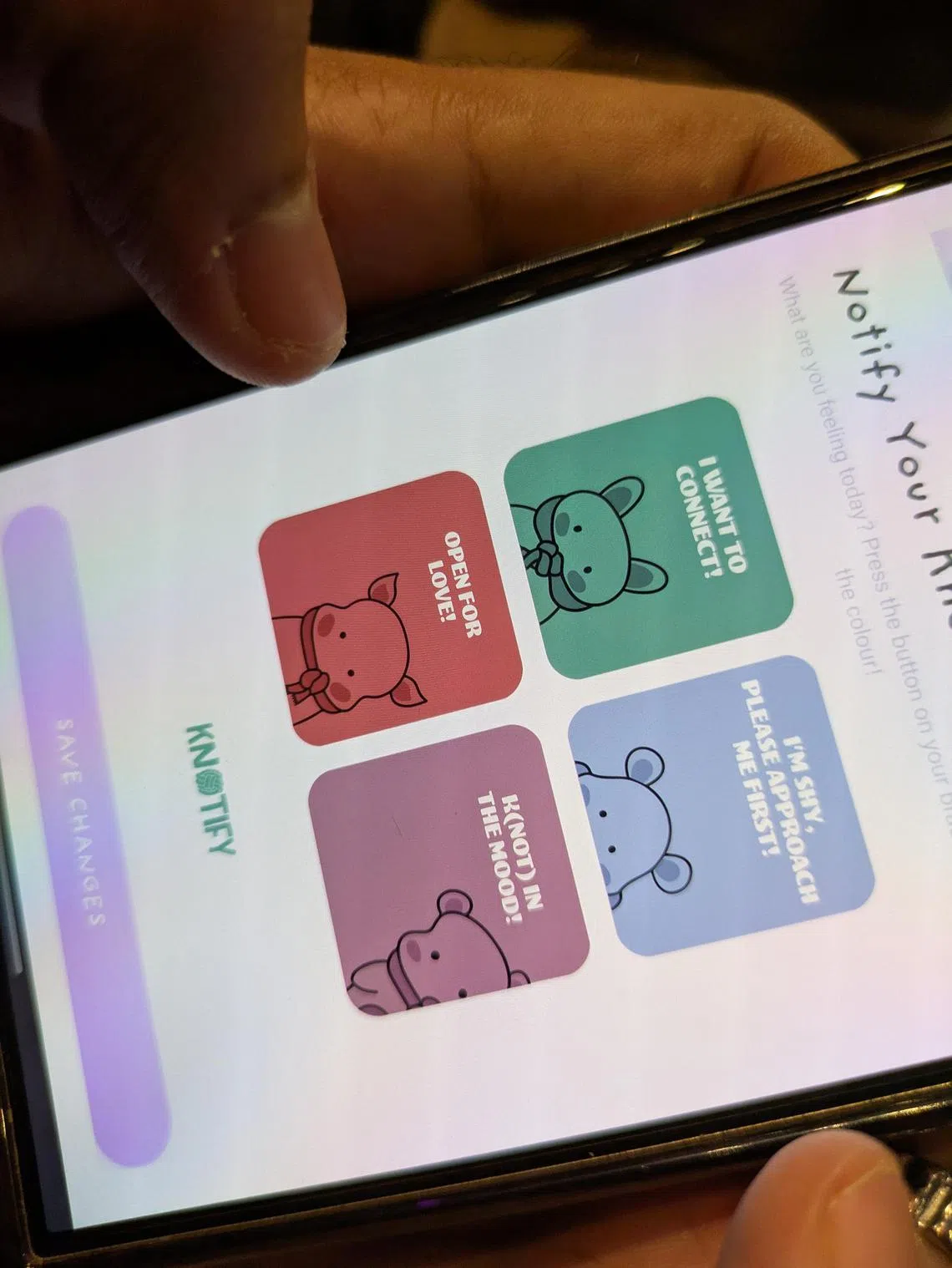

Another team of volunteers put together a board game, supported by fast-food chain McDonald’s, using intimate questions to fast-track friendships.

Playing with these new-fangled creations, I came away with a feeling that they were patches for symptoms of the loneliness epidemic, rather than the cause.

Instead, the festival’s best remedy for loneliness was a decidedly old-school one.

Free of charge

By 10pm, crowds of Gen Z Singaporeans – many of them young teens – were streaming into the mall, watching as a party collective transformed shops into dance floors. It took just minutes for each party zone to be packed to maximum capacity, with overflowing queues of eager partygoers that lasted until 1am, the festival’s closing time.

Inside, and despite the emphasis on sobriety, one could find all the usual party tropes.

Reluctant boyfriends being coaxed onto the dance floor by their girlfriends, mass chanting from revellers when their favourite song came on and the inevitable hoots as someone climbed atop a table to show off his or her moves.

There was also the stuff that made this a distinctly Gen Z space. At one point, a partygoer held their phone up high, with the brightness cranked up as they began opening booster card packs on their Pokemon trading card game app – drawing cheers from the crowd and many recordings likely destined for TikTok.

Beyond the noise, dozens congregated at whatever tables and steps they could find, creating that lively social atmosphere one typically encounters only in the underground spaces near the Esplanade, a frequent haunt of Singapore’s teens.

When young people have free space and events they can afford, spontaneous interactions emerge organically. The light-up bracelets, while a great party accessory, felt extraneous to that exchange.

Beans&Beats’ founders said they set out to create a new kind of “third space” for young people.

Third spaces refer to social settings outside of one’s home and work, such as parks and cafes. By that measure, it was a roaring success.

Much like many of Singapore’s much-beloved culture spots, what partygoers loved the most about the Beans&Beats party was that it made no business sense at all.

Without charging an entry fee, the event’s only – and optional – cost for partygoers was its sale of $10 cups of coffee.

Partygoers, many experiencing their first club-like environment, said the affordability created an inclusive atmosphere impossible to find at Singapore’s more price-prohibitive nightlife venues.

At the same time, the costs of crowd control, professional DJs and acoustically suitable venues likely exceeded what anyone could recoup from caffeine sales alone.

For context, Singapore’s nightlife woes do not stem only from young people feeling increasingly priced out by steep alcohol fees and late-night Grab fare, but also from how bars and clubs have long sustained themselves on alcohol revenues – something the trend towards sobriety calls into question.

It is unclear if any party collective, sober or otherwise, could do a similar event without significant support, receptive corporate sponsors like CapitaLand – Funan’s landlord – and a horde of eager volunteers.

In expensive Singapore, this feels like the recipe for any worthwhile community endeavour.

Money on my mind

Spontaneous connections emerged everywhere at Funan, where partygoers claimed whatever spaces they could find.

ST PHOTO: TEO KAI XIANG

Beyond the tech solutions and sober partying, the festival’s most poignant moment came during its film screenings by students of Lasalle College of the Arts.

In the documentary short Bahay Bahayan, student director Marienne Louise followed a Filipina in her mid-20s who has lost touch with her mother, who works as one of the Philippines’ millions of Overseas Filipino Workers (OFWs) – an isolating economic reality that shapes the lives of all their families.

Closer to home, short film Your Name On A Grain Of Rice depicts a day in the life of a schoolgirl on the financial assistance scheme.

From not being able to afford a smartphone or new shoes, to that uncomfortable twinge of envy and longing one feels when arriving at school sweaty and on foot while one’s schoolmate is dropped off in an air-conditioned car, the drama effectively captures all the invisible ways an underprivileged child faces exclusion.

More than just tugging on viewers’ heartstrings, these films also provide a window into the things that occupy many Gen Z minds today: money, financial anxiety and the fear that business as usual cannot solve the invisible gulf that has opened up between us.

A gulf that takes shape in the shortage of spaces where two people in Singapore can hang out in without spending a cent. And the emptying bookstores and cinemas as society increasingly takes culture to free and engrossing online alternatives like TikTok and YouTube.

Increasingly, life in Singapore is experienced in solitude.

To me, the For Real Fest is a lesson in how isolation for Singapore’s loneliest generation isn’t just about lacking social skills or screen addiction.

Friendships require infrastructure, and that infrastructure costs money. Creating free and accessible third spaces such as this, where young people can simply be, was money well spent.