Unveiling of Grand Egyptian Museum, an emblem of longevity and scale of Egypt’s civilisation

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Visitors gather around the statue of Ramesses II in the sun‑dappled Grand Hall of the Grand Egyptian Museum on the Giza Plateau, near Cairo.

PHOTO: GEORGES & SAMUEL – THE GS STUDIO

Follow topic:

Egypt’s ancient past is as much studied by schoolchildren in classrooms around the world as it is by expert Egyptologists.

Today, that shared wonder has finally found a home in the Grand Egyptian Museum (GEM) on the Giza Plateau, about 2km from the capital city of Cairo.

The museum’s main building, which opened to the public on Nov 1, features a massive atrium housing an 11m statue of King Ramesses II, 12 permanent galleries and a children’s museum.

Designed by architecture firm Heneghan Peng Architects – based in Dublin in Ireland, and Berlin in Germany – the museum is an emblem of the scale and longevity of ancient Egyptian civilisation.

The firm’s vision for the museum drew admiration and praise when it was chosen as the winner of a 2003 design competition by the Egyptian Ministry of Culture, which drew more than 1,500 entries from about 80 countries.

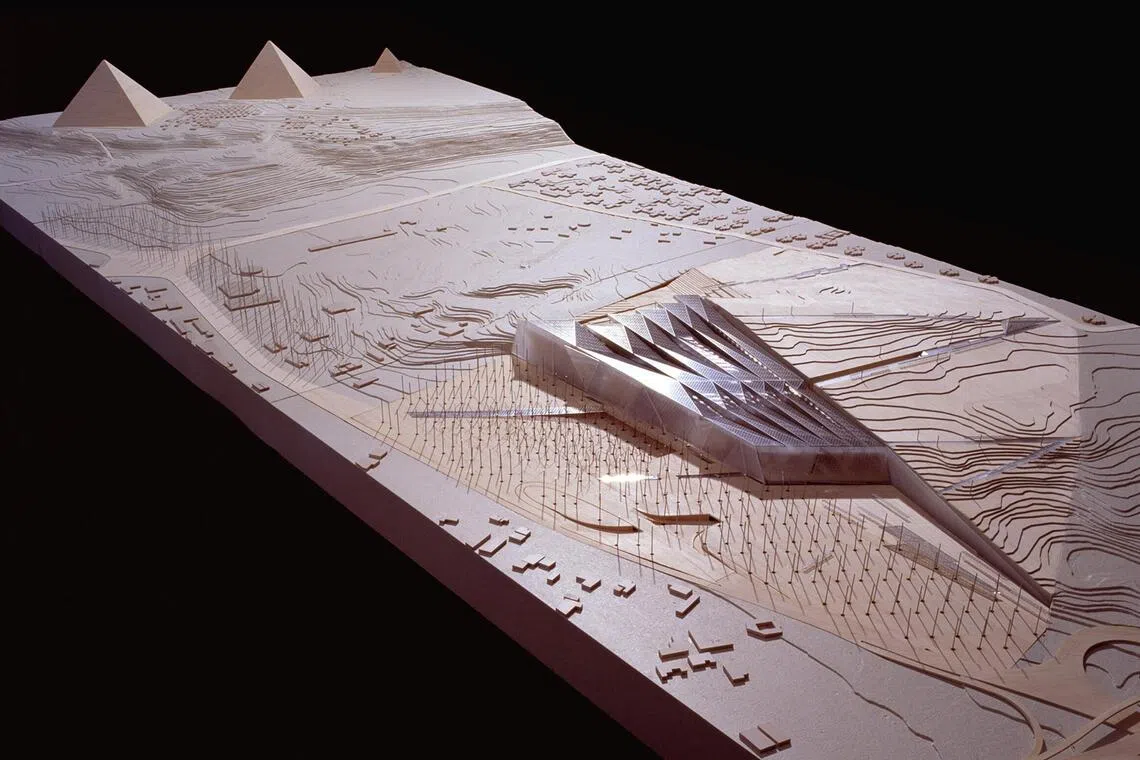

An architectural model of the Grand Egyptian Museum, set between Cairo and the Giza Pyramids.

PHOTO: HENEGHAN PENG ARCHITECTS

The architects designed the museum in direct relation to the positioning of the pyramids, thoughtfully bridging the gap between history and modernity.

The museum was planned in close alignment with the Giza Pyramids, its fan-shaped walls and sloping roof laid out along sightlines that point to the three pyramid peaks.

A grand six-storey staircase guides visitors through the different eras of Egyptian history.

PHOTO: GRAND EGYPTIAN MUSEUM

Inside, a grand staircase and a series of framed views lead visitors from cool glass-and-alabaster halls towards the pyramids’ silhouettes, quietly stitching together modern museum design with a view that dates back more than 4,500 years.

But it was an odyssey of more than 20 years from competition win to museum opening, stymied by financial shocks, the Arab Spring revolution of 2011, the Covid-19 pandemic and regional wars.

Enduring appeal of Boy King Tutankhamun

Today, the museum is billed as the largest in the world focusing on a single civilisation, spanning 500,000 sq m of desert land and built at a cost of more than US$1 billion (S$1.3 billion).

Its full completion was marked by the official opening on Nov 1, which coincided with the unveiling to the public for the first time of the entire collection of the Tutankhamun gallery, which comprises more than 5,000 artefacts.

The golden burial mask of Egyptian pharaoh Tutankhamun on display at the museum.

PHOTO: REUTERS

The burial mask of Tutankhamun is one of the museum’s most enigmatic draws.

It is described by Egyptologists as the pinnacle of Egyptian goldsmithing, showcasing two sheets of high-karat gold, about 54cm tall and weighing more than 10kg. It is inlaid with lapis lazuli, quartz, obsidian, turquoise and coloured glass for the headdress, collar and facial details.

A child looks at the golden coffin of ancient Egyptian pharaoh Tutankhamun.

PHOTO: REUTERS

Tutankhamun lived around 1341 to 1323 BCE. He ruled Egypt from about 1332 to 1323 BCE, about 3,300 years ago.

Also called the “Boy King”, he became pharaoh when he was about nine. He ruled for roughly nine years before dying around the age of 19, probably from a combination of a serious leg fracture and malaria rather than a single clear cause, according to Encyclopaedia Britannica.

If one looks closer at his mask, the eyes seem to turn reddish towards the outermost ends. A masterpiece of Egyptian inlay work, it combines different materials to create a life-like appearance.

The whites of the eyes are inlaid with quartz, while the pupils are made from obsidian, a naturally black volcanic glass.

The eyelids and eyeliner are outlined and inlaid with lapis lazuli, a deep blue semi-precious stone. The reddish corners of the eyes are achieved using carnelian inlays which catch the light and play tricks with the viewer’s eyes.

A detailed view of the golden throne of ancient Egyptian king Tutankhamun.

PHOTO: REUTERS

Married architects Roisin Heneghan and Shih-Fu Peng were tasked by the Egyptian authorities to create a structure that could house about 100,000 artefacts, as well as additional spaces for a range of uses such as research and development.

Heneghan Peng Architects was founded in 1999, and its notable projects include the Palestinian Museum in Birzeit, Palestine, which won the coveted Aga Khan Award for Architecture in 2019.

‘Remember you will die’

For more than 5,000 years, Egypt’s treasures have fired the world’s imagination, from its pyramids to the elaborate funerary imagery of solid gold sceptres, masks and coffins.

No other ancient civilisation invested so heavily in preparing for life after death, a vision that brings to mind the Latin phrase, “memento mori” or “remember you will die”.

In a culture built around the certainty of death and the promise of rebirth, pharaohs began planning their tombs almost as soon as they ascended the throne.

A full‑height glass wall in the museum frames the courtyard gardens and the Pyramids of Giza beyond.

PHOTO: IWAN BAAN

According to Washington, DC-based National Geographic magazine, the ancient Egyptians built tombs to house a pharaoh’s mummified body and belongings. This ensured his spirit could journey and live forever, with the pyramid acting as a resurrection machine and a cosmic stairway to the heavens.

Although the pyramids date back more than five millennia, the world began to understand their history only about 200 years ago.

The Grand Egyptian Museum's view of the pyramids underscores the museum’s close visual dialogue with Egypt’s ancient monuments.

PHOTO: GEORGES & SAMUEL – THE GS STUDIO

In 1822, French scholar Jean-Francois Champollion cracked the code of ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs using the Rosetta Stone – discovered in 1799 – as the vital key to the pictographic language carved into temple and tomb walls.

First, he matched the cartouches – a kind of Egyptian name tag for royalty, written in hieroglyphs – of rulers such as Ptolemy and Cleopatra to their Greek spellings. Then, drawing on his knowledge of Coptic – the later Egyptian language written in Greek letters – he realised many symbols were phonetic rather than purely pictorial. So, he built an “alphabet” of sound values that allowed him to read the Egyptian inscriptions.

His breakthrough paved the way for modern Egyptology.

A framed courtyard in the Grand Egyptian Museum offers a carefully composed view of the Pyramids of Giza.

PHOTO: GEORGES & SAMUEL – THE GS STUDIO

Longevity of the ancient Egyptians

One of the most intriguing aspects of the ancient Egyptians is that their religion and culture gradually faded away about 2,000 years ago, after Rome annexed the country in 30 BCE.

The museum shows that although the civilisation ended, its technological wonders and grandeur live on through the artefacts, says Mr Ahmed Mostafa, the Egyptian Ambassador to Singapore.

“Unlike ancient cultures such as India and China, Egypt’s pharaonic civilisation has ceased to exist,” he tells The Straits Times at the Embassy of Egypt in Eu Tong Sen Street.

“Although Egypt’s pharaonic civilisation ceased to exist 2,000 years ago, it still affects modern Egyptian culture.”

He had earlier addressed global journalists, diplomats and lovers of ancient Egyptian civilisation at The Tanglin Club on Nov 4. This was timed to coincide with the official opening of the Grand Egyptian Museum near Cairo, where 49 heads of state from around the world were hosted in a grand ceremony.

A monumental statue of Queen Hatshepsut stands in one of the museum’s main galleries.

PHOTO: GRAND EGYPTIAN MUSEUM

“What we do know from the artefacts and French scholar Champollion’s findings is that my ancestors were considerably advanced. They mastered design, architecture, mathematics, medicine and military strategy,” he said.

“They were so ahead of their time that they even kept cats and dogs as pets, and consulted veterinarians to keep their furry friends in the pink of health.”

More than a paean to the past

But it is not just a museum, Mr Ahmed points out.

The GEM Children’s Museum, spread across 5,000 sq m, is designed as a hands-on, story-driven space where children aged six to 12 years get to experience ancient Egypt by “living” it rather than just looking at exhibits.

The space is set up as a mini-world of ancient Egypt encompassing everyday life, housing, farming, religion and kingship, presented through oversized props, replicas and interactive sets.

Children can role-play driving a chariot, dining with a pharaoh, trading along the Nile or working as young scribes and doctors, as well as immerse in zones featuring music, games and sports.

The Grand Egyptian Museum’s glass pyramid feature.

PHOTO: GRAND EGYPTIAN MUSEUM

The museum campus is aimed at developing conservation science and Egyptology training through international partnerships such as collaborations with universities and foreign museums.

Its Conservation Centre houses 19 laboratories with different specialities, such as for organic materials like wood and stone, as well as wall painting, metals, textiles and mummies.

There are also climate-controlled storerooms for study collections, giving external researchers access to state-of-the-art analytical equipment and storage conditions.

Its technical capacity includes microscopy, chemical and physical analysis, 3D documentation, imaging and environmental monitoring.

This allows detailed study of objects from pre-dynastic times about 7,000 years ago to the Greco-Roman period, about 2,300 years ago.

A seated statue in one of the Grand Egyptian Museum’s Nile‑themed galleries, where artefacts are displayed against animated projections of the river that sustained ancient Egypt.

PHOTO: GEORGES & SAMUEL – THE GS STUDIO

“The Grand Egyptian Museum is home to a conservation centre, a children’s museum and research facilities. It’s conceived as a hub where the world can come together to learn more about Egyptology combining archival materials with high-tech visualisation technology such as virtual reality and augmented reality,” Mr Ahmed tells ST.

Turning a dream into reality

Dr Zahi Hawass – prominent Egyptian archaeologist, Egyptologist and Egypt’s former Secretary-General of the Supreme Council of Antiquities and former Minister of Antiquities – is overjoyed at the opening of the museum.

“Together with Farouk Hosni, I helped build this museum from the shadows of the great Giza pyramids to become the largest museum in the world with its Tutankhamun collection,” he says via messaging chat from Cairo.

Lighting effects depicting the mask of King Tutankhamun at the opening ceremony of the Grand Egyptian Museum in Giza on Nov 1.

PHOTO: AFP

Dr Zahi and former culture minister Farouk Hosni were instrumental in initiating and developing the Grand Egyptian Museum in 2002.

Dr Zahi, who was helming the antiquities council, championed the museum and secured funds to turn the dream into reality, laying the groundwork for the project and driving it forward.

“I think the reason ancient Egypt is loved by everyone around the world is because it has such a unique beauty that you cannot find in any other civilisation,” the 78-year-old tells ST. He works at archaeological sites in the Nile Delta, the Western Desert and the Upper Nile Valley.

“Masterpieces of engineering and architecture such as the Great Pyramid of Khufu and the Sphinx in the Giza plateau allow visitors a glimpse of an advanced Nile Valley civilisation. When they enter the museum and view the rich material culture found in king Tutankhamun’s intact tomb, they are in awe and speechless.”

Ms Roisin Heneghan and Mr Shih-Fu Peng are the founders of Heneghan Peng Architects.

PHOTO: HENEGHAN PENG ARCHITECTS

Speaking to ST from Dublin, the project’s architects, Ms Heneghan and Mr Peng, say that working on the Grand Egyptian Museum is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.

“Our design works to strengthen that connection to history and place, providing a home for some never-before-seen artefacts that rests upon the very land from which they were created,” says Ms Heneghan. “The result is an experience that evokes a sense of awe at the breadth and depth of ancient Egypt’s fascinating history in a way that feels both modern and timeless.”

In the vast Grand Hall of the Grand Egyptian Museum, a mirrored roof and sloping stone walls lead the eye towards daylight and a statue of Ramesses II.

PHOTO: HENEGHAN PENG ARCHITECTS

Mr Peng says the project is bigger than the sum of its parts, going beyond notions of physical size.

“It’s not just in terms of the museum. It also encompasses its landscape featuring its gardens; its context as a UNESCO World Heritage Site for its pyramids; its geology, where the fertility of the Nile meets the desert plateau; its history; its symbolism and what it means for Cairo and Egypt, as well as what it means for the world,” he adds.

Ms Heneghan says that after working on the design of the museum, she sees Egyptian history more holistically.

“I understand how the geography of Egypt was instrumental in shaping its history and therefore see the culture that arises from this place as a continuum, rather than a lost past.”

The Grand Egyptian Museum at night on the Giza Plateau.

PHOTO: GRAND EGYPTIAN MUSEUM

Visiting the museum

Go to visit-gem.com

The best time to visit is during the cooler months from September to February, when the temperature ranges from 20 to 30 deg C. The hottest months are from May to August, when the mercury can hit 40 deg C.