Life List: 10 trends to look forward to in 2026

Cities go for ‘heartware’, not just bricks-and-mortar

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

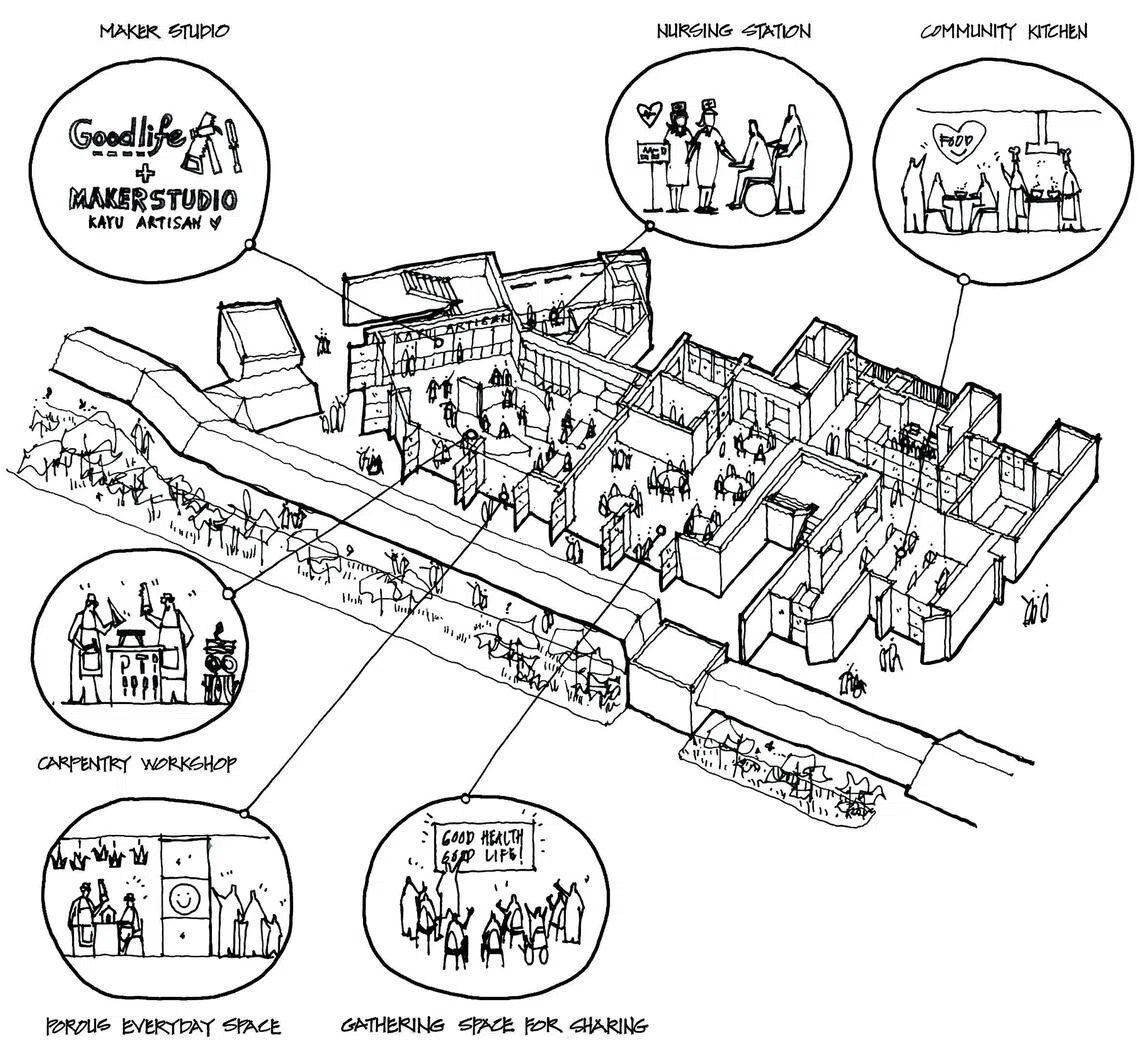

Kayu Artisan carpentry studio provides a platform for bonding and social support.

PHOTO: MONTFORT CARE

- Copenhagen's "CopenHill" values social capital in a bustling metropolis.

- Singapore shifts focus from monetising real estate to creating "social living rooms" in the hearland.

- DP Architects' "Kayu Artisan" maker space fosters community and promotes inclusivity.

AI generated

SINGAPORE – Architects around the world have experimented successfully in the last few years to reimagine urban spaces that strike a balance between monetising real estate and engaging the community meaningfully.

For instance, in Copenhagen in 2019, architects dreamt up a sloping roof for a waste incinerator building in the middle of the capital city of Denmark that pulled double duty as a year-round playground for all ages.

Urban designers from architectural practice Bjarke Ingels Group conceived the space as CopenHill, a 400m ski run, climbing wall and running path for residents, on the roof of a 41,000 sq m waste-to-energy incinerator.

By turning critical infrastructure into a civic playground, the project presented a different way of looking at the built environment – one that values social capital as much as rental yield.

In Singapore, experts also say monetising footfall may not be the only way to look at real estate in 2026 and beyond.

Stakeholders such as property owners are shifting away from transactional spaces to “social living rooms” – public engagement micro-hubs designed to reach out to residents in a neighbourhood.

Ground zero for this mindset shift is already playing out in ground-floor retail strips in the Housing Board (HDB) heartland, which used to be appraised for their dollar value per square foot. These spaces are usually rented out to beauty salons, tuition centres and small grocery stores.

Architectural firm DP Architects, founded in 1967, recently completed the design for a carpentry studio at Block 108 Bukit Purmei Road that reaches out to the community.

Maker studio as social space

Officially launched in 2024, the facility is described by the architectural firm and social service agency Montfort Care as created to reach out to male seniors, who are statistically more at risk of social isolation and less drawn to typical centre activities.

At the same time, it is part of a broader Goodlife Studio ecosystem that serves all seniors.

Montfort’s own material frames it as “a unique space where seniors – particularly men – find companionship and purpose”, which signals a targeted emphasis rather than a hard rule.

Kayu Artisan is an initiative by active ageing centre Goodlife Studio, which is run by home-grown Montfort Care, which focuses on family support, child protection and eldercare, with programmes such as Family Service Centres and active ageing centres.

In 2016, Montfort Care – a long-time DP Architects collaborator – launched community kitchen concept Goodlife Makan at the void deck of Block 52 Marine Terrace, enabling stay-alone seniors to come together to plan, cook and share meals.

The Goodlife Studio concept represents a shift away from the perception of ageing spaces as enclosed, gated or institutionalised environments.

Goodlife Studio’s specialised programmes for male seniors empower them to be active contributors of society.

PHOTO: MAZTERZ, MONTFORT CARE

Conventional senior centres are often heavily grilled or sealed behind glass, what is described as “bird cages” or “fish tanks”, notes Mr Seah Chee Huang, lead architect for Kayu Artisan, Goodlife Studio (Bukit Purmei).

“While well-intentioned, these thresholds can unintentionally reinforce separation and even stigma,” says Mr Seah, who is chief executive of DP Architects, a multi-award-winning firm with about 1,000 employees in 16 offices across 10 countries.

Kayu Artisan studio provides a fun and light-hearted maker space for people to gather.

PHOTO: MAZTERZ

The maker space fosters an environment where seniors are invited to create freely, embracing imperfection without fear of judgment.

Mr Seah says this “new model” is not a space designed for seniors, but a space with seniors belonging to the larger community, positioning them as makers, stewards and role models.

In an ageing society where there will be more HDB towns, Mr Seah says this approach offers a scalable and sustainable blueprint for more inclusive, flexible and socially connective community infrastructure.

“On one level, the Malay word ‘kayu’ refers to materiality, where wood becomes the foundation of the studio – warm, tactile and natural, setting a comforting tone,” he says.

“But more importantly, the colloquial meaning of ‘kayu’ – meaning clumsy or awkward – is reframed. When paired with ‘artisan’, it challenges assumptions around ability, dignity and usefulness. The studio is designed to lower psychological barriers and celebrate participation over perfection, focusing on the joy of making, learning and social connection.”

The maker space creates an environment where seniors are invited to create freely, embracing imperfection without fear of judgment.

PHOTO: MAZTERZ

The hands-on nature of woodworking in a studio with glass walls that piques the interest of passers-by is intentionally aimed at male seniors, whose social networks often diminish significantly after their retirement.

Mr Seah says this is not only a trend, but also an essential and growing shift. In dense cities like Singapore, void decks and neighbourhood spaces can become platforms for connection rather than consumption.

“We foresee HDB towns increasingly supported by a richer mix of transactional and non-transactional spaces, cafes alongside community kitchens, shops alongside maker studios, with more public, private and people partnership,” Mr Seah adds.

“In an ageing society, such spaces will be critical in shifting from a model of dependency to one of collaborative stewardship, dignity and shared responsibility.”

Through purposeful design and creative programming, people can reshape their environment and offer another lens through which to see others and themselves.

PHOTO: DP ARCHITECTS

Mr Rene Tan, co-founder of local practice RT+Q Architects, agrees, adding that HDB void decks and even HDB commercial shophouse units can serve as part of the “heartware” that binds a community together in housing estates.

Changing face of urbanism in 2026

“The future of urbanism is getting so complex, and one cannot rely on ideas that normally characterise urbanism any more. Traditional ideas like large open spaces as urban living-rooms should be rethought, especially in Singapore, where the weather is so severe,” says Mr Tan. He was the festival director of Singapore Archifest 2025, the country’s largest annual architecture festival.

“HDB’s void deck infrastructure is so well done and, thinking ahead, void decks may become the new and future urban ‘piazza’ in tropical urban settings like Singapore. A great variety of street-life activities can add further to an already vibrant urban culture.”

Using the element of “fun,” three distinct programmes were conceptualised for three different studio settings, each forming a facet of a social living room.

PHOTO: DP ARCHITECTS