Asian Insider

Behind the fall and rise of India's coronavirus cases

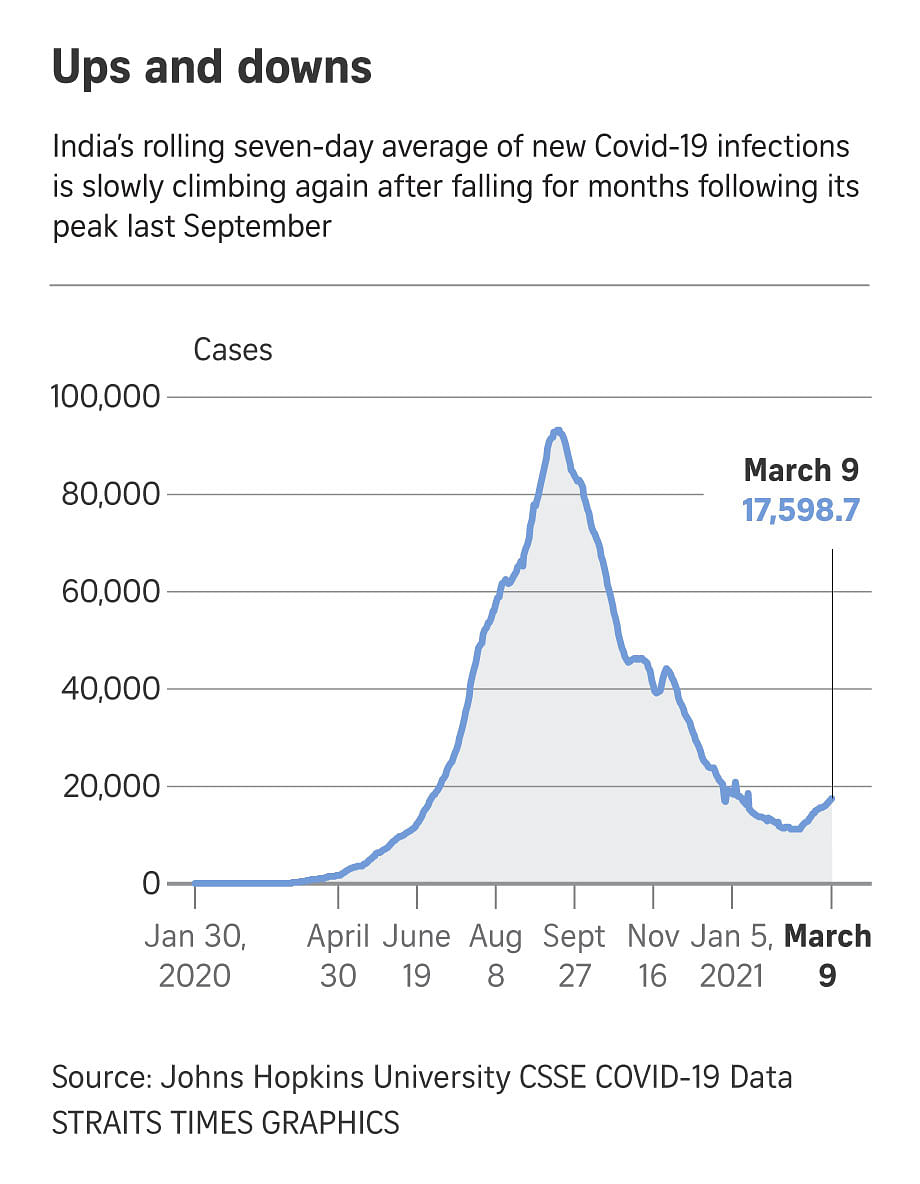

India had one of the highest Covid-19 cases last year but low fatality rates. Daily infections plunged late last year but are climbing again. The Straits Times explores the issue.

Sign up now: Get insights on Asia's fast-moving developments

Senior citizens sit in an observation room after being inoculated with a Covid-19 vaccine at a government hospital in Bangalore, on March 5, 2021.

PHOTO: AFP

NEW DELHI/BANGALORE - It was in September last year that India overtook Brazil to emerge as the second worst-hit country by the Covid-19 pandemic. The country even seemed poised to overtake the US in November, but infections began plummeting mysteriously to around 10,000 cases a day.

Today, infections are surging again, but even at the height of the pandemic, Covid-19 was less severe for Indians. Most showed mild symptoms, and compared with other countries, relatively few infected patients died. India has just about 115 deaths per million, while the US reports 14 times more deaths at 1,600 per million.

Experts have been studying data closely to understand Indian immunity and the character of the coronavirus here, in the hope that it can help other countries bolster their defences.

Hygiene hypothesis

Dr Vineeta Bal, an immunologist and visiting faculty member at the Indian Institute of Science Education and Research in Pune, said one possible reason for the less severe nature of Covid-19 in India could be that its population was already exposed to many pathogens, which she described as "common cough-and-cold kind of coronaviruses".

This is the hygiene hypothesis, according to which people in densely populated countries with low sanitation standards get exposed to multiple pathogens at an early age. This trains their immunity to ward off diseases later in life.

But this is only speculation, Dr Bal noted, given the absence of data on the prevalence of previous coronavirus infections in India. "So did we have it (cross-immunity) to the extent that there might have been some protection that was offered? As an immunologist, I can say it is a possibility but do I have proof for it? No."

Moreover, not all countries with socioeconomic and health conditions similar to India had the same experience.

Professor Gautam Menon, Delhi-based Ashoka University's a physics and biology expert who models infectious diseases, said: "It is hard to see what prior exposure might protect Indians specifically, but not, say, Brazilians or Mexicans, given that viruses and bacteria don't respect national boundaries and our climatic conditions are not very dissimilar."

Epidemiological estimates also suggest that deaths may be undercounted, and that the true numbers could be two to five times more.

"If you compute fatalities in urban regions of India, rather than looking at pan-Indian numbers, accounting for such undercounting, the numbers are not too far from the Covid-19 fatality rates reported from elsewhere," added Prof Menon.

Youth and genes

Younger age is the second likely factor lowering the death rate. As the disease kills far fewer young people, India's youth, with people under the age of 25 years constituting nearly 47 per cent of the population, may have been an asset.

India's lower obesity rates, considered a major risk factor for Covid-19, could have also lowered mortality. Furthermore, a study by Indian researchers published last month suggested that the deficiency of a lung-protecting protein in the Caucasian population may have made them more susceptible to the spread of a coronavirus variant when compared to those in Asia.

The country's youthfulness has impacted the severity of symptoms too. When the health ministry analysed state-level infection data in Aug 2020, it found that 80 per cent of Covid patients in India were asymptomatic. More than two-thirds of those under 50 can be expected to not show Covid symptoms at all or only transiently, at best, said Prof Menon.

Other hypotheses attributed Indians' immunity and lower fatality to much of the population having received BCG vaccinations against tuberculosis, having higher vitamin D levels, and the hospitals here having initially used chloroquine to treat Covid patients. Some even claimed the hotter temperature prevented transmission.

None of these were proven conclusively, but contributed to "a dangerous belief" among Indians that they had "superior genetic immunity" and had also attained herd immunity, warned Dr Samiran Panda, head of epidemiology and communicable diseases at the Indian Council of Medical Research.

The country's third serological survey released last month found that just about one in five Indians had been infected with the coronavirus and developed antibodies. This ruled out any herd immunity, as it means more than 75 per cent of Indians remain vulnerable to infection.

Regional differences also reveal more complexities. The disease has been more prevalent in urban India, with the recent increase being reported mainly from cities with higher and denser population pockets. Locals in rural areas, on the other hand, spend more time outdoors and live in well-ventilated dwellings, which could help explain why there has been less transmission.

Fresh spikes

But now, new Covid-19 infections in India are on the rise, reaching more than 17,900 on Tuesday (March 9), taking the number of cases in India to over 11.26 million. After five months of an astonishing decline in the rate of infections, India's seven-day rolling average has risen consistently since Feb 14.

Nearly all experts attribute the increase, to some extent, to the gradual opening up of schools, offices and public transport since November, accompanied by a general weariness with restrictions.

"The real surprise to me and others is that this (rise) didn't happen earlier, especially around the festival season in North India across November," said Prof Menon.

For Dr Bhramar Mukherjee, the chair of Biostatistics at the University of Michigan, who has been tracking the pandemic's evolution in India, the increase throws up a key question: Are people getting re-infected by the coronavirus?

Fresh spikes have been reported mainly from urban areas, including in Delhi and Pune, where over half the population was reported to have antibodies. If one believed that people with antibodies cannot get re-infected, another huge spike in these areas is "almost nearly impossible", said Dr Mukherjee.

"But if you believe that re-infections are starting and the disease-induced immunity is waning, then all bets are off. You can see a huge peak," she added. "So I am really torn between these two choices because there is no data from India which says these are reinfections."

New strains

Scientists are also studying the role of new coronavirus strains and their potential role in causing outbreaks, including through reinfections. Studies suggest a new variant known as P.1 may have led to reinfections and a new outbreak earlier this year in Manaus, Brazil, where 76 per cent people had already been infected by October last year.

India has detected about 240 new cases of the Brazilian, UK and South African strains of the coronavirus.

Dr Bal said India had not done enough sequencing of the virus to predict that it "may not be more virulent or more lethal".

In December, the government launched a consortium of 10 research institutions to track the virus' new variants and their potential public health impact.

Dr Rakesh Kumar Mishra, director of the Hyderabad-based Centre for Cellular & Molecular Biology, one of the consortium's participating institutions, said research so far has indicated no correlation between the recent increase and any new virus strain. Instead, he blamed slackening public Covid-related behaviour.

A more definite answer may come once adequate samples collected from states seeing an uptick in new infections are sequenced and analysed.

Confirmed re-infections in India are few and the spread of imported strains remains limited to foreign travellers and their primary contacts. But the threat of a new strain capable of beating the immune system looms large.

"To me the biggest source of threat of a new variant is from internal sources, not abroad," said Dr Mishra, "because we have one of the largest numbers of active cases."

This means the next nasty coronavirus variant could emerge from this pool in the country and spread wider, causing infections with more severe symptoms and mortality. "New variants, some exclusive to India, may simply transmit better among people," added Prof Menon.

Vaccination

A rapid pace of vaccination is crucial to immunise a majority of Indians before the virus attains a more lethal form. While the number of jabs has increased in recent days as senior citizens sign up, initial progress when the drive launched on Jan 16 was held back by tech glitches and vaccine hesitancy among healthcare workers.

Given India's slow start, Dr Mukherjee said the country cannot afford any further delays. "India's opportunity was handed over on a beautiful plate for it to roll out its vaccine widely when the case count was down," she told The Straits Times. "That would really have sealed the deal but it did not happen."

Dr Mukherjee is still hopeful that India will ramp up its vaccination roll-out to enlarge the shield of vaccine-induced immunity before disease-induced immunity wanes and leads to a new surge, including through reinfections caused by newer strains.

Until India gets to such a sweet spot, Indians must continue practising all recommended Covid-appropriate behaviour. Everybody is still vulnerable and a potential source, said Dr Mishra. "If we drop our guard, we are running a big risk and the next peak or lockdown is not affordable."