Afghan military was built over 20 years. How did it collapse so quickly?

Sign up now: Get insights on Asia's fast-moving developments

A 2016 photo shows US soldiers overseeing training of their Afghan counterparts in Afghanistan's Helmand province.

PHOTO: NYTIMES

KANDAHAR (NYTIMES) - The surrenders seem to be happening as fast as the Taleban can travel.

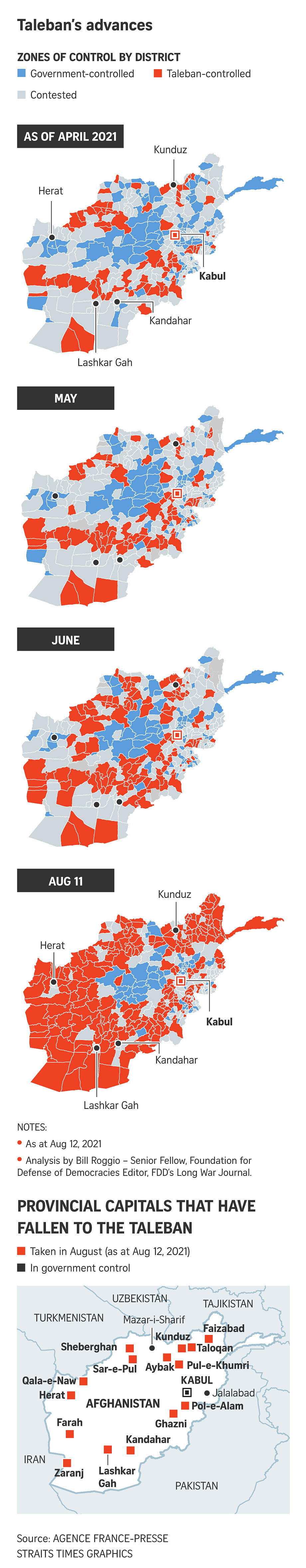

In the past several days, Afghan security forces have collapsed in more than 15 cities under the pressure of a Taleban advance that began in May. On Friday (Aug 13), officials confirmed that those included two of the country's most important provincial capitals: Kandahar and Herat.

The swift offensive has resulted in mass surrenders, captured helicopters and millions of dollars of US-supplied equipment paraded by the Taleban on grainy cellphone videos. In some cities, heavy fighting had been under way for weeks on their outskirts, but the Taleban ultimately overtook their defensive lines and then walked in with little or no resistance.

This implosion comes despite the United States having poured more than US$83 billion (S$112 billion) in weapons, equipment and training into the country's security forces over two decades.

Building the Afghan security apparatus was one of the key parts of the Obama administration's strategy as it sought to find a way to hand over security and leave nearly a decade ago. These efforts produced an army modelled in the image of the US military, an Afghan institution that was supposed to outlast the American war.

But it will likely be gone before the US is.

While the future of Afghanistan seems more and more uncertain, one thing is becoming exceedingly clear: The US' 20-year endeavour to rebuild Afghanistan's military into a robust and independent fighting force has failed, and that failure is now playing out in real time as the country slips into Taleban control.

How the Afghan military came to disintegrate first became apparent not last week but months ago, in an accumulation of losses that started even before President Joe Biden's announcement that the US would withdraw by Sept 11.

It began with individual outposts in rural areas where starving and ammunition-depleted soldiers and police units were surrounded by Taleban fighters and promised safe passage if they surrendered and left behind their equipment, slowly giving the insurgents more and more control of roads, then entire districts.

As positions collapsed, the complaint was almost always the same: There was no air support or they had run out of supplies and food.

But even before that, the systemic weaknesses of the Afghan security forces - which on paper numbered somewhere around 300,000 people but in recent days have totalled around just one-sixth of that, according to US officials - were apparent.

These shortfalls can be traced to numerous issues that sprung from the West's insistence on building a fully modern military with all the logistical and supply complexities one requires, and which has proved unsustainable without the US and its Nato allies.

Soldiers and policemen have expressed ever-deeper resentment of the Afghan leadership. Officials often turned a blind eye to what was happening, knowing full well that the Afghan forces' real manpower count was far lower than what was on the books, skewed by corruption and secrecy that they quietly accepted.

And when the Taleban started building momentum after the US' announcement of withdrawal, it only increased the belief that fighting in the security forces - fighting for President Ashraf Ghani's government - wasn't worth dying for. In interview after interview, soldiers and police officers described moments of despair and feelings of abandonment.

On one front line in the southern Afghan city of Kandahar last week, the Afghan security forces' seeming inability to fend off the Taleban's devastating offensive came down to potatoes.

After weeks of fighting, one cardboard box full of slimy potatoes was supposed to pass as a police unit's daily rations. They hadn't received anything other than spuds in various forms in several days, and their hunger and fatigue were wearing them down.

"These french fries are not going to hold these front lines!" a police officer yelled, disgusted by the lack of support they were receiving in the country's second-largest city.

By Thursday, this front line collapsed, and Kandahar was in Taleban control by the next morning.

Afghan troops were then consolidated to defend Afghanistan's 34 provincial capitals in recent weeks as the Taleban pivoted from attacking rural areas to targeting cities. But that strategy proved futile as the insurgent fighters overran city after city, capturing around half of Afghanistan's provincial capitals in a week, and encircling Kabul.

"They're just trying to finish us off," said Abdulhai, 45, a police chief who was holding Kandahar's northern front line last week.

The Afghan security forces have suffered well over 60,000 deaths since 2001. But Abdulhai was not talking about the Taleban, but rather his own government, which he believed was so inept that it had to be part of a broader plan to cede territory to the Taleban.

The months of defeats all seemed to culminate on Wednesday when the entire headquarters of an Afghan army corps - the 217th - fell to the Taleban at the airport of the northern city of Kunduz. The insurgents captured a defunct helicopter gunship. Images of a US-supplied drone seized by the Taleban circulated on the Internet along with images of rows of armored vehicles.

<p>Taliban fighters stand over a damaged police vehicle along the roadside in Kandahar on August 13, 2021. (Photo by - / AFP)</p>

PHOTO: AFP

Brigadier General Abbas Tawakoli, commander of the 217th Afghan Army corps, who was in a nearby province when his base fell, echoed Abdulhai's sentiments as reasons for his troops' defeat on the battlefield.

What remains of the elite commando forces, who are used to hold what ground is still under government control, are shuttled from one province to the next, with no clear objective and very little sleep.

The ethnically aligned militia groups that have risen to prominence as forces capable of reinforcing government lines also have nearly all been overrun.

The second city to fall this week was Sheberghan in Afghanistan's north, a capital that was supposed to be defended by a formidable force under the command of Marshal Abdul Rashid Dostum, an infamous warlord and a former Afghan vice -president who has survived the past 40 years of war by cutting deals and switching sides.

On Friday, prominent Afghan warlord Mohammad Ismail Khan, a former governor, who had resisted Taleban attacks in western Afghanistan for weeks and rallied many to his cause to push back the insurgent offensive, surrendered to the insurgents.

"We are drowning in corruption," said Mr Abdul Haleem, 38, a police officer on the Kandahar front line earlier this month. His special operations unit was at half strength - 15 out of 30 people - and several of his comrades who remained on the front were there because their villages had been captured.

"How are we supposed to defeat the Taleban with this amount of ammunition?" he said. The heavy machine gun, for which his unit had very few bullets, broke later that night.

As of Thursday, it was unclear if Mr Haleem was still alive and what remained of his comrades.